Received 26 April 2019; Revised 1 December2019, 7 December 2019, 4 February 2020; Accepted 12 March 2020.

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Çiğdem Sıcakyüz, Ph.D., Çukurova University, Engineering Faculty, Industrial Engineering Department, Balcalı 01330 Sarıçam, Adana, Turkey, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., tel. +90(322)3386084/2074  , corresponding author.

, corresponding author.

Oya Hacire Yüregir, Associate Professor, Çukurova University, Engineering Faculty, Industrial Engineering Department, Balcalı 01330 Sarıçam, Adana, Turkey, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., tel. +90(322)3386084/2074

Abstract

Although information systems provide many benefits to the organization, many organizations are experiencing difficulties with the process of change. Resistance to change is one of the most considerable challenges in this phase. This study aimed to investigate the causes of resistance by healthcare personnel to IT in Adana Numune Hastanesi, which is a state-run hospital located in Adana, Turkey. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) was expanded by adding factors such as affective commitment, gender, and age. Logistic regression analysis was carried out on the research model through 291 collected survey data using SPSS (version 21). The overall percentage accuracy prediction was 55.3% for parameters of the initial model and 80.8% for the stepwise model after the third step. According to the results, while the factors “perceived usefulness of IT,” “perceived ease of use of IT,” and “affective commitment” were found to have an influence on the resistance of use of IT, demographic factors such as age, gender, position, and tenure were not related. Managers should create an environment for increasing staff commitment by including them in decision-making and process changing. Thus, not only could the manager use the organizations’ resources productively, but also future change projects could be carried out effectively, roughly, and timely. Therefore, through its committed personnel, the hospital could sustainably compete with its competitors in the market and make more profit.

Keywords: healthcare information systems, organizational affective commitment, resistance to innovation, change management, Technology Acceptance Model, TAM, Markus’s Model

INTRODUCTION

With the rapid development of technology, organizations are buying new technologies in order to gain competitive advantage over their rivals. Recently, information technology (IT) is gaining grounds in healthcare. The leading information technologies used in health systems are Hospital Information Technology (HIT), Electronic Patient Record (EMR), Clinical Decision Support (CDS), e-Health and RFID technology, and Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE) system. These systems have the potential to improve the health of individuals by providing improved quality and minimizing cost. For example, EMR systems allow processes such as displaying, editing, and recording patient graphs on the computer. These systems provide quick access to patient information by providing a digital information area for physician notes (Walter & Lopez, 2008) and facilitate administrative work by providing e-mail access; control through the internet and clinical decision support (Van Slyke et al., 2007).

Although technology offers organizations many advantages, the use of IT in hospitals remains low in the USA (Buntin et al. 2011; Van Slyke et al. 2007). The reasons for failure in change projects can be multifarious, such as organizational, individual, or technological. The individual-based reasons can range from the personnel’s lack of motivation for change (Bertolini et al., 2011)in which scheduled and unscheduled operations often have to coexist and be managed, ways to minimise patient inconvenience need to be studied. A framework based on event-driven process chains (EPCs to resistance of the end-user to technology (Bhattacherjee & Hikmet, 2007; Meissonier & Houzé, 2010)we conceptualise a whole theoretic-system we call IT Conflict-Resistance Theory (IT-CRT. Such lack of communication in the team or incompetent management (Hadjimanolis, 2003) can be thought of as organizational reasons, whereas the complexity and difficulty of technology are regarded as technological reasons (Rogers et al., 2019).

According to Barutçugil (2013), the output of resistance to IT did not only result in non-use but also led to work-related accidents, an increase in compensation claims, increased absenteeism, sabotage, an increase in expenditure due to health and falling productivity. Moreover, an unsuccessful transition process of a purchased innovation in the organization brings costs to the organizations.

The main aim of this study was to determine whether affective commitment and demographic factors, as external factors, have an impact on the resistance to IT in the healthcare sector in Adana, Turkey. The sub-objective of this study was to shed light on managers by assessing their personnel’s underlying attitudes and behaviors regarding the emotional aspect of IT projects. This will ensure maximum utilization of existing resources (people, money, time, and machine) through the right productive strategies so that they can compete and increase their profit. In this context, the following research questions were examined.

RQ1: Is there any relationship between resistance and the organizational

affective commitment of healthcare personnel to the resistance they

display on the use of hospital information systems in Adana, Turkey?

RQ2: Is there any relationship between resistance and the demographic

factors such as age, gender, tenure, and position of the healthcare

personnel to the resistance they display on the use of hospital information

systems in Adana, Turkey?

RQ3: Is there any relationship between resistance and perceived usefulness

and perceived ease of use of the hospital information systems to the

resistance they display on the use of hospital information systems in

Adana, Turkey?

This study gives different perspectives of non-use of IT from the literature. In the literature, most of the studies were based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) by Davis (1989), in which the perceived ease of use and usefulness of new technologies have been demonstrated as the main factors in their acceptance, to predict the intention of employees towards the use of IT rather than resistance to technology.

The literature on resistance to change is very rich. There are studies emphasizing that the psychological dimension, as well as the technical dimension of change, are important in managing the change in the process of applying technology. Sıcakyüz and Yüregir (2018) asserted that reasons such as fear of authority and job loss, lack of IT interest, lack of management and technical support, complexity of IT, and unreadiness for change can play roles in technology adoption. The human-based resistance such as personality, emotions, talents should not be ignored since there are many studies that have found that feelings and individual differences affected the acceptance of change (Mdletye et al., 2014; Vishwanath Venkatesh & Morris, 2000)which forms part of the human dimension of transformational change. This paper presents empirical evidence gathered from the Correctional Centres of the South African Department of Correctional Services in the Province of KwaZulu-Natal on resistance-to-change behavior displayed by the employees of Correctional Services, namely Correctional Officials regarding the fundamental culture change from the punishment-oriented philosophy to the rehabilitation-driven philosophy in terms of the treatment of sentenced offenders (herein referred to as DCS change.

There are also researchers who argue that the attitude of employees should be considered as a critical success factor in managing the change process of the organization (Foster & Wilson-Evered, 2006). Since other studies have pointed out that user resistance is the second most important factor costing time and money (Ali et al., 2016). One reason for workers’ resistance could stem from a weakness of commitment to their organization. (Laumer, 2012)process characteristics, technology characteristics, and characteristics of the change process. Moreover, it can be shown that user resistance is not only related to the observed usage behavior, but also in work- and process-related consequences. The results contribute not only to IT adoption and change management literature, but also to the literature on Human Resources Information Systems (HRIS pointed to the resistance of employees to a new system implementation at a financial services provider. Consequently, this can decrease both organizational commitment of employees and overall job satisfaction but can increase turnover intention. Thus, affective commitment can be seen as a critical factor in accepting or implementing technology or change in the organization. It can be a consequence of the resistance of employees, or it can be a reason why employees resist a new system.

To predict resistance, it is necessary to understand why there is resistance to technology, rather than investigating why it is not adopted (Ram & Sheth, 1989). Although there is some research about the resistance model, a valid and adaptable model has not yet been found (Samhan & Joshi, 2015). Moreover, some researchers have pointed out the psychological reasons for non-acceptance of technology (Ram & Sheth, 1989). Still, no research has been found on the impact of the affective commitment of an organization’s employees on the resistance to change and/or technology in the process of organizational change. Due to investigation of the impact of both the main factors of TAM and the affective commitment of personnel on the resistance to IT, the study differs from the other researches in the literature.

