Received 30 October 2018; Revised 10 February 2019, 25 February 2019; Accepted 27 February 2019

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Marco Pini, Senior Economist, Unioncamere-Si.Camera, via Nerva, 1, 00199 Rome, Italy, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

This paper tests the impact of different types of management within family businesses on digital innovation related to Industry 4.0 investments, from a geographical perspective. The data set consists of 3,000 Italian manufacturing small- and medium–sized enterprises. Using probit models, the results show that while in the more advanced area (center-north) external management affects the propensity for innovation significantly, in the less developed area (Southern Italy) external management requires an additional and simultaneous investment in R&D to drive a firm’s innovation. This suggests that innovation policy should define incentives that also help enhance new management business models and take into account behavioral features of different firms in relation to the level of the development of the geographical areas in which they operate.

Keywords: family businesses, Industry 4.0, manufacturing, regions

INTRODUCTION

Since the first studies on entrepreneurship (Schumpeter, 1934) and the business cycle and economic performance (Freeman, 1987), innovation has been a subject of investigation. Innovation has been examined in relation to the society, through the concept of the National Innovation System (Lundvall, 1992; Nelson & Rosenberg, 1993; Niosi, Saviotti, Bellon, & Crown, 1993; OECD, 1999; Edquist, 2005; Asheim, Isaksen, Nauwelaers, & Tödling, 2003). The subject has also been addressed from a territorial point of view (Acs, 2000; Autio, 1998; Bathelt & Depner, 2003; Braczyk, Cooke, & Heidenreich, 1998; Cooke, Boekholt, & Tödling, 2000; de la Mothe & Paquet, 1998; Doloreux, 2002; Fornhal & Brenner, 2003; Howells, 1999; Mytelka, 2000; Moulaert & Sekia, 2003) through the introduction of the Regional Innovation System approach (Autio, 1998; Braczyk et al., 1998; Cooke et al., 2000), which focused on innovation clusters (Audretsch & Feldman, 1996), interdependencies among regions, innovation networks (Boschma & Frenken, 2009) and other themes related to spatial analysis. These new developments in addressing innovation have taken territorial and microeconomic perspectives, highlighting the importance of the absorption capacity of a firm (Tödtling & Trippl, 2005) and the ability to adapt to the structural changes in less-developed, compared to more advanced, regions.

The behavioral characteristics linked to the management and organization of enterprises, also based on innovation capabilities (Aas & Breunig, 2017), particularly for SMEs, were not considered until the 1990s (Lagendijk, 2000): the main innovation factors taken into account were primarily R&D, infrastructure, financial support, and technology transfer. It has become increasingly clear that there is no “best practice” in innovation policy (see also Cooke et al., 2000; Isaksen, 2001; Nauwelaers & Wintjes, 2003), but only policies considering macroeconomic features of the regions and microeconomic features at a firm level. Nauwelaers and Wintjes (2003) divide policy instruments into two: firm-oriented and regional system-oriented.

Stimulating innovation only through the transfer of financial resources may be unsuccessful if the firms lack managerial and organizational competencies (Cobbenhagen, 1999). Many studies view management as one of the main subjects of regional innovation policies (Smallbone, North, Roper & Vickers, 2003; Cooke, 2001; Nauwelaers & Wintjes, 2003; Tödtling & Trippl, 2005). Focusing on the firm level, Family Businesses (FBs) play an important role across all economies (Aronoff & Ward, 1995; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, 1999; Neubauer & Lank, 1998). According to Mandl (2008), in the EU countries, FBs represent at least two-thirds of the total number of enterprises, while in Italy the share is over 90% (Ferri, Pini, & Scaccabarozzi, 2014).

Within a company the different levels of family involvement in ownership and management may affect the technological innovation process arising from diverse resource management and deployment methods (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003), risk aversion (Gómez-Mejía, Haynes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson, & Moyano-Fuentes, 2007; Cucculelli, Mannarino, Pupo, & Ricotta, 2014; Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2006; Naldi, Nordqvist, Sjöberg, & Wiklund, 2007; Bianco, Bontempi, Golinelli, & Parigi, 2013; Chrisman, Chua, De Massis, Frattini, & Wright, 2015), and long-term vision (Le Breton-Miller & Miller, 2006; Manso, 2011).

In Italy, FBs are characterized by a stronger presence of family members in their management than in other countries (Bank of Italy, 2009; Giacomelli & Trento, 2005; Bianchi, Bianco, Giacomelli, Pacces, & Trento, 2005; Bloom, Sadun, & van Reenen, 2008), and there is a reluctance to outsource management (Bloom et al., 2008). Few empirical studies on the role of management within FBs in terms of technological innovation have been conducted (Craig & Moores, 2006; Kotlar, De Massis, Frattini, Bianchi, & Fang, 2013; Matzler, Veider, Hautz, & Stadler, 2015), particularly from a territorial perspective, which is relevant in a country such as Italy where there are wide socio-economic disparities between the Centre-North and the South.

Finally, most studies on FB management in Italy specifically focus only on product or process innovation (Cucculelli, Le Breton-Miller, & Miller, 2016; Minetti, Murro, & Paiella, 2015). Digitalization (Xu, Xu, & Li, 2018) has become the new technology framework in the current technological age (or Fourth industrial revolution, Schwab, 2016). Many advanced countries and supranational institutions have adopted innovation policies – defined as Industry 4.0 – based on digital technological innovation development, with particular regard to small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Crnjac, Veža, & Banduka, 2017; Geissbauer, Vedso, & Schrauf, 2016; European Commission, 2017; Cassetta & Pini, 2018; Dileo & Pini 2018; Pini, Dileo, & Cassetta, 2018). Industry 4.0 is already at the forefront of the strategic agenda of many companies (PWC, 2016) as a push factor to ensure their competitive edge.

Industry 4.0 is, therefore, an important topic from a regional perspective (Ciffolilli & Muscio, 2018) and represents an opportunity to relaunch a firm’s competitiveness in less developed areas. It can thus, potentially contribute to reducing territorial gaps. Many scholars suggest that Industry 4.0 requires not only ICT investments but also new business models and business process management, and a high level of expertise (Xu et al., 2018; Liao, Deschamps, Loures, & Ramos, 2017; Lorenz, Ruessmann, Strack, Lueth, & Bolle, 2015; Schneider, 2018; Almada-Lobo, 2016), so the subject of management within FBs becomes even more relevant. Only a few analyses focus on Industry 4.0 (for a review see Liao et al., 2017; Moeuf, Pellerin, Lamouri, Tamayo-Giraldo, & Barbaray, 2018) and particularly within Italy, but only at a country level (Cassetta & Pini, 2018; Dileo & Pini 2018).

Therefore, due to this lack of research, the current study focuses on innovation related to Industry 4.0 and associated with entrepreneurial models within FBs from a territorial perspective. The study investigates whether in less developed regions FBs run by outside managers show a higher propensity to innovate (investing in Industry 4.0) than those where the managers are family members. The study also highlights the differences in more developed areas. We consider Southern Italy as our less-developed region because the competitiveness gap of this area is evident in the GDP per capita, which is 44% lower than that of the Centre-North. The analysis uses a survey conducted in 2018 on a sample of 3,000 Italian manufacturing SMEs with between 5 and 249 employees.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Family businesses are important for the economic production of all countries (Aronoff & Ward, 1995; La Porta et al., 1999; Neubauer & Lank, 1998). According to the literature (Le Breton-Miller, Miller, & Lester, 2011), FBs are divided into the two categories of firms managed by family members (included the owner) and by external managers. This distinction is very important as family involvement in ownership and management can affect innovation propensity in different ways, such as the methods of resource management and deployment (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003); risk aversion degree (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Cucculelli et al., 2014; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2006; Naldi et al., 2007; Bianco et al., 2013; Chrisman et al., 2015); debt financing and new ventures investments (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006; Cabrera-Suárez, De Saá-Pérez, & García-Almeida, 2001; Carney, 2005; Naldi et al. 2007; Villalonga & Amit, 2006); entrenchment and personalism level (Gómez-Mejía, Núñez-Nickel, & Gutierrez, 2001; Schulz, Lubatkin & Dino, 2003; Chrisman, Chua, & Litz, 2004; De Massi, Frattini, Pizzurno, & Cassia, 2015); short- and long-term company interests (Davi, Schoorman, Mayer, & Tan 2000; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2006; Manso, 2011); and various incentives (Ang, Cole, & Lin, 2000; Demsetz, 1988; Fama & Jensen, 1983a, 1983b).

