Dr. Alex Bennet, Mountain Quest Institute, 303 Mountain Quest Lane, Marlinton, WV 24954 USA. Tel. (304) 799-7267. Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Dr. Bennet, Phi Beta Kappa, Sigma Pi Sigma, and Suma Cum Laude graduate with degrees in Physics, Mathematics, Nuclear Physics, Neuroscience and Adult Learning, Human Development, and Liberal Arts. He may be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

Embedded throughout this paper you will find the diversity of opinions that correlates to the diversity of theories, frameworks, case studies and stories that are related to the field of Knowledge Management (KM). We begin by introducing the Sampler Research Call approach and the 13 KM academics and practitioners working in different parts of the world who answered the call. We then provide baseline definitions and briefly explore the process of knowledge creation within the human mind/brain. After a brief (and vastly incomplete) introduction to KM literature at the turn of the Century, the frameworks of Sampler Call participants are introduced, and two early frameworks that achieved almost cult status—the Data-InformationKnowledge-Wisdom (DIKW) continuum and the SECI (socialization, externalization, combination and internalization) model—are explored through the eyes of Sampler Call participants. We then introduce the results of the KMTL (Knowledge Management Thought Leader) Study, which suggest theories consistent with the richness and diversity of thought interwoven throughout this paper. The field of KM is introduced as a complex adaptive system with many possibilities and opportunities. Finally, we share summary thoughts, urging us as KM academics and practitioners to find the balance between the conscious awareness/understanding of higher-order patterns and the actions we take; between the need for overarching theory and the experiential freedom necessary to address context-rich situations.

Keywords: knowledge, knowledge management, theory, information, learning, surface knowledge, shallow knowledge, deep knowledge, neuroscience, mind/brain, decision-making, higher-order patterns, complexity, thought leaders, practitioners, knowledge (proceeding), knowledge (informing), SECI model, DIKW continuum, wisdom, KM research, KM frameworks.

Introduction

When Kant proposed a Copernican Revolution, he argued that our experiences are structured by the categories of our thought, the way we think about space, time, matter, substance, causality, contingency, necessity, universality, particularity, etc. (Gardner, 1999). Bohm suggests that to achieve clarity of perception and thought “requires that we be generally aware of how our experience is shaped by ... the theories that are implicit or explicit in our general ways of thinking” (Bohm, 1980, p. 6). Bohm emphasizes that experience and knowledge are one process. It is our theories that give shape and form to experience in general, both expanding and limiting us.

The role of theory in the field of Knowledge Management (KM) is indeed controversial (Flock & Mekhilef, 2007). Some studies note that scholarly work in KM played an important role in developing the field (Serenko et al., 2012; Serenko and Bontis, 2013), and other studies point out the disparity between theory and practice (Booker et al., 2008). Many questions remain unanswered (Flock & Mekhilef, 2007). For example, can KM be seen as a discipline? If so, what are its principles, theories and models? Is there an overarching theory for KM? In this paper we explore the relationship of knowledge, theory and KM through the eyes of KM thought leaders and practitioners.

Working across domains, this paper takes a consilience approach, that is, by integrating evidence from independent sources to draw strong conclusions. Further, this exploration is intended as a thought expanding exercise which demonstrates the diversity of the field. Because of this diversity, for each opinion presented in this paper there is undoubtedly a bevy of literature to support it, and an equal amount of disagreement, with research studies often quoted as validation. It is not the intent of this paper to support or question the opinions of the contributors, but to share the different frames of reference these opinions represent. Connecting thought much like the workings of the mind/brain (which is an associative patterner), there is not a bounded literature review as such. Examples of theory or the models that represent theory, and references to supporting literature, are included in this paper.

The thought and findings from three research studies related to KM and practitioners of KM are represented in this paper. In preparation for this paper—to reflect current thought and demonstrate the diversity of opinion—a Sampler Research Call (Sampler Call) went out to KM academics and practitioners working in different parts of the world; there were 13 respondents. Two earlier research studies referenced in this paper are (1) the 2005 Knowledge Management Thought Leader (KMTL) Study which involved in-depth interviews and follow-up with 34 KM thought leaders across four continents (Bennet, 2005), and (2) the 2007 iKMS Global Survey which included responses from over 200 KM practitioners (Lambe, 2008).