Not only is this study going to show the effects of TAM’s main variables on the resistance of personnel to use IT, but also pave the way for more attention on the strong impact and importance of emotion and the relationship of the personnel to their organization on the resistance to organizational change in the near future. Another contribution of this study is that it will give some practical insights to managers on the steps they can take to prevent emerging resistance. Furthermore, it will enable managers to use their organizations’ resources productively so that future change projects can be carried out effectively, smoothly, and timely. Therefore, through its committed personnel, the hospital can sustainably compete with its competitors in the market and make more profit.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Organizational development and change management

Organizational development (OD) has been around since the early 1930s (Worren et al., 1999). Indeed, organizational development dates back to Fredrick Taylor, who reformed it into the productivity of work shortening time and arranging motion in the workplace. His focus on the elimination of inefficient work, and guidance to managers on how to organize tasks and manage workers, was a standard for most managers (Lewis et al., 2016). This mechanistic view of an organization, although it leads to the best people being employed and an optimum way to manage work and employees in order to make more profit, changed at the time of Kurt Lewin, whose work is prevalent in the field of sociology and psychology. Al-haddad and Kotnour (2015) expressed that most researchers had been under Lewis’s influence. Probably, for this reason, organizational development and organizational learning are often seen as having the same meaning (Rothwell et al., 2010).

In the literature, organizational learning has been given more importance because it is understood that humans are the most essential factor in the driving wheel of the organization. That is why, to compete in the market and work efficiently, several techniques were developed, namely Continuous Improvement (CI), Business Process Redesign (BPR), Total Quality Management (TQM), and Balanced Scored card (BSC) (Paton & McCalman, 2008). The performances of organizations were different, even though they were using the same methodology or technology because technology alone could not perform everything (Powell & Dent-Micallef, 1997). They needed to have both contemporary technology and the knowledge of management techniques, as well as a leadership style to protect the existence of the organization. Due to the complexity of external organizational factors like government policy, globalization, rapidly changing technology or unclear, extra and various consumer demands, organizations had to keep developing themselves and introducing more radical changes than classical organizational development. As such, many definitions of organizational development can be seen in the literature. For example, Anderson and Anderson (2010) have defined it in three ways according to the intense and technical level of change such as developmental, transitional and transformational, while Al-Haddad and Kotnour (2015) have pointed out that organizational development is related to change management in the social research field.

Furthermore, Worren et al. (1999) have defined change management as a new and different field rather than an extension of classical organizational development because it requires a range of activities such as employee performance, process consulting, business restructuring, strategic human resource management, information technologies and many more. Thus, the classical manager could not deal with these complexities, so organizations required special managers called change agents to manage the change processes. Nevertheless, this was not enough for successful change implementation, and about 70% of change projects failed, according to Beer and Nohria (2000).

Some authors have developed strategies to carry out change projects (Kotter & Schlesinger, 2008), whereas others have investigated the causes of failing projects. The reasons found differ, such as the size and hierarchy of the organizations (Frambach & Schillewaert, 2002), management approach (Hadjimanolis, 2003; Keen, 1981), unreadiness of personnel (Armenakis et al., 1993; Jones et al., 2005), personality (Oreg, 2007), open communication and agreement with personnel (Powell & Dent-Micallef, 1997), and the personnel’s lack of motivation for change (Bertolini et al., 2011)in which scheduled and unscheduled operations often have to coexist and be managed, ways to minimise patient inconvenience need to be studied. A framework based on event-driven process chains (EPCs. Others claim that the resistance of employees, customers, suppliers, partners and decision-makers (Oreg, 2003; Zwick, 2002) shown towards change was a barrier, preventing the successful implementation of innovation (Nisbet & Collins, 1978), and that this resistance can arise from different factors such as the difficulty and complexity of innovation (Rogers et al., 2019).

Furthermore, Markus (1983) stated that people are resistant to change both for new system-based reasons as well as the interaction of the characteristics between people and the new system. Besides, Markus (1983) defined the interaction as a perspective in which people perceive that new technology will alter their current social and job structure, and power relations.

Ali et al. (2016) categorized six interaction-based user resistances in their literature review. These resistances were the interaction of system-based and human-based characteristics (Markus, 1983), increased access to the data but lesser autonomy (DeSanctis & Courtney, 1983; Jiang et al., 2000; Joshi, 1991; Krovi, 1993; Lapointe & Rivard, 2005)implementation research suggests that it is not enough that the technology be friendly to the user. The user must also be friendly to the system. In formulating solutions to implementation problems, the field of organization development (OD Lapointe & Rivard, 2005;we used a multilevel, longitudinal approach. We first assessed extant models of resistance to IT. Using semantic analysis, we identified five basic components of resistance: behaviors, object, subject, threats, and initial conditions. We further examined extant models to (1 2007), psychological contract and new technology (Klaus & Blanton, 2010), a lack of organizational fit (Meissonier & Houzé, 2010)we conceptualise a whole theoretic-system we call IT Conflict-Resistance Theory (IT-CRT, social influence (Eckhardt et al., 2009), and uncertainty (Jiang et al., 2000; Waddell & Sohal, 1998). The relationship between employee and management, the experiences and tenure of the employee in the workplace could also affect the adoption of technology by employees. Eckhardt et al. (2009) induced that social influence from workplace experiences has a significant impact on IT adoption (Ali et al., 2016).

True management as an enabler to success in the change process

In a related study, it was reported that the emotional reactions of managers to change had an impact on their work attitudes. The more positive the manager’s approach to work was, the higher the turnover they made, compared to managers whose approach to their work was negative (Mossholder et al., 2000). This shows that it is mandatory that managers adopt change processes before gaining employment. The right person to lead change projects ranges from organization to organization.

Although change agents could be from either outside or inside an organization (Paton & McCalman, 2008; Rothwell et al., 2010), external change agents are paid more than internal ones and are responsible for only the current change project (Paton & McCalman, 2008), which often allows organizations to seek a new change agent for each project. Due to the easy access of information, the internal change agent has advantages over an external agent.

Moreover, Winklhofer (2002) emphasized that it is necessary for project managers to be aware of minor organizational events and cope with them by acting efficiently. Because of their technical, interdisciplinary, and integrative business skills (Lannes, 2001), managers can act as change agents. In addition, their competences in interpersonal communication, integrating marketing and economics, as well as the management of engineering (Duimering et al., 2013), make it possible for managers to identify the gaps between the disciplines and choose the right strategies for problem-solving. Their responsibilities for the project’s topics, such as determining actual projects, defining clear project goals, building teams, managing time, and stopping the project (Spurgeon, 1997), give managers a broad scope. Furthermore, their knowledge about products, processes, and the personnel who are responsible for business processes in the organization (Baker, 2009), may facilitate enhanced operation and control over change projects. Therefore, managers could play an important role in the change process by committing the personnel and themselves to change, hence paving the way for sustainable success in future change projects.

Commitment as an enabler to success in change process

The previously mentioned reasons for the reactions of personnel to change can stem from beliefs, a lack of interest to change, misunderstanding, and a lack of trust. Indeed, Schalk, Campbell, and Freese (1998) believe that psychological agreement is mandatory to deal with their resistance to change. For example, in Japan, those who migrate through change processes are models of inspiration because their personnel integrates to adapt their goals. The reason for their success is the commitment of the employee to the organization (Bakan, 2011).