This view relates to the acknowledged importance of management within regional policies. Smallbone et al. (2003) consider the distinct organizational culture linked to the proximity between ownership and management, which is one of the three SME characteristics for innovation policies. Cooke (2001) identifies among the innovation factors superstructural elements linked to the governance of firms, in addition to the infrastructural elements such as finance, telecom, and transport infrastructures. Nauwelaers and Wintjes (2003) identify the subsidy for hiring innovation managers in SMEs and the innovation management training and advice among the policy innovations at a firm level. Tödtling and Trippl (2005) point out the need for management schools, which can raise the education/skill level of a region (Leon, 2017).

The effect of inside vs. outside managers within the family businesses on performance has been variously analyzed, with mixed results. In Agency theory (Schulze, Lubatkin, Dino, & Buchholtz, 2001), it is assumed that when there is an alignment between owners and managers there is no information asymmetry (Chrisman et al., 2004; Gómez-Mejía et al., 2001; Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Fama & Jensen, 1983a, 1983b) or different incentives (Ang et al., 2000; Demsetz, 1988; Fama & Jensen, 1983a, 1983b): so agency costs can be advantageously low (for a measure of agency cost, see Ang et al., 2000).

Non-family managers can have short-run interests and, as agents, pursue their own personal goals rather than those of their principals (Fama & Jensen, 1983b; Jensen & Meckling, 1976): this generates free-ride problems. The owner-manager instead has the incentive and the knowledge to run the business well and has a far-sighted vision that can generate superior performance (Hoopes & Miller, 2006; Jayaraman, Khorana, Nelling, & Covin, 2000).

Nevertheless, non-family managers can avoid problems of excessive entrenchment, altruism, and personalism (Schulze et al., 2003; Chrisman et al., 2004) that can be associated with the family-manager case. In fact, family managers can pursue goals different from profit or firm value maximization (Chrisman, Chua, Pearson, & Barnett, 2012), which can lead to mismanagement or under-management of the business (Schulze et al., 2003; Westhead & Howorth, 2007), and conflicts of interests within the family (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2001; Schulze et al., 2003). Thus, personalism and particularism may negatively affect the innovation process (De Massis et al., 2015). In addition, the close connection between family and firm assets means that the owner-manager may have greater risk aversion, which may hinder innovation activities (Cucculelli et al., 2014; Chrisman et al., 2015).

Second, the stewardship theory is linked to the concepts of “familiness” (Habbershon & Williams, 1999), and family capital (Hoffman, Hoelscher, & Sorenson, 2006), and focuses more on social capital than on financial or economic aspects. This theory states that when managers are family members or emotionally linked to the family, there is more stimulus to pursue long-term interests (Davis, Schoorman, Mayer, & Tan, 2000; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2006), which are essential to supporting innovation productivity (Manso, 2011; Bratnicka-Myśliwiec, Wronka-Pośpiech, & Ingram, 2019). The family managers act with altruism to achieve the best for the company, its stakeholders and the organizational collective (Davis, Schoorman, & Donaldson, 1997; Donaldson & Davis, 1991; Fox & Hamilton, 1994: Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2005), devoting attention to job security, social contribution, belonging and standing within the family (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Miller, Le Breton-Miller, & Scholnick, 2008). However, family managers may tend to preserve their power and authority even at the cost of hindering the firm’s potential economic benefits (Kotlar et al., 2013), which can also involve the innovative process (Matzler et al., 2015).

The third theory includes the resource-based view and the knowledge-based view and focuses on the competitive edge of family businesses due to the nature and transfer of knowledge within the family (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991; Peteraf, 1993). Specifically, the interaction between family unit, business unit, and individual family members generates a unique system of distinctive and inimitable resources and capabilities (Chua, Chrisman, & Sharma, 1999; Zahra, Hayton, & Salvato, 2004), which represents an advantage for the business. These resources and capabilities relate to tacit knowledge: commitment, trust, reputation, know-how, valuable relationships, innovation talents, corporate culture and organization (Cabrera-Suárez et al., 2001; Barney & Hansen, 1994). This harmony also allows for more efficient communication, information sharing (Tagiuri & Davis, 1996) and decision-making (Gersick, Davis, Hampton, & Lansberg, 1997). Thus, management run by family members may have a positive effect on innovation (Matzler et al., 2015). Family managers also have a greater knowledge of their firms and networks, positively supporting innovation decisions (Johannisson & Huse, 2000); but non-family managers can provide new expertise, objectivity and alternative perspectives that may be overlooked by family members, and they can improve resource-allocation decisions by avoiding possible expropriation of a firm’s wealth by family members (Anderson & Reeb, 2004; Dalton, Daily, Ellstrand, & Johnson, 1998).

In the literature, the effects of different types of management within FBs on firm performance are still unclear (Cucculelli et al., 2014). More generally, some studies suggest that FBs are more innovative than non-FBs, as highlighted by Craig and Dibrell (2006) with reference to US firms, and Llach and Nordqvist (2010) for Spanish firms.

In terms of management, Matzler et al. (2015) found a positive relationship in Germany between family-managers and innovation output (patent counts and the forward citation of patents) but a negative relationship in terms of innovation input (R&D). Hansson, Liljeblom, and Martikainen (2011) found a positive effect of Family CEO on performances (ROA and ROI) in Finland, particularly when the CEO is the founder. Focusing on FBs where family members are involved in management, Nieto, Santamaria, and Fernandez (2015) found for Spanish firms a greater propensity for incremental innovation instead of radical innovation.

In the case of Italy, the issue has been analyzed from a different point of view. Sciascia and Mazzola (2008) used numerous indicators to measure performance (sales growth, revenue growth, net profit growth, return on net asset growth, reduction of debt/equity ratio, return on equity growth, and dividends growth) and found that family businesses run by family-managers perform worse. Caselli and Di Giuli (2010), using ROA and ROI, confirm this finding. Amore, Minichilli, and Corbetta (2011) found that non-family managers foster investments through an increase in debt. Regarding productivity, Bloom et al. (2008) and Bandiera, Guiso, Prat, and Sadun (2008) identified a negative effect associated with the presence of family managers. Cucculelli et al. (2014) pointed out that when considering only family-owned businesses, there is no difference - in terms of productivity - between FBs run by family managers and those run by outside managers.

In terms of innovation, Cucculelli et al. (2016) found that family management can limit the renewal of technological capabilities in products. Minetti et al. (2015) highlighted a negative relationship between product innovation and shares of external managers, as possible consequence of conflicts between shareholders and managers (for an analysis on family business and innovation from a conceptual point of view, see De Massis et al. (2015); for a systematic international review of empirical analyses, see Duran, Kammerlander, Van Essen, & Zellweger (2016). Overall, studies generally focus on product innovation without territorial considerations. Digitalization increasingly affects innovation (Evangelista, Guerrieri, & Meliciani, 2014), and policies in advanced countries are based on Industry 4.0 platforms, which promote the digital technological innovation of SMEs (Crnjac et al., 2017; Geissbauer et al., 2015; European Commission, 2017). Thus, two insights emerge from the literature: the role of management within family businesses to develop innovation activities in less developed regions, and the innovation framework of Industry 4.0 (Pickering & Byrne, 2014; for a review see Liao et al., 2017; Moeuf et al., 2018).

RESEARCH METHODS

Data

The data source is a survey carried out by Unioncamere (Italian Union of Chambers of Commerce) in early 2018. The data refer to a statistically representative sample of 3,000 small- and medium-sized Italian manufacturing firms with between 5 and 249 employees.