Since opinions from the Sampler Call are embedded throughout this paper—including the definitions section—we introduce the Sampler Research Call approach before laying out foundational definitions and introducing concepts that help develop a common understanding of what is meant by knowledge. We then briefly look at knowledge creation from the viewpoint of the human mind/brain to explore the powerful role that theories—and the frameworks and models emerging from those theories—play in the human decision-making process. Each individual has a self-organizing, hierarchical set of theories (and consistent relationships among those theories) that guide the decision-making process (Bennet & Bennet, 2010a; 2013). We introduce representative KM literature emerging at the turn of the century with a focus on literature and frameworks forwarded by participants in the Sampler Call, then focus on two early frameworks—the Data-Information-Knowledgewisdom (DIKW) continuum and the SECI (socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization) model. These frameworks are viewed through the diverse opinions of Sampler Call participants. Finally, we look at characteristics of the KM field surfaced in the KMTL Study in conjunction with thoughts forwarded by Sampler Call participants and current examples before providing summary thoughts.

We begin.

The 2014 Sampler Research Call

An email Sampler Research Call went out to 19 geographically-dispersed Knowledge Management academics and practitioners. The intent was to hear from voices who practiced and/or taught KM in different cultures. The primary criteria were that each individual be a practitioner and/or academic in the field and have taken a leadership role through (1) publishing KM-related articles/books and/or recognized as a leader in the field, and (2) speaking at conferences and/or otherwise teaching KM. Due to the need for a short turnaround, ease of contact was also taken into account. For example, fourteen of the 19 individuals approached had participated in the 2005 KMTL Study. This previous relationship facilitated ease of contact. Nine of these participated in the Sampler Research Call.

In addition to meeting the primary criteria, the remaining 5 individuals approached were selected because of (1) their geographic location, and (2) the ease of contact, that is, a previous relationship with the editor of this JEMI special edition or with one of the authors. Four of these participated in the Sampler Call. Listed alphabetically by country, the 13 participants in the Sampler Call are: Charles Dhewa (Africa), Frada Burstein (Australia), Hubert Saint-Onge (Canada), Surinder Kumar Batra (India), Madanmohan Rao (India) Edna Pasher (Israel), Francisco Javier Carrillo (Mexico), Milton Sousa (Portugal), Dave Snowden (UK), and Nancy Dixon, Kent Greenes, Larry Prusak and Etienne Wenger-Trayner (across the US). The names and reputations of these practitioners and academics will be familiar to many readers. Short descriptions are included at the end of this paper following the authors’ bios.

Each participant was provided a copy of the call for papers that went out for this special JEMI issue. The intent of the Sampler Research Call was to “explore the connections between knowledge, KM and theory”. Each individual was asked to provide the answers as appropriate to six questions, and to provide other thoughts “of significance in regards to this focus area”. The six questions dealt with: KM practitioners trust of theoretical approaches and frameworks; why some KM frameworks (such as SECI and DIKW) had achieved cult status; favorite theories and their application; personal theories and how these personal theories serve them; authoring of papers/articles and the theories referenced in this work; and the tenuous connections in published works between KM research and KM practice.

Five of the responders chose to focus their thoughts on the relationship of knowledge, KM and theory rather than answer the specific questions; and three others left one or more questions unanswered. Thus this qualitative response was organized by related topics, with the thoughts and words attributed to these participants embedded throughout this paper. Where embedded, following each participant’s name is the reference: “(Sampler Call, 2014)”. While it is acknowledged that these are opinions that reflect a small number of academics/practitioners, a limitation of the Sampler Call approach, they demonstrate the diversity of thought related to the KM field, and the deliberate geographic spread should reduce region-specific bias. The authors do not propose to support or oppose these opinions, rather providing them for the reader’s reflection.

Foundational definitions

The terms used in this paper are explicated below in order to provide a common language within the bounds of this paper to explore the relationship of knowledge, theory, and knowledge management. Through these definitions we will see that the characteristics of knowledge in action underpin the way that knowledge management plays out in practice, specifically in the interplay between theory and practice, and the critical role of context in determining how knowledge is applied.

The brain consists of an atomic and molecular structure and the fluids that flow through this structure. The mind is the totality of the patterns in the brain created by neurons and their firings and connections. These patterns encompass all of our thoughts. The term mind/brain refers to both the structure and the patterns emerging within the structure (Bennet & Bennet, 2010).