Moreover, in the King Faisal Hospital in Al-Taif Governorate (KSA), it was reported that organizational commitment played an important role in the employees’ acceptance of changes. The more committed the personnel were to their organization, the more they wanted to participate in a change project (Nafei, 2014). Organizational commitment is related to the emotional conditions of the person in that organization. For example, an employee who is satisfied with the organization acts with a sense of commitment to the purpose and values of the organization and, as a result, the quality of the work experience is observed to be positive (Cook & Wall 1980). Mowday et al. (1979) are the most renowned researchers on this topic. According to them, those with organizational commitment have a strong belief in accepting the aims and values of the organization. They are also eager to demonstrate the effort required for the organization and are very willing to stay in the organization (Mowday et al., 1979). It is expected that those who are committed to the organization will, therefore, act accordingly to the organization's aims and will not immediately reject any innovation that will benefit the organization. In an organization where the personnel has a lower commitment, it could lead to failure due to poor work outputs. For example, absenteeism, lateness and resigning are some of the actions of personnel who have a lower commitment to their firms (Morris & Steers, 1980). Controversially, affective commitment and normative commitment has an impact on readiness of change, personal and organizational valence (Visagie & Steyn, 2011).

Theoretical model and hypotheses

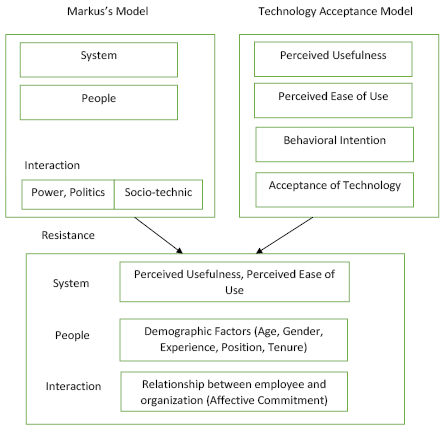

This research model is based on the mixed model of the study of Markus (1983) and a modified TAM. Markus analyzed the resistance factors in three contexts as human, system, and interaction of system and human. According to Markus (1983), employees can fear that new systems will change their status, such as losing authority. The perception of people can be different due to their characteristics or social status in the workplace. The features of a new system can be determinative of the perception of people. Therefore, the perceived usefulness and ease of use of IT were considered as an interaction of human and system.

In this study, affective commitment, as an indicator of the level of the relationship between people and organization, was assumed to examine the interaction between human and system factors mentioned in the model of Markus. In the following section, it can be seen that committed people have a positive relation to the organization and can accept change when they are involved in the implementation of change, as Markus (1983) pointed out. It is expected that the more committed employees are to their organization, the less resistant they are to the new technology or system.

Laumer & Eckhardt (2010) stated that resisting a new system lessens employees’ commitment to their organization. Although the authors consider this factor to be a result of the resistance of employees to a new system or technology, affective commitment can also be the reason for resistance since affectiveness could be a good indication of organizational performance, as concluded by Authayarat and Umemuro (2012). Thus, in this study, affective commitment was seen as an interaction between people and organization, and as an external variable of TAM. The other external variables were chosen from the demographic factors which Joia, Gradvohl De Macêdo, and Gaete De Oliveira (2014)by reviewing the extant literature with respect to resistance behavior to information systems, a theoretical model containing the factors that influence user resistance behavior to enterprise systems was compiled. Then, via a web survey, 169 valid questionnaires filled out by Brazilian IT managers who had already implemented enterprise resource planning (ERP suggested in their studies. The conceptual model of the research is shown in Figure 1.

As a mixed model of Markus’s model (1983) and TAM, this study researched whether the relationship between personnel and management in addition to system properties (as usefulness and ease of use of system) and personal characteristics such as gender, age, working years and position affect the user resistance to information technology or not.

Perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use

The variables of TAM are utilized in this study. The hypotheses are explained below and their theoretical justification in order to set and analyze the research model. The most pervasive employed model of the adaption of technology is TAM (Davis et al., 1989; Vishwanath Venkatesh & Morris, 2000; Viswanath Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). There are three main constructs in TAM.

Figure 1. Conceptual model

These are ‘perceived usefulness’ (PU) and ‘perceived ease of use’ (PEU), which describe the beliefs related to IT by the end-users, and acceptance of technology (TA), which indicates that the users have an intention to use the technology. PU stands for the belief that using IT results in efficient job performance, and PEU stands for using IT without any effort. According to TAM, users should see the benefits of technology and use it easily before they accept it.

Past studies have expanded TAM by adding the external variables to the main variables PU, PEU, and BI (behavior intention). The external variables are individual differences and demographic properties (ages, gender, etc.), system characteristics, social efficiency, and facilitating conditions (Viswanath Venkatesh & Bala, 2008). Furthermore, in the study of Venkatesh and Bala (2008), they mentioned that PEU belief worked in the beginning phase and post-implementation phase of the technology. In the beginning phase of the technology, they added factors such as computer self influence, computer anxiety, computer playfulness, and perceptions of external control. In the post implementation phase, perceived enjoyment, objective usability, and efficiency especially were added in order to increase the interaction with the technology. The other expanded model, called TAM2, in which the variables experienced and voluntariness were mediated in, was suggested by the study of Viswanath Venkatesh and Davis (2000) and this model was also composed of subjective norms, image, job relevance, output quality, resulting in demonstrability variables apart from TAM. Afterward, TAM was integrated with TAM2 and so emerged TAM3 (Viswanath Venkatesh & Davis, 2000), UTAUT (Davis, 1989). All the extended models are related to TAM. However, in this study, perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEU) were used to predict resistance to hospital information systems. Thus, the hypotheses related to PU and PEU beliefs are:

H1: The perceived usefulness (PU) of the hospital information system has no effect on the resistance of hospital personnel to the hospital information system (IT).

H2: The perceived ease of use (PEU) of the hospital information system has no effect on the resistance of hospital personnel to the hospital information system (IT).

Affective commitment of personnel to organization

Unlike technological reasons, the emotions and affective reactions of personnel and events within the organization have effects on the acceptance and use of IT (Stam & Stanton, 2010). It is reported that facilitating factors such as perceived organizational supports affect the acceptance of change or use of IT (Taylor & Todd, 1995; Vishwanath Venkatesh & Morris, 2000). The potential adopters of technology have willingly accepted the change or technology and have not felt any obligation to the acceptance of it. Hence, the voluntariness variable was used as mediated. This variable is related to willingness only in terms of the feature of technology. As mentioned above, the positive relations of personnel with their organizations have led to positive attitudes and behaviors, and better work output, even if they do not want to act towards change. These efforts given by the personnel are because of their commitment to the organization.

Hence, in this study, we have concentrated on the relationship between organizational commitment and resistance to change in IT usage in the healthcare industry. While there are many types of research on resistance to change, no records on organizational commitment were found in the literature in this context. This research tries to underscore the importance of this factor in order to benefit IT at a maximum level. Based on the literature reviewed, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: There is no relationship between the hospital personnel’s affective commitment to the organization and their resistance to the hospital information system (IT).

Demographic factors

Demographic factors such as age, gender, etc. have been added to TAM to examine their impacts on the PU and BI. For example, Kiefer (2005) found that demographic factors such as gender, age, and tenure are held as control variables, which negatively affected the work conditions of changes associated with personnel relationship to their organization. Indeed, their effects were directed at the PU (Viswanath Venkatesh & Bala, 2008). Thus, in this study, age, gender, tenure, and occupation were taken into account as demographic variables.

Age

In an organization, the age of employees can be crucial because it can be a risk factor in some situations such as job satisfaction, workplace autonomy, work intensity, mobility, and employees’ loyalty to their organization (Fabisiak & Prokurat, 2012). Age can also be a risk factor in the change process. For example, there are many different findings of the relationship between age and PU. Some researchers found that age had no significant effects on the variables of TAM, significantly in the studies of Bax and McGill (2009). However, older employees were more adaptable to change than younger employees (Chiu et al., 2001).