The dataset was enriched with structural characteristics of the firms (age, economic activities, etc.) through a record linkage to an administrative archive. The questionnaire submitted to the firms includes information about the issues of ownership and management, workforce characteristics, innovation and R&D, Industry 4.0, internationalization, and relationships.

Variables description

Dependent variable

The dependent variable concerns the innovation related to the Industry 4.0 program. Industry 4.0 can be defined as an in-depth transformation of business models involving digitalization, automation, and robotics (Gotz & Jankowska, 2017). Italy’s Industry 4.0 plan (Ministry of Economic Development, 2017) identifies nine topics: advanced manufacturing solutions; additive manufacturing; augmented reality; simulation; horizontal/vertical integration; industrial Internet; cloud; cyber security; and big data and analytics. The dependent variable (dummy) used in the regressions takes the value of 1 if the firm invested in at least one topic of Italy’s Industry 4.0 plan during the period 2017 to mid-2018. Table 1 displays the variable description.

Table 1. Variables description

|

Variables |

Type |

Description |

|

|

Dependent variable |

|||

|

Industry 4.0 |

Dummy |

whether the firm has invested in Industry 4.0 during the period 2017 to mid-2018 (yes = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

Independent variables: firm’s behavior |

|||

|

External Management |

Dummy |

whether the firm run by external manager (yes = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

R&D |

Dummy |

whether the firm invested in R&D during the period 2015-17 (yes = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

Export |

Dummy |

whether the firm exports (yes = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

IPP last |

Dummy |

whether the firm introduced some type of innovation (process/product) in 2014-2016 (yes = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

Green |

Dummy |

whether the firm invested in circular economy (energy efficiency, raw materials reuse and renewables, remanufacturing, reverse logistic, recycling and waste reduction) (yes = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

Stakehold |

Dummy |

whether the firm is no-profit maximization (si = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

Bank R |

Dummy |

whether the firm strengthened relationships with the banking system (yes = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

University R |

Dummy |

whether the firm strengthened relationships with the research centers and University (yes = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

Firm R |

Dummy |

whether the firm strengthened relationships with other firms (yes = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

HC |

Dummy |

whether the firm has employees with tertiary degrees (yes = 1. no = 0) |

|

|

Independent variables: firm’s structural characteristics |

|||

|

Age |

Continuous |

Number of years since inception (logarithm) |

|

|

Size |

Continuous |

Number of employees (logarithm) |

|

|

Pavitt sectors |

Categorical |

Sectoral Pavitt industry classification (Suppliers dominated = 1, Scale intensive = 2, Specialized suppliers = 3, Science based = 4) |

|

Family businesses and management

Family businesses are variously defined in the literature (Astrachan & Shanker, 2003; Chua et al., 1999; Miller, Le Breton-Miller, Lester, & Cannella, 2007). Chua et al. (1999) define family businesses as businesses “governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families”. Three criteria have been used to measure a family’s influence in a firm (López-Gracia & Sánchez-Andújar, 2007): capital ownership (Donckels & Lambrecht, 1999); management decision (Filbeck & Lee, 2000); and resources monitoring and provision through presence on the board (Anderson & Reeb, 2004). In this study, FBs are regarded as firms where the founder and/or family members (regardless of the generation) are the owners. From the management perspective, FBs are divided into the two categories of FBs managed by the founder and/or family members (Family management) and those managed by non-family members (External management).

Control variables: Determinants of innovation and firm’s characteristics

We consider different variables related to innovation determinants. We include R&D investments (Cuccullelli et al., 2016; Guerrieri, Luciani, & Meliciani, 2011) (a dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the firm invested in R&D and 0 otherwise) as R&D is recognized as a reasonable indicator of innovation input (Adams, Bessant, & Phelps, 2006; Barker & Mueller, 2002; Block, 2009; Chen & Hsu, 2009; O’Brien, 2003; Spithoven, Frantzen, & Clarysse, 2010). The firm accumulates essential technological and market capabilities enabling them to develop innovations through R&D.

Regional innovation policies identify the importance of internationalization. Nauwelaers and Wintjes (2003) and Tödling and Trippl (2005) highlight the need to support firms in linking to international input and output markets, achieving synergies and global visibility. Studies on FBs and innovation also consider internationalization as an important push factor for innovation (Nieto et al., 2015) because it requires continued innovation to remain competitive (Galende & De La Fuente, 2003; Veugelers & Cassiman, 1999). We, therefore, considered a dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the firm exports.

Within regional innovation systems, economic growth also depends on the integration of research into industry (Muscio, 2006) and on relationships between actors, in addition to investments in R&D (Camagni & Capello, 2013). Another aspect highlighted by the regional innovation framework (Nauwelaers & Wintjes, 2003; Tödling & Trippl, 2005; González-López, Dileo, & Losurdo, 2014; Dileo & Divella, 2016) considers the relationships of the firm with technological resources (R&D centers). Thus, we include a variable that considers whether the firm has relationships with universities and research centers. Moreover, we used another variable to capture whether the firm has relationships with other firms.

The regional innovation policy framework addresses two other themes: financial, highlighting the importance of the firm’s relationships with external resources; and human capital, highlighting the relevance of attracting and retaining highly skilled workers (Nauwelaers & Wintjes, 2003). Thus, we add into the analyses two variables: the first identifies whether the firm strengthened the relationships with the banking system, and the second indicates if the firm has employees with tertiary degrees.

A connection between Industry 4.0 and sustainable manufacturing has been identified (Stock & Seliger, 2016), so we consider whether the firm made green investments. We also control for a firm’s innovation propensity, identifying the businesses that innovated in the years before the introduction of the Industry 4.0 program. Social aspects may also affect innovation. Studies have found a positive relationship between social capital (trust, relational equity, etc.) and innovation at a firm level (Landry, Amara, & Lamari, 2000; Cook & Clifton, 2004; Cook, Clifton, & Oleaga, 2005; Cook, 2007). To capture this, we use a variable that identifies firms pursuing social sustainability (e.g., stakeholder interests) (Freeman, 1984) instead of only profit maximization.

We also controlled for different firm characteristics. In the empirical studies on innovation, age is used to take into account the firm’s level of experience and learning (Kumar & Saqib 1996). The variable used refers to years since establishment (Cucculelli et al., 2014, 2016; Matzler et al., 2015; Nieto et al., 2015). The size may be an important determinant of innovation activities (Becheikh, Landry, & Amara, 2006), although this issue is still controversial (Tsai & Wang, 2005). We thus include the number of employees as a variable (Cucculelli et al., 2014, 2016; Nieto et al., 2015; Minetti et al., 2015).

Finally, we also control for sectoral characteristics related to the technological regime (Nieto et al., 2015): we distinguish the firms by Pavitt sectoral classification (Cucculelli et al., 2016; Minetti et al., 2015) using the 2-digit activities Nace rev.2 Classification (Bogliacino & Pianta, 2016).

Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics are reported in Table 2. Family businesses make up 80% of the total sample. Around 15% of the FBs (referred to as “firms” here) are located in Southern Italy. In this area, almost 10% of businesses invested in Industry 4.0. Regarding family management, over 10% of FBs are managed by non-family members. Investments in R&D involved about one third (35.5%) of the firms, as did the exporters’ share (34.1%). Innovation activities in the past (before the introduction of Industry 4.0) were carried out by just over half of the firms (54.9%). Green investment propensity is less intensive and was relevant to 11.6% of the firms. Relationships with banks and with universities are more widespread (respectively 28.0% and 20.2%) than those between firms (9.5%). About one third (32.7%) of the firms employ graduate personnel. In almost all these cases in Southern Italy, the percentages are lower than those in the Centre-North, confirming the competitiveness gap between the two areas. The firm’s size is in general lower in Southern Italy, where the average number of employees is 22, versus 31 in the Centre-North. From the Pavitt sectors perspective, there are no significant territorial differences. The correlation matrix between independent variables (with the exception of age, sectoral, and size control variables) is reported in Tables 3 and 4. We also calculated the Variance Inflation Factor to test for multicollinearity. Values greater than 10 indicate a multicollinearity problem (Yoo et al., 2014). As all values are lower than this threshold, this is not a concern.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