A system is a group of elements or objects, the relationships among them, their attributes, and some boundary that allows one to distinguish whether an element is inside or outside the system. a simple system remains the same or changes very little over time. Simple systems have few states, are typically non-organic and exhibit predictable behavior. Examples are an air conditioning system, a light switch, and a calculator. While a complicated system contains a large number of interrelated parts, the connections among the parts are fixed. Complicated systems are non-organic systems in which the whole is equal to the sum of its parts, that is, they do not create emergent properties. Examples are a Boeing 777, an automobile, a computer, and an electrical power system (Bennet & Bennet, 2004).

Complexity is the condition of a system, situation, or organization that is integrated with some degree of order but has too many elements and relationships to understand in simple analytic or logical ways. a complex adaptive system (CAS) is a partially ordered system with many agents (people) that interact with each other as the system unfolds and evolves through time. They are mostly self-organizing, learning and adaptive. Examples are life, ecosystems, economies, organizations, and cultures (Axelrod and Cohen, 1999). As the term is used in this paper, this would infer a nonlinearity and unpredictability among the elements and relationships, thus the difficulty in identifying a single or “best” response or solution to a specific issue or situation.

Embracing Stonier’s description of information as a basic property of the Universe—as fundamental as matter and energy (Stonier, 1990)—we take information to be a measure of the degree of organization expressed by any non-random pattern or set of patterns. The order within a system is a reflection of the information content of the system. Data (a form of information) would then be simple patterns, and while data and information are both patterns, they have no meaning until some organism recognizes and interprets the patterns (Stonier, 1997; Bennet & Bennet, 2008b). Thus information exists in the human brain in the form of stored or expressed neuronal patterns that may be activated and reflected upon through conscious thought.

As a functional definition, knowledge is considered the capacity (potential or actual) to take effective action in varied and uncertain situations (Bennet & Bennet, 2004), a human capacity that consists of understanding, insights, meaning, intuition, creativity, judgment, and the ability to anticipate the outcome of our actions. There is considerable precedent for linking knowledge and action consistent with the emergence of the field of Knowledge Management as a business management approach in the early 1990’s driven by computing, consultants, conferences and commerce (Lambe, 2011). As detailed later in this paper, in the KMTL Study 84 percent of respondents tied knowledge directly to action or use (Bennet, 2005). Similarly, emerging from nearly 20 years of APQC’s leading research in the field of KM, O’Dell and Hubert define knowledge from the practical perspective as “information in action” (O’Dell & Hubert, 2011, p.2).

While recognizing that it is common to define information as processed data, and knowledge as actionable information, Batra (Sampler Call, 2014) finds it interesting that the definitions or interpretations of the term knowledge are contextual. However, he also notes that in another context knowledge gets interpreted as know-what, know-how, know-who and know-why, and in an HR context knowledge includes the competence set of individual skills and attitudes. Further, from a strategic perspective knowledge can be considered as a strategic resource for the firm, taking the form of intellectual capital and intangible capital. Batra finds these differences in interpretation useful to the students of KM in “appreciating that knowledge is not a monolithic entity which can be managed in a prescriptive manner.”

Dhewa (Sampler Call, 2014) likes the notion of “useful knowledge”, which he sees as a way of understanding knowledge as an economic resource, a concept expanded on by Kuznets (1955) and extensively used by Mokyr (2005) in his studies about the role of knowledge in the industrial revolution. As Dhewa suggests, “I am applying this notion in exploring the role of knowledge in the agriculture sector. Unless knowledge solves a specific issue like income growth, it’s not knowledge at all, according to me. When knowledge is applied, it defines itself.”

Linking knowledge and action provides the opportunity to measure knowledge effectiveness (Porter et al, 2003). Outside of its context and the situation in which it is being applied, knowledge itself is neither true nor false. The value of knowledge in terms of good or poor is difficult to measure other than by the outcomes of actions based on that knowledge. Good knowledge would have a high probability (closer to 1 on a 0-1 scale) of producing the desired (anticipated) outcome, and poor knowledge would have a low probability (closer to 0 or a 0-1 scale) of producing the expected result. For complex situations the quality of knowledge (from good to poor) may be hard to estimate because of the system’s unpredictability. After an outcome has occurred, it may be possible to assess the quality of knowledge by comparing the actual outcome to the expected outcome; although it is also possible that there may not be a direct observable causal relationship between a decision made/action taken and the results of that action (Bennet & Bennet, 2013).