Additionally, the impact of PU on the intention to use IT was weaker in younger people than in older people (Pan & Jordan-Marsh, 2010; Vishwanath Venkatesh & Morris, 2000). Thus, the proposed hypothesis is designed to determine the effect of the age factor on the resistance to IT:

H4: The hospital personnel’s ages do not have any effect on their resistance to the hospital information system.

Gender

In the literature, there are many issues about the role of gender differences on technological change. As an exemplar, PU and PEU influence men and women differently. For example, women pay attention to PEU more than PU, and vice versa (Vishwanath Venkatesh & Morris, 2000). (Bax & McGill, 2009)concluded that women found the computer less useful than men, while they approach adaption to change more positively than men (Chiu et al., 2001). Owing to these distinctions, the following hypothesis is set:

H5: There is no relationship between the hospital personnel’s genders and their resistance to the hospital information system (IT).

Tenure

Tenure was found to be related with change process. The more changes there are in an organization, the more employees feel negatively about them (Kiefer, 2005). In another study, individual differences such as tenure, education level, and previous experiences had indirect effects on the intention of using technology (Agarwal & Prasad, 1999). According to a study by Majchrzak and Cotton (1988)), the workers who had less work experience were more committed to changes. Thus, a relevant hypothesis is established:

H6: There is no relationship between the hospital personnel’s longevity and their resistance to the hospital information system (IT).

Occupation

In one study, the resistance of physicians to hospital information systems was higher than in nurses (Lapointe & Rivard, 2005)we used a multilevel, longitudinal approach. We first assessed extant models of resistance to IT. Using semantic analysis, we identified five basic components of resistance: behaviors, object, subject, threats, and initial conditions. We further examined extant models to (1. However, these physicians worked there as independent entrepreneurs while the nurses worked under the administration. The main reasons for the resistance of physicians were the perceived loss of authority and power. On the contrary, it was remarked that physicians should be able to adapt to new technologies more than the other staff because of their professionalism and general competence (Hu et al., 2012). As a result, the following hypothesis was designed:

H7: There is no relationship between the hospital personnel’s occupation and their resistance to the hospital information system (IT).

METHOD

Research sample

This study is about the doctors and nurses working actively in Adana Numune Hospital in Adana province of Turkey. 950 surveys were handed over to authorized persons in the hospital, and 400 (42.1%) of the delivered surveys were collected. Some of the collected surveys were removed due to conflicting answers and blank responses, giving a total of 291 surveys that were included in the study. Personnel working in different departments ranging from cardiology to gynecology units were included in the study.

Research scale

Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) with 15 questions is widely used in the literature to evaluate the commitment of employees to their organization. However, Mowday et al. (1979) utilized six emotional commitment questionnaires for this purpose. The results showed strong evidence of internal consistency, pre-test post-test reliability, and covariance validity on OCQ. As a result, the authors have adopted this scale for this study.

There are many different scales in the literature to measure TAM parameters, but in this study, PU and PEU scales have been used, each consisting of ten questions. PU and PEU scales were chosen as they provided strong content validity (Benbasat & Moore, 1991). However, because there were closed questions, some questions were omitted, and six questions for each scale were taken into account.

A five-point Likert-type scale was used in the questionnaires (1 - strongly disagree, 2 - disagree, 3 - neither agree nor disagree, 4 - agree, 5 - ssstrongly agree). Averages of the six questions were taken to calculate the average levels of commitment, average perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use. In order to measure the resistance, the hospital employees responded with the binary options of 0 and 1 (0 - I did not resist, 1 - I showed resistance) to the question “Did you show resistance when using this system?”

Statistical analysis and reliability of the research

An SPSS 21 package program was used in the analysis of the data. The method of analysis used for the testing of hypotheses is the logistic regression analysis method. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to show that the scales explained the relevant factor. The maximum likelihood method was chosen as the extraction method. After the calculation, high factor loading items were found in the component matrix shown in Table 1. The absolute high values in the component matrix present a strong relationship between the item and related factor. Extraction method: maximum likelihood. 3 factors extracted and 18 iterations required.

According to the results of the factor analysis, the mentioned factors were grouped into three categories. However, two measurement items were not seen in appropriate categories. All of the perceived usefulness questions were collected together. Still, two questions measuring perceived ease of use and another one measuring affective commitment to the organization were included in another group. For this reason, these three questions were not included in the analysis because these items were not meaningful and did not contribute to the factors. The empty value on the table shows loadings, which are less than 0.30, and it was suppressed so that the table could be easily read. The items measuring Affective Commitment resulted in both negative and positive values in Table 1. The positive values explain the relevant factor absolutely better than negative values and, therefore, the negative values were ignored.

In the following Table 2, as a result of the exploratory factor analysis, a reliability analysis was performed to measure the reliability of the scale, and Cronbach’s α coefficient was calculated. Cronbach’s α coefficient was used to analyze the reliability of the scales. There is some argument that this coefficient should be 70%, even though it is reduced to 60% in exploratory studies (O’Fallon et al., 1973). For this reason, the authors used Cronbach's α coefficient to measure the consistency of the questionnaire before descriptive factor analysis.

The reliability of the perceived ease of use increased from 60.3% to 78.6%, and Cronbach’s α coefficient increased from 78.2% to 81.9%, as one question about commitment to the organization was omitted.

Table 1. Exploratory factor analysis - component matrix

|

Items |

Factor |

|||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

||

|

Perceived Usefulness (PU) |

PU1 |

0.721 |

- |

- |

|

PU2 |

0.554 |

- |

- |

|

|

PU3 |

0.713 |

- |

- |

|

|

PU4 |

0.612 |

- |

- |

|

|

PU5 |

0.726 |

- |

- |

|

|

PU6 |

0.682 |

- |

- |

|

|

Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) |

PUE1 |

- |

0.815 |

- |

|

PUE2 |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

PUE3 |

0.623 |

- |

- |

|

|

PUE4 |

0.603 |

- |

- |

|

|

PUE5 |

0.686 |

- |

- |

|

|

PUE6 |

0.689 |

- |

- |

|

|

Affective Commitment (AC) |

AC1 |

0.679 |

- |

-0.372 |

|

AC2 |

0.525 |

- |

- |

|

|

AC3 |

0.535 |

- |

-0.320 |

|

|

AC4 |

0.636 |

- |

-0.351 |

|

|

AC5 |

0.657 |

- |

-0.320 |

|

|

AC6 |

- |

0.345 |

- |

|

The reliability of all these scales, along with resistance, was found to be 0.895 for all 16 questions. Tolerance and VIF values were used to examine the multicollinearity problem among the questions in the scale (Table 3). The tolerance value is a term that directly measures the multicollinearity problem, and this term measures the amount of variability between the selected independent variables (O’Fallon et al., 1973).

Another term that gives information about the multicollinearity problem is the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value. Tolerance and VIF values are given in Table 3 below for all independent variables in the model.

The lower limit of the tolerance value should be 0.1 and the VIF values should not exceed 10. However, the ideal value should be between three and five (O’Fallon et al., 1973). Since all VIF values were less than 10 and all tolerance values were greater than 0.1, there was no multicollinearity problem between the independent variables.