|

Southern |

Centre-North |

||||

|

Mean |

S.D. |

Mean |

S.D. |

||

|

Industry 4.0 |

0.092 (0.016) |

0.290 |

0.127 (0.007) |

0.333 |

|

|

External Management |

0.127 (0.018) |

0.334 |

0.109 (0.007) |

0.312 |

|

|

R&D |

0.355 (0.026) |

0.479 |

0.437 (0.011) |

0.496 |

|

|

Export |

0.341 (0.026) |

0.475 |

0.490 (0.011) |

0.500 |

|

|

IPP last |

0.549 (0.027) |

0.498 |

0.569 (0.011) |

0.495 |

|

|

Green |

0.116 (0.017) |

0.320 |

0.132 (0.008) |

0.339 |

|

|

Stakehold |

0.630 (0.026) |

0.483 |

0.718 (0.010) |

0.450 |

|

|

Bank R |

0.280 (0.024) |

0.450 |

0.312 (0.010) |

0.463 |

|

|

University R |

0.202 (0.022) |

0.402 |

0.214 (0.009) |

0.410 |

|

|

Firm R |

0.095 (0.016) |

0.294 |

0.124 (0.007) |

0.330 |

|

|

HC |

0.327 (0.025) |

0.470 |

0.412 (0.011) |

0.492 |

|

|

Age |

32.312 (0.613) |

11.402 |

36.075 (0.283) |

12.672 |

|

|

Size |

22.291 (1.802) |

33.516 |

31.010 (0.946) |

42.406 |

|

|

Supplier dominated |

0.627 (0.026) |

0.484 |

0.572 (0.011) |

0.495 |

|

|

Scale intensive |

0.251 (0.023) |

0.434 |

0.215 (0.009) |

0.411 |

|

|

Specialized suppliers |

0.090 (0.015) |

0.286 |

0.168 (0.008) |

0.374 |

|

|

Science based |

0.032 (0.094) |

0.176 |

0.045 (0.004) |

0.208 |

|

Note: standard error in parenthesis.

Table 3. Correlation matrix: Southern

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

VIF |

||

|

1.External Management |

1.000 |

1.03 |

||||||||||

|

2.R&D |

0.097 |

1.000 |

1.29 |

|||||||||

|

3.Export |

0.110 |

0.319 |

1.000 |

1.33 |

||||||||

|

4.IPP last |

-0.020 |

0.248 |

0.113 |

1.000 |

1.14 |

|||||||

|

5.Green |

0.052 |

0.298 |

0.198 |

0.201 |

1.000 |

1.28 |

||||||

|

6.Stakehold |

0.041 |

0.119 |

0.059 |

0.076 |

0.109 |

1.000 |

1.06 |

|||||

|

7.Bank R |

0.013 |

0.088 |

0.108 |

0.178 |

0.076 |

-0.122 |

1.000 |

1.07 |

||||

|

8.University R |

0.013 |

0.287 |

0.245 |

0.153 |

0.290 |

0.043 |

0.070 |

1.000 |

1.21 |

|||

|

9.Firm R |

0.024 |

0.149 |

0.140 |

-0.022 |

0.313 |

0.004 |

0.082 |

0.204 |

1.000 |

1.15 |

||

|

10. HC |

0.012 |

0.268 |

0.422 |

0.123 |

0.192 |

0.151 |

0.018 |

0.217 |

0.131 |

1.000 |

1.29 |

|

|

Mean VIF |

1.19 |

Table 4. Correlation matrix: Centre-North

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

VIF |

||

|

1.External Management |

1.000 |

1.02 |

||||||||||

|

2.R&D |

0.034 |

1.000 |

1.25 |

|||||||||

|

3.Export |

0.024 |

0.203 |

1.000 |

1.24 |

||||||||

|

4.IPP last |

-0.005 |

0.324 |

0.136 |

1.000 |

1.19 |

|||||||

|

5.Green |

0.071 |

0.183 |

0.081 |

0.153 |

1.000 |

1.14 |

||||||

|

6.Stakehold |

0.099 |

-0.012 |

0.075 |

-0.059 |

0.069 |

1.000 |

1.04 |

|||||

|

7.Bank R |

0.012 |

0.128 |

0.074 |

0.205 |

0.089 |

-0.105 |

1.000 |

1.09 |

||||

|

8.University R |

0.055 |

0.233 |

0.192 |

0.109 |

0.265 |

0.017 |

0.204 |

1.000 |

1.23 |

|||

|

9.Firm R |

0.096 |

0.181 |

0.172 |

0.129 |

0.227 |

0.085 |

0.063 |

0.286 |

1.000 |

1.16 |

||

|

10. HC |

0.035 |

0.303 |

0.413 |

0.229 |

0.132 |

0.044 |

0.078 |

0.209 |

0.158 |

1.000 |

1.32 |

|

|

Mean VIF |

1.17 |

|||||||||||

Empirical model

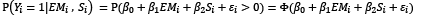

The aim of this study is to assess the impact of different types of management within family firms on the investments in Industry 4.0 in a less-developed Italian area (Southern Italy); and if there are differences with the Centre-North. As the dependent variable is binary, taking only values 1 and 0, we use probit models. Binary response models allow one to overcome the two most important disadvantages of the linear probability models: the fitted probabilities can be less than zero or greater than one; the partial effect of any independent variable is constant (Wooldridge, 2016). Our probit model is as follows:

(1)

where Yi represents the probability that the firm i invests in Industry 4.0 (Industry 4.0).

The independent variables are EMi that indicates if the family firm is run by external managers, and Si is a vector including the other independent variables relating to firm’s behaviour and characteristics. All variables are binary except for age and size. Φ is a standard normal cumulative distribution function, taking only values strictly between zero and one for all values of the parameters and the independent variables. Thus, this ensures that the estimated response probabilities are between zero and one 0 < Φ(z) <. Finally, εi is the normally distributed random error with zero mean and constant variance N(0,σ2), that captures other any unknown factors.

As probit is a non-linear model, the coefficients do not correspond to marginal effects (they indicate the change of z-values, whose effects on the probability are not linear), as in linear regressions. Thus, after estimating the probit model, we calculate marginal effects (reported in Table 5): they indicate «the effect on conditional mean of Y of a change in one regressor, say, xj » (Cameron & Trivedi 2010, p. 343). Specifically, for binary independent variables, marginal effects show how P(Y=1) changes as the independent variable changes from 0 to 1, after controlling for the other variables in the model. For categorical variables with more than two possible values, marginal effects show how P(Y=1) changes for cases in one category relative to the reference category. For continuous independent variables, marginal effects show how P(Y=1) changes as the independent variable changes by a 1-unit (Cameron & Trivedi, 2010; Williams, 2012). We used average marginal effects (AME).

Any conclusion regarding causality is limited when working on a cross-section analysis. Stata version 13 was used for all the estimates.

RESULTS

Table 5 reports the results. All regressions are based on the sample related to only family businesses by differentiating between FBs run by outside managers (External management) and those run by owner/family-members. To study the innovation factors in less-developed regions, all models focus separately on Southern Italy and on the Centre-North. We would point out that the results for the South might be less reliable than those for the Centre-North due to the much fewer observations for the former group.

After controlling for various firm characteristics and behavior, we find that external management affects the probability to invest in Industry 4.0 less significantly in Southern Italy (p<0.10) than in the Centre-North (p<0.01) (Models 1 and 2). This finding suggests that in less-developed regions family businesses require additional factors to invest in digital innovation. We, therefore, control for R&D as this is acknowledged as the main innovation input. This variable is not significant in Southern Italy, while it is significant in the Centre-North.

When we combine these two variables (Model 3), we find that in Southern Italy, the FBs run by outside managers that invest in R&D are more likely to innovate in Industry 4.0. The marginal effect of the variable External management*R&D is more significant (p<0.05; Model 3) than that related to only External management in Model 1. In Model 3, the variable External management also loses significance. This suggests that in less-developed regions family businesses require a strong injection of know-how that only an external manager can bring, as in the more developed areas. A possible lower level of management skill in Southern Italy could explain this. Furthermore, human capital has a positive and significant impact (p<0.05) on the propensity to invest in Industry 4.0 regardless of the development level of the territory.