Explicit knowledge is the descriptive term for that which can be called up from memory and described accurately in words and/or visuals (representations) such that another person can comprehend the knowledge that is expressed through this exchange of information. This is consistent with Polanyi’s description as knowledge which can be transmitted in formal systematic language (Polanyi, 1966). Explicit knowledge has historically been called declarative knowledge (Anderson, 1983). Tacit knowledge is the descriptive term for those connections among thoughts that cannot be pulled up in words, a knowing of what decision to make or how to do something that cannot be clearly voiced in a manner such that another person could extract and re-create that knowledge (understanding, meaning, etc.). Consistent with this definition, Polanyi (1966) sees tacit knowledge as personal and context-sensitive, therefore hard to communicate.

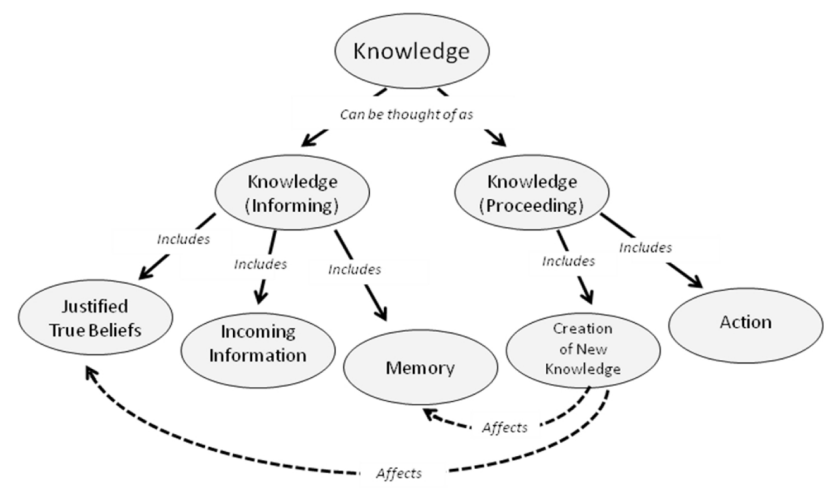

We consider knowledge as comprised of two parts: Knowledge (Informing) and Knowledge (Proceeding) (Bennet & Bennet, 2008b). This builds on the distinction made by Ryle (1949) between “knowing that” and “knowing how” (the potential and actual capacity to take effective action). Knowledge (Informing) is the information (or content) part of knowledge. While this information part of knowledge is still generically information (organized patterns), it is special because of its structure and relationships with other information. Knowledge (Informing) consists of information that may represent understanding, meaning, insights, expectations, intuition, theories and principles that support or lead to effective action. When viewed separately this is information even though it may lead to effective action. It is considered knowledge when used as part of the knowledge process. In this context, the same thought may be information in one situation and knowledge in another situation.

Knowledge (Proceeding), represents the process and action part of knowledge. It is the process of selecting and associating or applying the relevant information, or Knowledge (Informing), from which specific actions can be identified and implemented, that is, actions that result in some level of anticipated outcome. There is considerable precedent for considering knowledge as a process versus an outcome of some action. For example, Kolb (1984) forwards in his theory of experiential learning that knowledge retrieval, creation and application requires engaging knowledge as a process, not a product. Bohm reminds us that “the actuality of knowledge is a living process that is taking place right now” and that we are taking part in this process (Bohm, 1980, p. 64). Note that the process our minds use to find, create and semantically mix the information needed to take effective action is often unconscious and difficult to communicate to someone else; therefore, by definition, tacit.

In Figure 1 below, “Justified True Belief” represents the theories, values and beliefs that are generally developed over time and often tacit. “Justified True Belief” is the definition of knowledge credited to Plato and his dialogues (Fine, 2003). The concept is based on the belief that in order to know a given proposition is true you must not only believe it, but you must also have justification for believing it. Justified true belief represents an individual’s truth, that is, the beliefs and values that make up our personal theories, all developed and reinforced by personal life experiences. It is acknowledged that an individual’s justified true belief may be based on a falsehood (Gettier, 1963). However, if it is used to take effective action in terms of the user’s expectations of outcomes, then it would be considered knowledge from that individual’s viewpoint. Note that this is only one part of Knowledge (Informing), and that our beliefs and theories are part of the living process described above (Bohm, 1980; Bennet & Bennet, 2008b; 2014). The term “memory” is used as a singular collective and implies all the patterns and connections accessible by the mind occurring before the instant at hand.