Table 2. Reliability analysis of scales

|

Factors |

Items |

Mean |

Std. deviation |

N |

Cronbach’s alpha |

N of Items |

|

Perceived Usefulness (PU) |

PU1 |

3.5636 |

.90891 |

291 |

.851 |

6 |

|

PU2 |

3.3849 |

.91895 |

291 |

|||

|

PU3 |

3.5601 |

.96793 |

291 |

|||

|

PU4 |

3.5017 |

1.09347 |

291 |

|||

|

PU5 |

3.5842 |

1.03172 |

291 |

|||

|

PU6 |

3.5636 |

1.00614 |

291 |

|||

|

Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) |

PUE3 |

3.5155 |

.91101 |

291 |

.786 |

4 |

|

PUE4 |

3.4983 |

.95186 |

291 |

|||

|

PUE5 |

3.6632 |

.95952 |

291 |

|||

|

PUE6 |

3.6289 |

.97188 |

291 |

|||

|

Affective Commitment(AC) |

AC1 |

3.2887 |

1.17701 |

291 |

.819 |

5 |

|

AC2 |

3.2165 |

1.05595 |

291 |

|||

|

AC3 |

3.5086 |

1.10910 |

291 |

|||

|

AC4 |

3.3608 |

1.09720 |

291 |

|||

|

AC5 |

3.5326 |

1.05445 |

291 |

Table 3. Examination of a multicollinearity problem

|

Model |

Unstandardized coefficients |

Std. coeff. |

t |

Sig. |

Collinearity statistics |

||

|

B |

Std. error |

Beta |

Tolerance |

VIF |

|||

|

(Constant) |

2.154 |

.195 |

11.018 |

.000 |

|||

|

Perceived ease of use |

-.237 |

.055 |

-.281 |

-4.293 |

.000 |

.516 |

1.938 |

|

Perceived usefulness |

-.072 |

.045 |

-.109 |

-1.624 |

.106 |

.493 |

2.030 |

|

Affective commitment |

-.193 |

.043 |

-.295 |

-4.519 |

.000 |

.519 |

1.928 |

|

Gender |

.031 |

.059 |

.025 |

.521 |

.603 |

.930 |

1.075 |

|

Age |

-.031 |

.035 |

-.054 |

-.886 |

.376 |

.605 |

1.653 |

|

Tenure |

.045 |

.031 |

.078 |

1.435 |

.153 |

.739 |

1.353 |

|

Occupation |

.037 |

.044 |

.042 |

.837 |

.403 |

.877 |

1.140 |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sample

The distribution of the sample hospital employees according to their position in the hospital is shown in Table 4. As can be seen in Table 4, 291 hospital personnel were included in the study, with 56 (25 + 31) of them being doctors, 195 (17 + 178) of them nurses, and 40 (21 + 19) of them were working in other positions.

Table 4. Distribution of the personnel according to position, age, and gender

|

Gender |

Occupation |

Age group in year |

Total |

|||

|

Age |

18-24 |

25-34 |

35-44 |

45-54 |

||

|

Male |

Doctor |

0 |

6 |

12 |

7 |

25 |

|

Nurse |

4 |

11 |

2 |

0 |

17 |

|

|

Other |

4 |

8 |

9 |

0 |

21 |

|

|

Subtotal |

8 |

25 |

23 |

7 |

63 |

|

|

Female |

Doctor |

0 |

5 |

24 |

2 |

31 |

|

Nurse |

23 |

58 |

74 |

23 |

178 |

|

|

Other |

5 |

12 |

1 |

1 |

19 |

|

|

Subtotal |

28 |

75 |

99 |

26 |

228 |

|

|

Total |

36 |

100 |

122 |

33 |

291 |

|

All of the participants were below the age of 55 and the majority (99 + 23 = 122 persons) was between the ages of 35-44. The personnel involved in the survey were mostly women (228). They were mostly working as nurses (178). Most of the men working as doctors (12 people) were between 35-44 years old.

Logistic regression analysis results

Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the resistance of the hospital personnel to the hospital information system they used. As a method of logistic regression analysis, a stepwise forward likelihood ratio method was chosen. All hypotheses established in the study were evaluated at the 5% significance level. In the first step, all of the resistors (161) were correctly predicted, but the rate of those who did not resist could not be predicted, and the overall accuracy estimate was calculated to be 55.3% (Table 5).

Table 5. Initial model accuracy estimates

|

Observed |

Predicted |

||||

|

Resistance |

Percentage |

||||

|

No |

Yes |

||||

|

Step 0 |

Resistance |

No |

0 |

130 |

0.0 |

|

Yes |

0 |

161 |

100.0 |

||

|

Overall percentage |

55.3 |

||||

In the first step, constant coefficients and related statistics were calculated, and these values are given in Table 6 below. These statistics were Wald statistics, constant regression coefficient, and exponential logistic regression coefficient (odds ratio). Wald statistics explains the significance of the model.

Table 6. Logistic regression initial statistics

|

B |

S.E. |

Wald |

df |

Sig. |

Exp(B) |

||

|

Step 0 |

Constant |

.214 |

.118 |

3.290 |

1 |

.070 |

1.238 |

As shown in Table 7, the overall chi-square value of the model was 108.883 (p<0.05), meaning the model was significant at the 5% significance level. In other words, at least one of the variables presented in Table 7 could make the model more powerful. Since the highest independent variable was the “Perceived Ease of Use” variable among the chi-Square error values calculated for the independent variables to be included in the analysis, this was the first variable to be analyzed. This variable had a significant effect on the dependent variable, i.e. resistance (p <0.05 for chi-Square = 83.486).

Other variables with a significant effect on the dependent variable were analyzed at each step according to the chi-square value they got.

Table 7. Initial model showing significance levels of all variables

|

Independent Variables |

Score |

df |

Sig. |

||

|

Step 0 |

Variables |

Gender(1) |

.810 |

1 |

.368 |

|

Perceived Usefulness |

65.703 |

1 |

.000 |

||

|

Perceived Ease of Use |

83.486 |

1 |

.000 |

||

|

Affective Commitment |

80.430 |

1 |

.000 |

||

|

Occupation |

5.975 |

1 |

.015 |

||

|

Tenure |

.041 |

1 |

.839 |

||

|

Age |

17.172 |

1 |

.000 |

||

|

Overall statistics |

108.883 |

7 |

.000 |

||

A logistic regression model was conducted through a stepwise method and each significant variable was put sequentially in the model according to their score shown in Table 7. In each step, the model was supposed to be better from the previous one. This process continues until the overall chi-square is statistically insignificant. In Table 7, the effect of the variables “Gender” and “Tenure” on resistance was not statistically significant (p => 0.05) in the initial model. These factors were excluded from the model since they do not have the potential to improve the model. Factors such as “Occupation” and “Age” also were insignificant, and they do not contribute to the model, resulting in these variables being extracted from the model. The model achieved the best result in three steps. These changes were not considered because the changes after the fourth iteration were below 0.001.

Coefficient estimates calculated for the conceptual logistic regression model are listed in Table 8.

Table 8. Coefficient estimates for conceptual model variables

|

B |

S.E. |

Wald |

df |

Sig. |

Exp(B) |

95% CI.for EXP(B) |

|||

|

L |

U |

||||||||

|

Step 1a |

Perceived_ Ease of Use |

-2.850 |

.372 |

58.839 |

1 |

.000 |

.058 |

.028 |

.120 |

|

Constant |

10.332 |

1.343 |

59.172 |

1 |

.000 |

30706.546 |

|||

|

Step 2b |

Perceived_ Ease of Use |

-2.257 |

.419 |

28.953 |

1 |

.000 |

.105 |

.046 |

.238 |

|

Affective Commitment |

-1.854 |

.352 |

27.754 |

1 |

.000 |

.157 |

.079 |

.312 |

|

|

Constant |

14.745 |

1.854 |

63.223 |

1 |

.000 |

2532673.116 |

|||

|

Step 3c |

Perceived_ Usefulness |

-1.509 |

.427 |

12.479 |

1 |

.000 |

.221 |

.096 |

.511 |

|

Perceived_ Ease of Use |

-1.859 |

.447 |

17.319 |

1 |

.000 |

.156 |

.065 |

.374 |

|

|

Affective Commitment |

-1.719 |

.374 |

21.190 |

1 |

.000 |

.179 |

.086 |

.373 |

|

|

Constant |

18.464 |

2.410 |

58.705 |

1 |

.000 |

104413761.55 |

|||

The independent variables of the model together entered the model in the last third stage, and the effects of the variables entering the model on the resistance were significant (p<0.05). The Wald statistic shows the significance of the model and the contribution of each variable to the model. If the third step is taken into consideration, it can be seen that the most contributing variable to the model was the ‘perceived ease of use’ variable. Apart from that, the value of Exp (B) indicates the ratio of Odds (actual), and one unit of change in the independent variable shows the amount of change in the dependent variable.