For a robustness check, we replicate the model with the interaction (External management*R&D) for the Centre-North (Model 4) and do not find the same evidence as in the Southern case. Indeed, in the Centre-North the variable External management*R&D does not influence the likelihood to invest in Industry 4.0, while External management and R&D when considered separately confirm significant and positive marginal effects (p<0.05 in both cases).

Regarding other variables, we find that the firms that innovated in the past are significantly more likely to invest in Industry 4.0 in both areas. This may contribute to a possible increase in the innovation divide between the innovative firms that have continued to invest in innovation (in this case, digital innovation) and the non-innovative firms.

Table 5. Results

|

Southern (1) |

Centre-North (2) |

Southern (3) |

Centre-North (4) |

||

|

External Management |

0.066* (0.034) |

0.070*** (0.019) |

-0.039 (0.065) |

0.064** (0.030) |

|

|

External Management*R&D |

0.172** (0.081) |

0.011 (0.039) |

|||

|

R&D |

0.027 (0.032) |

0.039*** (0.015) |

-0.007 (0.035) |

0.038** (0.016) |

|

|

Export |

0.029 (0.033) |

0.049*** (0.016) |

0.023 (0.033) |

0.049*** (0.016) |

|

|

IPP last |

0.077** (0.033) |

0.040** (0.016) |

0.083** (0.033) |

0.040** (0.016) |

|

|

Green |

0.073** (0.036) |

0.064*** (0.018) |

0.078** (0.036) |

0.064*** (0.018) |

|

|

Stakehold |

0.126*** (0.044) |

0.029* (0.017) |

0.132*** (0.044) |

0.030* (0.017) |

|

|

Bank R |

0.006 (0.033) |

-0.005 (0.015) |

0.005 (0.033) |

-0.005 (0.015) |

|

|

University R |

-0.045 (0.037) |

0.047*** (0.016) |

-0.049 (0.037) |

0.047*** (0.016) |

|

|

Firm R |

0.031 (0.044) |

0.038** (0.019) |

0.034 (0.044) |

0.037** (0.019) |

|

|

HC |

0.063** (0.031) |

0.041** (0.017) |

0.075** (0.031) |

0.041** (0.017) |

|

|

Age |

-0.096 (0.077) |

0.023 (0.036) |

-0.090 (0.074) |

0.022 (0.036) |

|

|

Size |

0.013 (0.038) |

0.031* (0.017) |

0.001 (0.037) |

0.031* (0.017) |

|

|

Pavitt sectors |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

|

Observations |

346 |

2,009 |

346 |

2,009 |

|

|

Pseudo R2 |

0.292 |

0.156 |

0.316 |

0.156 |

Note: (a) Dependent variable: Industry 4.0. (b) The regressions are estimated by probit. (c) The table reports regressions marginal effects. (d) Standard errors are in parentheses. (e) *** p<0.01; ** p<0.05; * p<0.10.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this study, we analyze the effects of different types of management within family businesses on digital innovation - related to investments in Industry 4.0 - in less-developed Italian regions (Southern) in comparison to more developed regions (the Centre-North). Following the literature (Le Breton-Miller et al., 2011), we differentiated FBs run by family-members and those run by external managers.

The results show that in Southern Italy FBs are significantly more likely to invest in Industry 4.0 when the firm is run by an external manager and simultaneously invests in R&D. External management and R&D, when considered separately, do not affect digital innovation, as in the Centre-North. Thus, this study contributes to the literature by providing empirical evidence that the effects of external management on innovation (for the Italian case, e.g., Cucculelli et al., 2016; Minetti et al., 2015) may change according to the areas’ development levels.

Several policy implications can be drawn from our findings. Since there are different results between less and more advanced regions, innovation policies should be based on specific “innovation patterns” defined within individual regions. In line with the recent literature, policies should not just be “embedded” in the local reality, assets and skill base but also in “connectedness,” thereby guaranteeing the connection to the external environment (Camagni & Capello, 2013; Capello, 2017; McCann & Ortega-Argilés, 2015). Detailed analyses of local areas are thus very important in increasing the success of innovation policies (Hughes, 2012), because there is no single “best practice” innovation policy approach (see also Cooke et al., 2000; Isaksen, 2001; Nauwelaers & Wintjes, 2003).

Our findings also show that policies should be developed in at least two different directions: not only in terms of R&D incentives but also encouraging management openness, hence stimulating management innovation (Kraśnicka, Głód, & Wronka-Pośpiech, 2016), within family businesses. Such openness can lead to an important change in mentality in terms of firm’s innovation aimed at leveraging their full potential.

In the Industry 4.0 revolution, firms increasingly need professionals who combine organizational capabilities and digital skills in order to gain a competitive edge. Indeed, our results show that in less developed regions, R&D requires new competencies and capabilities, which may be provided by the external management, in increasing digital innovation. As highlighted in the literature, this confirms the innovation effect produced by the relationship between R&D and skills endowment (Magro, Aranguren, & Navarro, 2010; Marino & Parrotta, 2010), in self-reinforcing feedback between innovation and knowledge (Camagni & Capello, 2013). Only financial transfers, e.g., incentives for R&D, may be unsuccessful (Cobbenhagen, 1999).

All these implications confirm the importance of the “policy mix” approach (Nauwelaers, Boekholt, Mostert, Cunningham, Guy, Hofer, & Rammer, 2009; Flanagan, Uyarra, & Laranaja, 2011; OECD, 2010), hence overcoming the “linear approach” that is entirely based on R&D and technology issues. Innovation has evolved from considering science and technology as the unique drivers of innovation to also considering the organizational and social aspects, as the determinants of innovation (Magro & Wilson, 2013).

The limitations of the study have been addressed in other papers (Cucculelli et al., 2014, 2016; Matzler et al., 2015; Nieto et al., 2015; Minetti et al., 2015). The study does not distinguish management run by founders from that run by other family members, nor does it differentiate the first generation from the second or later. It does not take into account the degree of involvement of family in the management or the ownership concentration, or the foreign equity share, or if the firm is listed on the stock market. Data were not available for these factors. Balance sheet indicators were not considered as control variables (leverage, capital intensity). However, as a large proportion of the sample consists of micro and small firms, we can state that many of the abovementioned points may be less relevant. In terms of budgetary indicators, data for micro and small businesses was not available.

Integrative research could be conducted in this domain from a territorial perspective. For example, the intensity of investments in Industry 4.0, which overcomes the limitation related to the binary variable, can be investigated. Investigating whether intergenerational transfer problems may hinder innovation activities could also be of benefit.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Alessandro Rinaldi, who provided me the possibility to realize this article. I am grateful to Valentina Meliciani for her valuable suggestions on the analysis. Thanks also to Giacomo Giusti for the assistance in the construction of the database. All remaining errors are mine.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in the article are those of the author and not of the institution he is affiliated with.

References

Aas, T. H., & Breunig, K. J. (2017). Conceptualizing innovation capabilities: A contingency perspective. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 13(1), 7-24. https://doi.org/10.7341/20171311

Acs, Z. (Ed.). (2000). Regional Innovation, Knowledge and Global Change. London, United Kingdom: Pinter.