Source: Alex Bennet (used with permission).

Building on the definitions of Knowledge (Informing) and Knowledge (Proceeding) introduced above, it is also useful to think about knowledge in terms of three levels: surface, shallow and deep. Recognizing any model is an artificial construct, the focus on three levels (as a continuum) is consistent with a focus on simple, complicated and complex systems (Bennet & Bennet, 2013; 2008c) and appropriate in the context of its initial use with the U.S Department of the Navy (DON), the first government organization to be named as a Most Admired Knowledge Enterprise for their extensive work in KM and organizational learning.

Surface knowledge is predominantly but not exclusively simple information (used to take effective action). Answering the question of what, when, where and who, it is primarily explicit, and represents visible choices that require minimum understanding. Surface knowledge in the form of information can be stored in books and computers. Because it has little meaning to improve recall, and few connections to other stored memories, surface knowledge is frequently difficult to remember and easy to forget (Sousa, 2006). Shallow knowledge includes information that has some depth of understanding, meaning and sense-making. To make meaning requires context, which the individual creates from mixing incoming information with their own internally-stored information, a process of creating Knowledge (Proceeding). Meaning can be created via logic, analysis, observation, reflection, and even—to some extent—prediction. Shallow knowledge is the realm of social knowledge, and as such this focus of KM overlaps with social learning theory (Bennet & Bennet, 2010b; 2007). For example, organizations that embrace the use of teams and communities facilitate the mobilization of both surface and shallow knowledge (context rich) and the creation of new ideas as individuals interact, learn and create new ideas in these groups.

For deep knowledge the decision-maker has developed and integrated many if not all of the following seven components: understanding, meaning, intuition, insight, creativity, judgment, and the ability to anticipate the outcome of our actions. Deep knowledge within a knowledge domain represents the ability to shift our frame of reference as the context and situation shift. Since Knowledge (Proceeding) must be created in order to know when and how to take effective action, the unconscious plays a large role, with much of deep knowledge tacit. This is the realm of the expert who has learned to detect patterns and evaluate their importance in anticipating the behavior of situations that are too complex for the conscious mind to understand. During the lengthy period of practice (lived experience) needed to develop deep knowledge in the domain of focus, experts have developed internal theories that guide their Knowledge (Proceeding) (Bennet & Bennet, 2008c).

Building on the definition of knowledge, learning is considered the creation of the capacity (potential or actual) to take effective action. From a neuroscience perspective, this means that learning is the identification, selection and mixing of the relevant neural patterns (information) within the learner’s mind with the information from the situation and its environment to create understanding, meaning and anticipation of the results of selection actions (Bennet & Bennet, 2008e). Each learning experience builds on its predecessor by broadening the sources of knowledge creation and the capacity to create knowledge in different ways. When an individual has deep knowledge, more and more of their learning will continuously build up in the unconscious. In other words, in the area of focus, knowledge begets knowledge. The more that is understood, the more that can be created and understood, relegating more to the unconscious to free the conscious mind to address the instant at hand. The wider the scope of application and feedback, the greater the potential to identify second order patterns, which in the largest aggregate leads to the phenomena of Big Data (MayerSchönberger & Cukier, 2013).

Descriptive definitions of Knowledge Management will be introduced below with the KMTL Study. KM thought leaders, as defined in the KMTL Study, are considered those individuals (a) whose focus has been in the area of KM for several years and continues in this or a related field, (b) who have published or edited books or multiple articles in the field, (c) who have developed and taught academic or certification courses in the area of KM, and (d) who have spoken about KM at multiple symposia and conferences (Bennet, 2005). By definition, this means that thought leaders are both learners and educators. As Durham (2004) points out, thought leadership is as much a social role as the command of knowledge, going beyond subject matter expertise to imply leadership and a willingness to assert direction.