The variables that contributed to the logistic regression model in the last step were found to be the ‘perceived ease of use and the perceived utility of the information system and affective commitment to the organization.’ The logistic regression model that emerges with the probability of showing resistance to information systems “p” can be formulated as follows:

AC: Affective Commitment, PEU: Perceived Ease of Use and PU: Perceived Usefulness

Logit (p) = 18.464 - 1.719 (AC) - 1.859 (PEU) -1.509 (PU) (1)

In the logistic regression method, the sign of the coefficient indicating the relation between the independent variable and the dependent variable being positive indicates the probability of the increase in the dependent variable of the increase seen in the independent variable. The negative relationship reduces the probability of the dependent variable. In this model, the resistance decreases with the increase of these three variables entering the model.

In the exponential coefficients, if the direction of the relationship is over 1.0 it indicates a positive relationship, and if it is less than 1.0 it indicates a negative relationship. The Exp (B) values of the independent variables in the model were less than 1 and the sign was negative in both the coefficient and the equation. A one-unit increase in perceived usefulness will reduce resistance by 0.221 times, a one-unit increase in affective commitment to the organization will reduce resistance by 0.179, and a one-unit increase in perceived ease of use will reduce resistance by 0.156 times. The affective commitment to the organization would cause a reduction of about 17.9% in resistance to the hospital information system compared to those with less affective commitment.

Similarly, resistance to information systems, which had higher perceived usefulness, was 15.6% less likely when compared to those with lower perceived usefulness. The most influential variable was the system’s ease of use, and easier-to-use information systems would cause a reduction in resistance of about 22.1% when compared to hard-to-use information systems.

Goodness of model fit

To interpret the goodness of model, the values of Cox & Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2 were used. For each iteration, -2 Log likelihood and Cox & Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2 values were calculated, and in the next step, the resultant values were better than the previous one (Table 9). The parameter “-2 Log likelihood” reflects the chi-square value used in order to test the overall model significance. The closer to zero the parameter is, the better the observed variables in the model are represented. In each step, the parameter is supposed to be an improvement over the previous one.

The values of Cox & Snell R2 and Nagelkerke R2 represent the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variable(s), such as the R2 value of the multiple regressions, and these two R2 values are different since they are estimated from different paths.

Table 9. The parameters of goodness of model

|

Step |

-2 Log likelihood |

Cox & Snell R2 |

Nagelkerke R2 |

|

1 |

296.894a |

.299 |

.400 |

|

2 |

255.738b |

.391 |

.523 |

|

3 |

241.586c |

.420 |

.562 |

Nagelkerke R2 is calculated since Cox & Snell R2 never reaches 1 and, therefore, is not so easy to interpret (Field, 2005; Garson, 2008). Examining the values of Nagelkerke R2 presented in Table 9, when only the “perceived ease of use” independent variable is entered in the first step, it explains 40% of the variance in resistance. For each additional variable, the R2 values improved at each step, and the last step took the best value as the result of the other variables entering the analysis. As seen in the last step, the three variables contributing to the model account for about 56.2% of resistance against information systems. This reveals the difference between the initial model and the stepwise model.

When the classification obtained from the stepwise logistic regression model is examined, in the first step, that is, the classification made according only to the perceived ease of use independent variable, 117 of the 161 personnel in the group of resistors were correctly estimated, 44 were incorrectly estimated and the correct guess rate was 72.7.

The rate of the correct estimate of non-resistance was found to be 71.5%. Because of 161 people who did not resist, 93 were classified as unresistant. The remaining 37 people were misclassified. In this case, the overall estimate accuracy rate was calculated as 72.2%. With the addition of other variables, the correct estimation rates increased, and in the last step, the overall accuracy rate increased to 80.8%. Another compliance indicator is the Hosmer and Lemeshow test. Also known as the chi-square goodness-of-fit test, it provides the possibility of seeing the logistic regression model as a whole.

Table 10. Classification table

|

Observed |

Predicted |

||||

|

Resistance |

Percentage |

||||

|

No |

Yes |

Correct |

|||

|

Step 1 |

Resistance |

No |

93 |

37 |

71.5 |

|

Yes |

44 |

117 |

72.7 |

||

|

Overall Percentage |

72,2 |

||||

|

Step 2 |

Resistance |

No |

103 |

27 |

79.2 |

|

Yes |

36 |

125 |

77.6 |

||

|

Overall Percentage |

78,4 |

||||

|

Step 3 |

Resistance |

No |

105 |

25 |

80.8 |

|

Yes |

31 |

130 |

80.7 |

||

|

Overall Percentage |

80.8 |

||||

Table 11. Hosmer and Lemeshow test result

|

Step |

Chi-square |

df |

Sig. |

|

1 |

2.553 |

7 |

.923 |

|

2 |

10.892 |

8 |

.208 |

|

3 |

13.813 |

8 |

.087 |

In Table 11, the Hosmer and Lemeshow tests were calculated for each of the three steps, and the results of all steps were meaningless (p>0.05). To say that this test is meaningless is to accept that there is no difference between the given data and the proposed logistic regression model (Hosmer et al., 1991). In this sense, as a result of the Hosmer and Lemeshow test in this study, the fact that the available model was good, i.e. there was no difference between the proposed model and the observed values were obtained (0.087>0.05).

In the logistic regression, one of the criteria for model fit is the accuracy of estimates. The more accurately the model is predicted, the more compatible it is. If the initial classification results presented (Table 5) are to be recalled, the correct classification rate was found to be 55.3%; 161 persons in the resistance group and 130 persons in the non-resistance group (observed condition).

Hypothesis testing and summary

The conclusion of hypothesis tests suggested for the conceptual model is listed in Table 12 below.

Table 12. Hypothesis test results

|

Hypothesis |

Test results |

|

H1=PU -->Resistance |

Yes |

|

H2=PEU-->Resistance |

Yes |

|

H3= AC -->Resistance |

Yes |

|

H4=Age-->Resistance |

No |

|

H5=Gender-->Resistance |

No |

|

H6=Tenure-->Resistance |

No |

|

H7=Occupation-->Resistance |

No |

In the conceptual model, the effect of the years worked in the hospital, age of the employee, gender of the employee and occupation in the workplace variables on the demonstrated resistance to the hospital information system was not observed.

CONCLUSION

This study took doctors, nurses and other health personnel working in a hospital in Adana province in Turkey into consideration. It investigated the impact of affective commitment of the personnel to the organization, the perceived usefulness and the perceived ease of use of the information system they used, and certain demographic characteristics of the personnel on the resistance to the hospital information system they used. A logistic regression method was chosen as the research method. At the end of the study, it was determined that the age, gender, position, and working time of the hospital personnel were not effective on the resistance to the hospital information systems. However, it was concluded that the information systems’ perceived usefulness and ease of use and the affective commitment of personnel to the organization had an effect on the resistance they showed to these systems. These variables were found to be inversely related to the resistance to the information systems.