Adams, R., Bessant, J., & Phelps, R. (2006). Innovation management measurement: A review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8(1), 21-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2006.00119.x

Almada-Lobo, F. (2016). The Industry 4.0 revolution and the future of Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES). Journal of Innovation Management, 3(4), 16-21. https://doi.org/10.24840/2183-0606_003.004_0003

Amore, M. D., Minichilli, A., & Corbetta, G. (2011). How do managerial successions shape corporate financial policies in family firms?. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(4), 1016-1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2011.05.002

Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2004). Board composition: Balancing family influence in S&P 500 firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 209-237. https://doi.org/10.2307/4131472

Ang, J. S., Cole, R. A., & Lin, J. W. (2000). Agency costs and ownership structure. The Journal of Finance, 55(1), 81-106. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00201

Aronoff, C. E., & Ward, J. L. (1995). Family-owned businesses: A thing of the past or a model for the future?. Family Business Review, 8(2), 121-130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1995.00121.x

Asheim, B. T., Isaksen, A., Nauwelaers, C., & Tödtling, F. (Eds.). (2003). Regional Innovation Policy for Small-Medium Enterprises. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Astrachan, J. H., & Shanker, M. C. (2003). Family businesses’ contribution to the US economy: A closer look. Family Business Review, 16(3), 211-219. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944865030160030601

Audretsch, D. B., & Feldman, M. P. (1996). Innovative clusters and the industry life cycle. Review of Industrial Organization, 11(2), 253-273. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00157670

Autio, E. (1998). Evaluation of RTD in regional systems of innovation. European Planning Studies, 6(2), 131-140. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654319808720451

Bandiera, O., Guiso, L., Prat, A., & Sadun, R. (2008). Italian managers: Fidelity or performance. London, UK: mimeo, London School of Economics.

Bank of Italy (2009). Rapporto sulle tendenze nel sistema produttivo italiano (Questioni di Economia e Finanza No. 45). Retrieved from https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/qef/2009-0045/QEF_45.pdf

Barker III, V. L., & Mueller, G. C. (2002). CEO characteristics and firm R&D spending. Management Science, 48(6), 782-801. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.48.6.782.187

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Barney, J. B., & Hansen, M. H. (1994). Trustworthiness as a source of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 15(S1), 175-190. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150912

Bathelt, H., & Depner, H. (2003). Innovation, Institution und Region: Zur Diskussion über nationale und regionale Innovationssysteme (Innovation, institution and region: a commentary on the discussion of national and regional innovation systems). Erdkunde, 57(2), 126-143.

Becheikh, N., Landry, R., & Amara, N. (2006). Lessons from innovation empirical studies in the manufacturing sector: A systematic review of the literature from 1993–2003. Technovation, 26(5-6), 644-664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2005.06.016

Bianchi, M., Bianco, M., Giacomelli, S., Pacces, A. M., & Trento, S. (2005). Proprietà e controllo delle imprese in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Bianco, M., Bontempi, M. E., Golinelli, R., & Parigi, G. (2013). Family firms’ investments, uncertainty and opacity. Small Business Economics, 40(4), 1035-1058. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9414-3

Block, J. (2009). Long-term Orientation of Family Firms: An Investigation of R&D Investments, Downsizing Practices, and Executive Pay. Wiesbaden, Germany: Gabler Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-8412-8

Bloom, N., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2008). Measuring and explaining management practices in Italy. Rivista di Politica Economica, 98(2), 15-56.

Bogliacino, F., & Pianta, M. (2016). The Pavitt Taxonomy, revisited: Patterns of innovation in manufacturing and services. Economia Politica, 33(2), 153-180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-016-0035-1

Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2009). Some notes on institutions in evolutionary economic geography. Economic Geography, 85(2), 151-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01018.x

Braczyk, H. J., Cooke, P. N., & Heidenreich, M. (Eds.). (1998). Regional innovation systems: the role of governances in a globalized world. London, UK: UCL Press.

Bratnicka-Myśliwiec, K., Wronka-Pośpiech, M., & Ingram, T. (2019). Does socioemotional wealth matter for competitive advantage? A case of Polish family businesses. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 15(1), 123-146. https://doi.org/10.7341/20191515

Cabrera-Suárez, K., De Saá-Pérez, P., & García-Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resource‐and knowledge‐based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14(1), 37-48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2001.00037.x

Camagni, R., & Capello, R. (2013). Regional innovation patterns and the EU regional policy reform: Toward smart innovation policies. Growth and Change, 44(2), 355-389. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12012

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2010). Microeconometrics Using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Capello, R. (2017). Toward a New Conceptualization of Innovation in Space: Territorial Patterns of Innovation. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(6), 976-999. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12556

Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family–controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249-265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00081.x

Caselli, S., & Di Giuli, A. (2010). Does the CFO matter in family firms? Evidence from Italy. The European Journal of Finance, 16(5), 381-411. https://doi.org/10.1080/13518470903211657

Cassetta, E. & Pini, M. (2018). Impresa 4.0 e competitività delle medie imprese manifatturiere: Una prima analisi firm-level. Economia Marche-Journal of Applied Economics, 37(1), 35-63.

Chen, H. L., & Hsu, W. T. (2009). Family ownership, board independence, and R&D investment. Family Business Review, 22(4), 347-362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486509341062

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., De Massis, A., Frattini, F., & Wright, M. (2015). The ability and willingness paradox in family firm innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(3), 310-318. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12207

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Pearson, A. W., & Barnett, T. (2012). Family involvement, family influence, and family‐centered non‐economic goals in small firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 267-293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00407.x

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Litz, R. A. (2004). Comparing the agency costs of family and non–family firms: Conceptual issues and exploratory evidence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 335-354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00049.x

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902300402

Ciffolilli, A., & Muscio, A. (2018). Industry 4.0: National and regional comparative advantages in key enabling technologies. European Planning Studies, 26(12), 2323-2343. https://doi.org/ https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1529145

Cobbenhagen, J. (1999). Managing innovation at the company level: A study on non-sector-specific success factors. Maastricht, Netherlands: Maastricht University. Retrieved from https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/portal/files/1580911/guid-c9c6cdfc-a848-461a-94a8-d579ebceb038-ASSET2.0

Cooke, P. (2007). Social capital, embeddedness, and market interactions: An analysis of firm performance in UK regions. Review of Social Economy, 65(1), 79-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760601132170

Cook, P., & Clifton, N. (2004). Spatial variation in social capital among UK small and medium sized enterprises. Entrepreneurship and Regional Economic Development: A Spatial Perspective. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.,.

Cooke, P., Clifton, N., & Oleaga, M. (2005). Social capital, firm embeddedness and regional development. Regional Studies, 39(8), 1065-1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400500328065

Cooke, P. (2001). Regional innovation systems, clusters, and the knowledge economy. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(4), 945-974. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/10.4.945

Cooke, P. N., Boekholt, P., & Tödtling, F. (2000). The governance of innovation in Europe: regional perspectives on global competitiveness. London, UK: Pinter.

Craig, J., & Dibrell, C. (2006). The natural environment, innovation, and firm performance: A comparative study. Family Business Review, 19(4), 275-288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00075.x

Craig, J. B., & Moores, K. (2006). A 10-year longitudinal investigation of strategy, systems, and environment on innovation in family firms. Family Business Review, 19(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00056.x

Crnjac, M., Veža, I., & Banduka, N. (2017). From concept to the introduction of Industry 4.0. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 8(1), 21-30.

Cucculelli, M., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Miller, D. (2016). Product innovation, firm renewal and family governance. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(2), 90-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2016.02.001

Cucculelli, M., Mannarino, L., Pupo, V., & Ricotta, F. (2014). Owner‐management, firm age, and productivity in Italian family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(2), 325-343. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12103

Dalton, D. R., Daily, C. M., Ellstrand, A. E., & Johnson, J. L. (1998). Meta‐analytic reviews of board composition, leadership structure, and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 19(3), 269-290. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199803)19:3<269::AID-SMJ950>3.0.CO;2-K

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Tan, H. H. (2000). The trusted general manager and business unit performance: Empirical evidence of a competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 21(5), 563-576. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200005)21:5<563::AID-SMJ99>3.0.CO;2-0

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20-47. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707180258

De la Mothe, J., & Paquet, G. (1998). Local and regional systems of innovation as learning socio-economies. In Local and Regional Systems of Innovation (pp. 1-16). Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-5551-3_1

De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Pizzurno, E., & Cassia, L. (2015). Product innovation in family versus nonfamily firms: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12068

Demsetz, H. (1988). Ownership, Control and the Firm: The Organization of Economic Activity. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

Dileo, I., & Divella, M. (2016). Heterogeneity in cooperation for innovation and technological capabilities of firms in Italy. L’industria, 37(3), 493-514. https://doi.org/10.1430/85408

Dileo, I., & Pini, M. (2018). Management, digital innovation and Industry 4.0. The case of family businesses in Italy. Journal of Knowledge Management, Economics and Information Technology, VIII(6), 22-52.