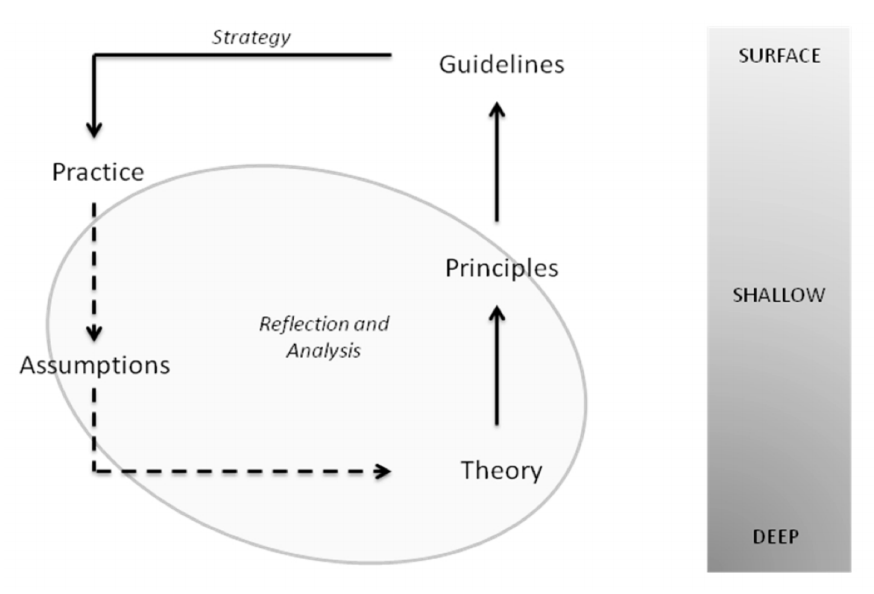

A theory is considered a set of statements and/or principles that explain a group of facts or phenomena to guide action or assist in comprehension or judgment (American Heritage Dictionary, 2006; Bennet & Bennet, 2010a). Based on beliefs and/or mental models and built on assumptions, theories provide a plausible or rational explanation of cause and effect relationships. For purposes of this paper, assumptions are something taken for granted or accepted as true without proof, a supposition or presumption. Principles are considered basic truths or laws; rules or standards; an essential quality or element. Guidelines are a statement or other indication of policy or procedure by which to determine a course of action (how to apply). a framework is a set of assumptions, concepts, values and practices that constitutes a way of viewing reality (American Heritage Dictionary, 2006). Thus a framework is tied closely to action. For purposes of this paper, it is assumed that the frameworks developed and provided by participants in the Sampler Group represent their personal theories as related to KM.

Taken from the Greek word theoria, which has the same root as theatre, theory means to see or view or to make a spectacle (Bohm, 1980). Theories reflect higher-order patterns, that is, not the facts themselves but rather the basic source of recognition and meaning of the broader patterns. Bohm sees theories as a form of insight, a way of looking at the world, clear in certain domains, and unclear beyond those domains, continuously shifting as new insights emerge through experience. While a written theory could be considered information, when understood such that it offers the potential to, or is used by, a decision-maker to create and guide effective action, it would be considered knowledge. Further, while in its incoming form it is Knowledge (Informing), when complexed with other information in the mind of the decision-maker to make decisions and guide action it becomes part of the process that is Knowledge (Proceeding). a framework or model based on a theoretical structure highlights the primary elements of the theory and their relationships.

Source: Alex Bennet (used with permission).

Batra (Sampler Call, 2014) says that the symbiotic relationship between theory and practice cannot be over-emphasized. In Figure 2 abowe, there is a dotted line between practice and assumptions and assumptions and theory. While every decision made and action taken is at some level based on the decision-maker’s assumptions, these assumptions are often tacit. Further, people tend to not dig down below surface knowledge to understand their assumptions, yet these assumptions underpin theory, from which principles can emerge. Principles drive guidelines, which in turn inform practice. Recall that a characteristic of deep knowledge is the ability to shift our frame of reference as the context and situation shift, the realm of the expert who has learned to identify and apply patterns (deep knowledge). Thus the expert is able to identify and understand second-order patterns and apply them in different situations. This is no easy task. As Fitzgerald (2003) observed, “in theory there is no difference between theory and practice; but in practice, there is.”

Decision-making as a process

It is often claimed that KM supports decision-making and innovation (e.g. Snowden, 2014; Bennet & Bennet, 2013). The decision-making process begins with a situation that is both context sensitive and situation dependent, and with three sets of information that start the learning process: (a) theories, values, beliefs, and assumptions internal to the decision-maker, (b) memories and internally-stored information patterns related to aspects of the situation at hand, and (c) incoming information from the external environment. The decision-maker creates knowledge by reflecting upon and comprehending the interactions among (a), (b) and (c) above, complexed with knowledge related to potential actions available and applicable to the situation at hand (Bennet & Bennet, 2008a). Out of this process comes understanding, meaning, insights, perhaps creative ideas, and anticipation of the outcome of potential actions, that is, knowledge, the capacity (potential or actual) to take effective action.