Although the point of the scale used in this analysis was nominal, the results are very similar to previous studies. For example, TAM studies have shown that the perceived usefulness and ease of use have a positive effect on the acceptance of information systems (Davis, 1989; Oreg, 2003). The findings in this study confirm Davis’s original model. As expected, the TAM factors have been negatively related to the resistance of technology. In this sense, the study was also parallel to the results of TAM studies. One of the findings of this study was that the strength of PEU on resistance was stronger than PU. In contrast, the relationship between PEU and TA is weaker than the relationship between PU and TA according to the study of Ma and Liu (2005). It shows that technology was resisted strongly when technology was not easy to use compared to its effect on the acceptance of it.

Another finding of this study was the negative relationship between the affective commitment of employees and the resistance to technology. This supports a study conducted by Peccei et al. (2011), who found that the usefulness of change and organizational commitment had a negative effect on the resistance to change. This study is consistent with other studies as well. For example, organizational commitment was found as one of the most important determinants of organizational change (Iverson, 1996; Mossholder et al., 2000; Nafei, 2014; Schalk et al., 1998; Visagie & Steyn, 2011)support and participation. The relationship between these processes and employee behaviour was examined by testing a theoretical model, in which two mediating concepts are used: the psychological contract and employee job attitudes. The research was carried out in two main divisions of a large telecommunications firm on a sample of 220 employees. The theoretical model (perceived change implementation influencing the psychological contract, influencing employee attitudes, influencing employee behaviour. The findings of this study differ from Czaja and Sharit (1998), who pointed out that easy-to-use tasks had a positive effect on usage compared to others. However, it has been determined that the age factor was effective on the ease of use and perceived usefulness, and the elderly could identify the benefits more than the younger ones.

Age did not significantly influence resistance to IT in this study, and this finding is consistent with the study of Bax and McGill (2009), whereas some researchers reported that age had an effect on the intention of physicians to use electronic records (Chiu et al., 2001; Viswanath Venkatesh et al., 2011; Walter & Lopez, 2008). One reason can be the average age of personnel in the examined organization as they were mostly mid-aged. In this study, the relationship between gender and the resistance of employees to IT was not significant. This finding is contrasted by other studies (Bax & McGill, 2009; Chiu et al., 2001), but on a par with the findings of Viswanath Venkatesh et al. (2011), who stated that gender had no impact on the use of computers. The result regarding gender in this study also did not comply with the other studies in the literature. For example, Gosavi (2017) found that firms that have a female owner adopt the Internet more than the firms that have a male owner.

One of the results of this study is that tenure did not affect resistance to IT. This finding is in accordance with that of Agarwal and Prasad (1999). However, Kiefer (2005) found that the tenure effect depended on the implementation frequency of change in the organization. The profession of healthcare personnel in this study also had no significant effect on the resistance to IT. However, (Lapointe & Rivard, 2005) stated that the resistance to IT differs from nurses to physicians in cases where the physicians were administrators.

In summary, factors such as perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and affective commitment, have affected the resistance to information systems negatively and are compatible with the literature, while the other factors such as gender, profession, and tenure have remained uncertain. The age factor was incompatible with previous studies.

This study has underscored that organizational affective commitment has an effect on the resistance to IT, as well as the other factors like perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness of IT. The organization could have troubles in the change process, both in pre- and post-implementation phases, in spite of their openness to change and keeping up with technological changes but for their commitment. Thus, gaining the emotion of personnel is an inevitable part of change management as well as sustainability in working performance. As a result, the employee does not just do what he/she needs to do; he/she also does what he/she does best. It is not expected that organizations, whose personnel have bad relationships with them will achieve their goals. Knowing personnel’s attitude to work or any change process provides an advantage because of the previous prediction of them; further increasing awareness of their personnel’s commitment to themselves by assessing their current situation is relevant. Therefore, they can take essential precautions in order to achieve better quality service to the patient and increase patient satisfaction. Eventually, they both can challenge their competitors and enhance trust and good image on patients.

The organization should pay attention to the factors that appear to be effective on the resistance to IT. By this means, potential resistance could be predicted before any change, and the necessary precautions could be taken accordingly. Unless steps are taken to understand and solve these behavioral and/or social problems, the benefits of the millions of dollars that organizations spend on the development of their information systems will be minimized (Langefors, 1978). Consequently, an employee might leave an organization because of job dissatisfaction and lower commitment (Laumer, 2012).

Implications for managers

It is important for administrators to focus on the pace of change, especially before implementation, in terms of the need to predict user resistance, which may lead to potential conflicts and changes to failure (Meissonier & Houzé, 2010) we conceptualise a whole theoretic-system we call IT Conflict-Resistance Theory (IT-CRT. Necessary measures can be taken if the displayed resistance to innovation in organizations can be predicted. The unpredicted change makes it more challenging to respond more effectively, whereas the predicted change gives time for the preparation of change (Appelbaum & Wohl, 2000). High diversity of personnel is a fundamental issue in hospitals due to the existence of different age groups and professions. According to Thamhain (2011), promoting commitment was one of the ten guidelines for working effectively with culturally diverse project teams. Therefore, managers in IT implementation should find ways to increase the commitment of personnel.

It is complicated for a company whose employees have a low sense of commitment to have a successful output. Organizations that give importance to the effects of their employees have better financial returns (Authayarat & Umemuro, 2012). Thus, the organization also earns the commitment of its employees by providing job security, status, and other non-material prizes to them during the change transition. As a result, the process of change becomes more manageable, more effective, and faster.

Managers should see the resistance not as a threat but as an opportunity to be aware of their weaknesses so that they can improve both the relationship between management and their personnel and the designs of used information systems in their organization. Furthermore, managers should predict the potential resistance of personnel by using related prediction techniques like simulation and statistical analyses by looking back at their past performances and current behavior. The manager should inform employees about new changes and make them ready for change. Otherwise, it can cause misunderstanding amongst employees, and some negative consequences regarding their work and health, as Laumer (2012) stated.

Should the managers determine resistance regarding some emotional situation or affective commitment, then they must communicate with their personnel to gain their trust and ensure their personal continuity in the organization. Thus, managers should develop strategies to gain the personnel’s commitment to themselves and to the hospital. For example, Japanese companies show the importance they give to their employees with the win-win strategy. They try to win them with strategies such as providing lifetime employment, profit sharing, intensive in-service training and senior-based compensation, high levels of sincerity, and participatory decision-making (White & Trevor, 1983).

It is important to involve personnel in current and future change processes so that they can approach the change and choose how to function cooperatively. Consequently, they can take responsibility for creating the results of change and making the system strong (Rothwell et al., 2010). For this reason, managers should create an open platform for enhancing suggestions and complaints from personnel about the new system and assessing the existing climate in the workplace before making any changes. Thus, future change processes could be deployed more easily and on time in the hospital through gaining the personnel’s commitment by involving them in both the decision-making related to the change process and change process itself.

Limitation and future work

This research takes into consideration the affective commitment of the hospital personnel to the organization, the perceived usefulness and the ease of use of the information systems, and the demographic characteristics of the hospital personnel. Since the information system used in each hospital would differ from one another, the way employees perceive it might be different. This is because personnel, who are highly committed to the organization and act in the direction of the organizational objectives, might be able to withstand the potential disadvantages of the information system. In such a case, it would be evident why the personnel who are emotionally committed to the organization are resistant to innovation. For this reason, further research should consider the characteristics of different information systems. Additionally, as there will be resistance, if it is not comfortable to use, the system developer should improve the use of technology. However, ease of use may differ from age to age. Therefore, future research should examine whether the ease of use of technology alters with age or not.