Doloreux, D. (2002). What we should know about regional systems of innovation. Technology in Society, 24(3), 243-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-791X(02)00007-6

Donaldson, L., & Davis, J. H. (1991). Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management, 16(1), 49-64. https://doi.org/10.1177/031289629101600103

Donckels, R., & Lambrecht, J. (1999). The re‐emergence of family‐based enterprises in east-central Europe: What can be learned from family business research in the Western world?. Family Business Review, 12(2), 171-188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1999.00171.x

Duran, P., Kammerlander, N., Van Essen, M., & Zellweger, T. (2016). Doing more with less: Innovation input and output in family firms. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1224-1264. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0424

Edquist, C., (2005). Systems of Innovation–Perspectives and Challenges. In J. Fagerberg, D. Mowery, & R. Nelson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Innovation (pp. 181-208). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

European Commission (2017), Key lessons from national industry 4.0 policy initiatives in Europe. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/dem/monitor/sites/default/files/DTM_Policy%20initiative%20comparison%20v1.pdf

Evangelista, R., Guerrieri, P., & Meliciani, V. (2014). The economic impact of digital technologies in Europe. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 23(8), 802-824. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2014.918438

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983a). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301-325. https://doi.org/10.1086/467037

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983b). Agency problems and residual claims. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 327-349. https://doi.org/10.1086/467038

Ferri, G., Pini, M., & Scaccabarozzi, S. (2014). Le imprese familiari nel tessuto produttivo italiano: caratteristiche, dimensioni, territorialità. Rivista di Economia e Statistica del Territorio, 2, 48-77. https://doi.org/10.3280/REST2014-002003

Filbeck, G., & Lee, S. (2000). Financial management techniques in family businesses. Family Business Review, 13(3), 201-216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2000.00201.x

Flanagan, K., Uyarra, E., & Laranja, M. (2011). Reconceptualising the ‘policy mix’ for innovation. Research Policy, 40(5), 702-713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.02.005

Fornahl, D., & Brenner, T. (2003). Cooperation, Networks and Institutions in Regional Innovation Systems. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing

Fox, M. A., & Hamilton, R. T. (1994). Ownership and diversification: Agency theory or stewardship theory. Journal of Management Studies, 31(1), 69-81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1994.tb00333.x

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Marshfield, MA: Pitman Publishing.

Freeman, C. (1987). Technology and Economic Performance: Lessons from Japan. London: Printer.

Galende, J., & de la Fuente, J. M. (2003). Internal factors determining a firm’s innovative behaviour. Research Policy, 32(5), 715-736. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00082-3

Gersick, K. E., Davis, J. A., Hampton, M. M., & Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to Generation: Life Cycles of the Family Business. Harvard: Harvard Business Press.

Giacomelli, S., & Trento, S. (2005). Proprietà, controllo e trasferimenti nelle imprese italiane: Cosa è cambiato nel decennio 1993-2003? (Bank of Italy Working Papers No. 550). Retrieved from https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/temi-discussione/2005/2005-0550/tema_550.pdf

Geissbauer, R., Vedso, J., & Schrauf, S. (2016). Industry 4.0: Building the digital enterprise. Retrieved from https://www. pwc. com/gx/en/industries/industries-4.0/landing-page/industry-4.0-building-your-digital-enterprise-april-2016. pdf

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106-137. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.1.106

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Núñez -Nickel, M., & Gutierrez, I. (2001). The role of family ties in agency contracts. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 81-95. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069338

González-López, M., Dileo, I., & Losurdo, F. (2014). University-industry collaboration in the European regional context: The cases of Galicia and Apulia region. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 10(3), 57-87. https://doi.org/10.7341/20141033

Götz, M., & Jankowska, B. (2017). Clusters and Industry 4.0–do they fit together?. European Planning Studies, 25(9), 1633-1653. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1327037

Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114-135. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166664

Guerrieri, P., Luciani, M., & Meliciani, V. (2011). The determinants of investment in information and communication technologies. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 20(4), 387-403. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2010.526313

Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource‐based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1999.00001.x

Hansson, M., Liljeblom, E., & Martikainen, M. (2011). Corporate governance and profitability in family SMEs. The European Journal of Finance, 17(5-6), 391-408. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2010.543842

Hoffman, J., Hoelscher, M., & Sorenson, R. (2006). Achieving sustained competitive advantage: A family capital theory. Family Business Review, 19(2), 135-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00065.x

Hoopes, D. G., & Miller, D. (2006). Ownership preferences, competitive heterogeneity, and family-controlled businesses. Family Business Review, 19(2), 89-101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00064.x

Howells, J. (1999). Regional systems of innovation? In D. Archibugi, J. Howells, & J. Michie (Eds.), Innovation Policy in a Global Economy (pp. 67-93). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hughes, A. (2012). Choosing races and placing bets: UK national innovation policy and the globalisation of innovation systems. In D. Greenaway (Ed.), The UK in a Global World (pp. 37-70). London, UK: CEPR.

Isaksen, A. (2001). Building regional innovation systems: Is endogenous industrial development possible in the global economy?. Canadian Journal of Regional Science, 24(1), 101-120.

Jayaraman, N., Khorana, A., Nelling, E., & Covin, J. (2000). CEO founder status and firm financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 21(12), 1215-1224. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200012)21:12<1215::AID-SMJ146>3.0.CO;2-0

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360. https://doi.org/0.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

Johannisson, B., & Huse, M. (2000). Recruiting outside board members in the small family business: An ideological challenge. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 12(4), 353-378. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620050177958

Kotlar, J., De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Bianchi, M., & Fang, H. (2013). Technology acquisition in family and nonfamily firms: A longitudinal analysis of Spanish manufacturing firms. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(6), 1073-1088. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12046

Kraśnicka, T., Głód, W., & Wronka-Pośpiech, M. (2016). Management innovation and its measurement. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 12(2), 95-122. https://doi.org/10.7341/20161225

Kumar, N., & Saqib, M. (1996). Firm size, opportunities for adaptation and in-house R&D activity in developing countries: The case of Indian manufacturing. Research Policy, 25(5), 713-722. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(95)00854-3

Llach, J., & Nordqvist, M. (2010). Innovation in family and non-family businesses: A resource perspective. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 2(3-4), 381-399.

Lagendijk, A. (2000). Learning in non-core regions: Towards’ intelligent clusters’ addressing business and regional needs. In F. Boekema, K. Morgan, S. Bakkers (Eds.), Knowledge, Innovation and Economic Growth: The Theory and Practice of Learning Regions (pp. 165-191). Aldershot, UK: Edward Elgar

Landry, R., Amara, N., & Lamari, M. (2002). Does social capital determine innovation? To what extent?. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 69(7), 681-701. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-1625(01)00170-6

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world. The Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471-517. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00115

Le Breton-Miller, I., Miller, D., & Lester, R. H. (2011). Stewardship or agency? A social embeddedness reconciliation of conduct and performance in public family businesses. Organization Science, 22(3), 704-721. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0541

Le Breton–Miller, I., & Miller, D. (2006). Why do some family businesses out–compete? Governance, long–term orientations, and sustainable capability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(6), 731-746. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00147.x

Leon, R. D. (2017). Developing entrepreneurial skills. An educational and intercultural perspective. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 13(4), 97-121. https://doi.org/10.7341/20171346

Liao, Y., Deschamps, F., Loures, E. D. F. R., & Ramos, L. F. P. (2017). Past, present and future of Industry 4.0-a systematic literature review and research agenda proposal. International Journal of Production Research, 55(12), 3609-3629. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2017.1308576

López-Gracia, J., & Sánchez-Andújar, S. (2007). Financial structure of the family business: Evidence from a group of small Spanish firms. Family Business Review, 20(4), 269-287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00094.x

Lorenz, M., Ruessmann, M., Strack, R., Lueth, K. L., & Bolle, M. (2015). Man and machine in industry 4.0: How will technology transform the industrial workforce through 2025. Retrieved from https://www.bcg.com/publications/2015/technology-business-transformation-engineered-products-infrastructure-man-machine-industry-4.aspx

Lundvall, B. A. (1992). National Innovation System: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. London, UK: Pinter.

Magro, E., Aranguren, M., & Navarro, M. (2010, May). Does regional S&T policy affect firms’ behaviour. Paper presented at the Regional Studies Association annual international conference. Retrieved from http://www.regional-studies-assoc.ac.uk/events/2010/may-pecs-papers.asp

Magro, E., & Wilson, J. R. (2013). Complex innovation policy systems: Towards an evaluation mix. Research Policy, 42(9), 1647-1656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.06.005

Mandl, I. (2008). Overview of family business relevant issues. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/10389/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/pdf

Manso, G. (2011). Motivating innovation. The Journal of Finance, 66(5), 1823-1860. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01688.x

Marino, M., & Parrotta, P. (2010, June). Impacts of public funding to R&D: Evidences from Denmark. In DRUID summer conference. Retrieved from https://www.imperial.ac.uk/business-school/research/innovation-and-entrepreneurship/events/conferences/druid-summer-conference-2010/

Matzler, K., Veider, V., Hautz, J., & Stadler, C. (2015). The impact of family ownership, management, and governance on innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(3), 319-333. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12202

McCann, P., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2015). Smart specialisation, regional growth and applications to EU cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1291-1302. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.799769

Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2006). Family governance and firm performance: Agency, stewardship, and capabilities. Family Business Review, 19(1), 73-87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00063.x

Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005). Managing for the Long Run: Lessons in Competitive Advantage from Great Family Businesses. Harvard: Harvard Business Press.

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., Lester, R. H., & Cannella Jr, A. A. (2007). Are family firms really superior performers?. Journal of Corporate Finance, 13(5), 829-858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2007.03.004

Miller, D., Le Breton‐Miller, I., & Scholnick, B. (2008). Stewardship vs. stagnation: An empirical comparison of small family and non‐family businesses. Journal of Management Studies, 45(1), 51-78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00718.x

Minetti, R., Murro, P., & Paiella, M. (2015). Ownership structure, governance, and innovation. European Economic Review, 80, 165-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.09.007

Ministry of Economic Development. (2017). Italy’s plan: Industria 4.0. Retrieved from https://www.mise.gov.it/images/stories/documenti/2017_01_16-Industria_40_English.pdf

Moeuf, A., Pellerin, R., Lamouri, S., Tamayo-Giraldo, S., & Barbaray, R. (2018). The industrial management of SMEs in the era of Industry 4.0. International Journal of Production Research, 56(3), 1118-1136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2017.1372647

Moulaert, F., & Sekia, F. (2003). Territorial innovation models: A critical survey. Regional Studies, 37(3), 289-302. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340032000065442

Muscio, A. (2006). From regional innovation systems to local innovation systems: Evidence from Italian industrial districts. European Planning Studies, 14(6), 773-789. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310500496073

Mytelka, L. K. (2000). Local systems of innovation in a globalized world economy. Industry and Innovation, 7(1), 15-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/713670244

Naldi, L., Nordqvist, M., Sjöberg, K., & Wiklund, J. (2007). Entrepreneurial orientation, risk taking, and performance in family firms. Family Business Review, 20(1), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00082.x

Nauwelaers, C., Boekholt, P., Mostert, B., Cunningham, P., Guy, K., Hofer, R., & Rammer, C. (2009). Policy mixes for R&D in Europe. Retrieved from http://www.eurosfaire.prd.fr/7pc/doc/1249471847_policy_mixes_rd_ue_2009.pdf

Nauwelaers, C., & Wintjes, R. (2003). Towards a new paradigm for innovation policy. In B. T. Asheim, A. Isaksen, C. Nauwelaers, & F. Tödling (Eds.), Regional Innovation Policy for Small-medium Enterprises (pp. 193-220). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Nelson, R. R., & Rosenberg, N. (1993). Technical innovation and national systems. In R. R. Nelson (Ed.), National Innovation Systems: A Comparative Analysis (pp. 3-22). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Neubauer, F., & Lank A. G. (1998). The Family Business: Its Governance for Sustainability. New York: Routledge.

Nieto, M. J., Santamaria, L., & Fernandez, Z. (2015). Understanding the innovation behavior of family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(2), 382-399. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12075

Niosi, J., Saviotti, P., Bellon, B., & Crow, M. (1993). National systems of innovation: In search of a workable concept. Technology in Society, 15(2), 207-227. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-791X(93)90003-7

O’Brien, J. P. (2003). The capital structure implications of pursuing a strategy of innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 24(5), 415-431. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.308

OECD (2010). OECD science, technology and industry outlook 2010. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/oecd-science-technology-and-industry-outlook-2010_sti_outlook-2010-en

OECD (1999). Managing National Innovation Systems. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/industry-and-services/managing-national-innovation-systems_9789264189416-en

Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource‐based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 179-191. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140303

Pickering, C., & Byrne, J. (2014). The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(3), 534-548. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.841651

Pini, M., Dileo, I., & Cassetta, E., (2018). Digital reorganization as a driver of the export growth of Italian manufacturing small and medium sized enterprises. Journal of Applied Economic Sciences, 5(59), 1373-1385.

PWC. (2016). Industry 4.0: Building the Digital Enterprise. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/industries-4.0/landing-page/industry-4.0-building-your-digital-enterprise-april-2016.pdf

Schneider, P. (2018). Managerial challenges of Industry 4.0: An empirically backed research agenda for a nascent field. Review of Managerial Science, 12(3), 803-848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0283-2

Schulze, W. S., Lubatkin, M. H., & Dino, R. N. (2003). Toward a theory of agency and altruism in family firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(4), 473-490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00054-5

Schulze, W. S., Lubatkin, M. H., Dino, R. N., & Buchholtz, A. K. (2001). Agency relationships in family firms: Theory and evidence. Organization Science, 12(2), 99-116. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.2.99.10114

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schwab, K. (2016). The 4th industrial revolution. In World Economic Forum. New York: Crown Business.

Sciascia, S., & Mazzola, P. (2008). Family involvement in ownership and management: Exploring nonlinear effects on performance. Family Business Review, 21(4), 331-345. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944865080210040105

Sirmon, D. G., & Hitt, M. A. (2003). Managing resources: Linking unique resources, management, and wealth creation in family firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(4), 339-358. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.t01-1-00013

Smallbone, D., North, D., Roper, S., & Vickers, I. (2003). Innovation and the use of technology in manufacturing plants and SMEs: An interregional comparison. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 21(1), 37-52. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0218

Spithoven, A., Frantzen, D., & Clarysse, B. (2010). Heterogeneous firm‐level effects of knowledge exchanges on product innovation: Differences between dynamic and lagging product innovators. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27(3), 362-381. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00722.x

Stock, T., & Seliger, G. (2016). Opportunities of sustainable manufacturing in industry 4.0. Procedia Cirp, 40, 536-541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2016.01.129

Tagiuri, R., & Davis, J. (1996). Bivalent attributes of the family firm. Family Business Review, 9(2), 199-208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1996.00199.x

Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2005). One size fits all?: Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach. Research Policy, 34(8), 1203-1219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.018

Tsai, K. H., & Wang, J. C. (2005). Does R&D performance decline with firm size?—A re-examination in terms of elasticity. Research Policy, 34(6), 966-976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.05.017

Veugelers, R., & Cassiman, B. (1999). Make and buy in innovation strategies: Evidence from Belgian manufacturing firms. Research Policy, 28(1), 63-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(98)00106-1

Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2006). How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value?. Journal of Financial Economics, 80(2), 385-417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.12.005

Xu, L. D., Xu, E. L., & Li, L. (2018). Industry 4.0: State of the art and future trends. International Journal of Production Research, 56(8), 2941-2962. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2018.1444806

Westhead, P., & Howorth, C. (2007). ‘Types’ of private family firms: An exploratory conceptual and empirical analysis. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(5), 405-431. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620701552405

Williams, R. (2012). Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata Journal, 12(2), 308-331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1201200209

Wooldridge, J. M. (2016). Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.