Furthermore, the sample size should be increased, or other hospitals should be included in the study, and the research should be extended. In addition, the characteristics of the information systems in the relevant hospital should be evaluated separately. Finally, the next study should include differences in hospital type, consider information systems, and compare the results.

References

Agarwal, R., & Prasad, J. (1999). Ritu Agarwal. Decision Sciences, 30(2), 361–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1999.tb01614.x

Al-Haddad, S., & Kotnour, T. (2015). Integrating organisational change literature. Journal of Organisational Change Management, 28(2), 234–262. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-11-2013-0215

Ali, M., Zhou, L., Miller, L., & Ieromonachou, P. (2016). User resistance in IT: A literature review. International Journal of Information Management, 36(1), 35–43.

Anderson, L. A., & Anderson, D. (2010). The Change Leader’s Roadmap: How to Navigate Your Organization’s Transformation. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Appelbaum, S. H., & Wohl, L. (2000). Transformation or change: Some prescriptions for health care organizations. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 10(5), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520010345768

Armenakis, A. A., Harris, S. G., & Mossholder, K. W. (1993). Creating readiness for organizational change. Human Relations, 46(6), 681–703.

Authayarat, W., & Umemuro, H. (2012). Affective management and its effect on management performance. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 8(2), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.7341/2012821

Bakan, İ. (2011). Örgütsel bağlılık: Kavram, kuram, sebep ve sonuçlar [Organizational Commitment: Concept, Theory, Causes and Effects]. Gazi.

Baker, M. (2009). My involvement in engineering management during its pioneer years. Engineering Management Journal, 21(3), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10429247.2009.11431809

Barutçugil, İ. (2013). Stratejik yönetim [Strategic Management]. Kariyer Yayıncılık.

Bax, S., & McGill, T. (2009). From beliefs to success: Utilizing an expanded tam to predict web page development success. Cross-Disciplinary Advances in Human Computer Interaction: User Modeling, Social Computing, and Adaptive Interfaces, 3(3), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-60566-142-1.ch003

Beer, M., & Nohria, N. (2000). HBR’s 10 must reads on change. Harvard Business Review, 78(3), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0000000000000208

Benbasat, I., & Moore, G. C. (1991). Development of an instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an information technology innovation. Information Systems Research, 2(3), 192–222.

Bertolini, M., Bevilacqua, M., Ciarapica, F. E., & Giacchetta, G. (2011). Business process re-engineering in healthcare management: A case study. Business Process Management Journal, 17(1), 42–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/14637151111105571

Bhattacherjee, A., & Hikmet, N. (2007). Physicians’ resistance toward healthcare information technology: A theoretical model and empirical test. European Journal of Information Systems, 16(6), 725–737. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000717

Buntin, M. B., Burke, M. F., Hoaglin, M. C., & Blumenthal, D. (2011). The benefits of health information technology: A review of the recent literature shows predominantly positive results. Health Affairs, 30(3), 464–471. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0178

Chiu, W. C. K., Chan, A. W., Snape, E., & Redman, T. (2001). Age stereotypes and discriminatory attitudes towards older workers: An East-West comparison. Human Relations, 54(5), 629–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726701545004

Cook, J., & Wall, T. (1980). New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non-fulfillment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1980.tb00005.x

Czaja, S. J., & Sharit, J. (1998). Age differences in attitudes toward computers. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53(5), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/53B.5.P329

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 13(3), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

DeSanctis, G., & Courtney, J. F. (1983). Toward friendly user MIS implementation. Communications of the ACM, 26(10), 732–738. https://doi.org/10.1145/358413.358419

Duimering, P. R., Elhedhli, S., Jewkes, B., & Smucker, M. D. (2013). Management engineering: The engineering of management systems. A discussion paper. Retrieved from http://docplayer.net/11969146-Management-engineering-the-engineering-of-management-systems-a-discussion-paper-by.html

Eckhardt, A., Laumer, S., & Weitzel, T. (2009). Who influences whom? Analyzing workplace referents’ social influence on IT adoption and non-adoption. Journal of Information Technology, 24(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2008.31

Fabisiak, J., & Prokurat, S. (2012). Age management as a tool for the demographic decline in the 21st century: An overview of its characteristics. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 8(4), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.7341/2012846

Field, A. (2005). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. London: Sage Publications.

Foster, S., & Wilson-Evered, E. (2006). A multidisciplinary approach to assess readiness for change in enterprise system implementations a multidisciplinary approach to assess readiness for change in enterprise system implementations. Proceedings of the 20th ANZAM Conference, 1–22. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f0dd/8887a41ee97872df7fe06990cf3bf623d589.pdf

Frambach, R. T., & Schillewaert, N. (2002). Organizational innovation adoption: A multi-level framework of determinants and opportunities for future research. Journal of Business Research, 55(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00152-1

Garson, G. D. (2008). Logistic Regression: Statnotes. North Carolina: North Carolina State University.

Gosavi, A. (2017). Use of the Internet and its impact on productivity and sales growth in female-owned firms: Evidence from India. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 13(2), 155–178. https://doi.org/10.7341/20171327

Hadjimanolis, A. (2003). The barriers approach to innovation. In L.V Shavinina (Ed.), The International Handbook on Innovation (pp. 559-573). Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044198-6/50038-3

Hosmer, D. W., Taber, S., & Lemeshow, S. (1991). The importance of assessing the fit of logistic regression models: A case study. American Journal of Public Health, 81(12), 1630–1635. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.81.12.1630

Hu, P. J., Chau, P. Y. K., Sheng, O. R. L., & Tam, K. Y. (2012). Examining acceptance model using physician of acceptance telemedicine technology. Journal of Management Information Systems, 16(2), 91–112.

Iverson, R. D. (1996). Employee acceptance of organizational change: The role of organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/09585199600000121

Jiang, J. J., Klein, G., & Crampton, S. M. (2000). A note on SERVQUAL reliability and validity in information system service quality measurement. Decision Sciences, 31(3), 725–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.2000.tb00940.x

Joia, L. A., Gradvohl De Macêdo, D., & Gaete De Oliveira, L. (2014). Antecedents of resistance to enterprise systems: The IT leadership perspective. Journal of High Technology Management Research, 25(2), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hitech.2014.07.007

Jones, R. A., Jimmieson, N. L., & Griffiths, A. (2005). The impact of organizational culture and reshaping capabilities on change implementation success: The mediating role of readiness for change. Journal of Management Studies, 42(2), 361-386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00500.x

Joshi, K. (1991). The change: Information systems technology implementation. MIS Quarterly, 15(2), 229–242.

Keen, P. G. W. (1981). Information systems and organizational change. Communications of the ACM, 24(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1145/358527.358543

Kiefer, T. (2005). Feeling bad: Antecedents and consequences of negative emotions in ongoing change. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(8), 875–897. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.339

Klaus, T., & Blanton, J. E. (2010). User resistance determinants and the psychological contract in enterprise system implementations. European Journal of Information Systems, 19(6), 625–636. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2010.39

Kotter, J. P., & Schlesinger, L. A. (2008). Choosing strategies for change. Harvard Business Review, July-August. Retrieved from https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/files/sdpfellowship/files/day3_2_choosing_strategies_for_change.pdf

Krovi, R. (1993). Identifying the causes of resistance to IS implementation. A change theory perspective. Information and Management, 25(6), 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-7206(93)90082-5

Langefors, B. (1978). Discussion of the article by Bostrom and Heinen: MIS problems and failures: A socio-technical perspective. Part I: The causes. MIS Quarterly, 2(June), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/248942