Frequently, there are a number of potential actions that will move the decision-maker toward the desired outcome relative to the situation at hand. For example, assuming three potential actions and their forecasted outcomes, the decision-maker evaluates each decision option in terms of the science and the art of decision-making. The science of decision-making refers to the use of logic, analysis, cost-benefit investigations, linear extrapolation, and— where feasible—simulations, trade-off analysis, and probability analysis. The art of decision-making refers to the intuition, judgment, feelings, imagination, and heuristics which come mostly from the unconscious. Combining these two approaches to understanding the forecasted outcomes, the decisionmaker selects the decision which either objectively or intuitively (or both) is expected to have the highest probability of success in achieving the desired goals and objectives, often the beginning of a decision journey. For a deeper layer of detail on complex decision-making see Bennet & Bennet (2013).

There are striking similarities between decision-making and the internal workings of the mind/brain. In the brain thoughts are represented by patterns of neuronal firings of 70 milivolt pulses and the strength of their synapse connections. The brain stores information (thoughts, images, beliefs, theories, emotions, etc.) in the form of patterns of neurons, their connections, and the strength of those connections. Although the patterns themselves are nonphysical, their existence as represented by neurons and their connections are physical, that is, composed of atoms, molecules and cells. Incoming signals to the body (images, sounds, smells, sensations of the body) are transformed into internal patterns in the mind/brain that represent (to varying degrees of fidelity) corresponding associations in the external world. The intermixing of these sets of information (patterns), what is referred to as semantic mixing (Stonier, 1997) or complexing, creates new neural patterns that represent understanding, meaning, and the anticipation of the consequences of actions (knowledge).

The mind/brain is essentially a self-organizing, cybernetic, highly complex adaptive learning system (complex adaptive system) that survives by converting incoming information from its environment into knowledge and then acts on that knowledge. This system is replete with feedback loops, control systems, sensors, memories, and meaning-making systems (theories) made up of about 100 billion neurons and about 1015 interconnections.

From the viewpoint of the mind/brain, any knowledge that is being “reused” is actually being “re-created” and—especially in an area of continuing interest—most likely complexed over and over again as incoming information is associated with internal information (Bennet & Bennet, 2009, 2006; Stonier, 1997). Thus knowledge is an emergent phenomenon. There is no direct causeand-effect relationship between information and knowledge, rather it is the interaction among many ideas, concepts and patterns of thought (including goals, objectives, beliefs, issues, context, etc.) that create knowledge. Further, if Knowledge (Informing) is different, there is a good chance that Knowledge (Proceeding) will be different, that is, the process of pulling up, integrating and sequencing associated Knowledge (Informing) and semantically complexing it with incoming information to make it comprehensible (usable and applicable) is going to vary. In essence, every time we apply Knowledge (Informing) and Knowledge (Proceeding) it is new knowledge because the human mind—unlike an information management system—unconsciously tailors what is emerging as knowledge to the situation at hand (Edelman & Tononi, 2000). Note that this is a living process occurring in the human mind/ brain. See Bennet & Bennet (2013) for an in-depth treatment of this mind/ brain process. This is a critical insight for understanding how knowledge management plays out in practice.

Early KM frameworks

In a 2011 paper citing the 2007 iKMS Global Survey, Lambe set forth a long and varied set of precedents beginning in the 1960s, focused on exploring practical and theoretical problems of knowledge transfer, utilization and diffusion (Lambe, 2011). As forwarded by Lambe, there is no doubt that— even if unacknowledged—this earlier work influenced the course of KM. Acknowledging this, a short review of KM literature begins with some representative work responding to the perceived management needs and environment of the 1990s.

Moving toward the new millennium, ideas related to the field of KM were emerging that supported every learning path, with a proliferation of theories, models, case studies and stories. For example, Butterworth Heinemann published the first annual Knowledge Management Yearbook in 1999-2000 to serve as a clearing house for new ideas (Cortada and Woods, 1999); Bukowitz and Williams (1999) produced the first KM Fieldbook focused on how to implement KM concepts and theories; Tiwana (2000) forwarded the first KM Toolkit and ASTD published an “In Action” case book on Leading Knowledge Management and Learning at the turn of the century (Phillips & Bonner, 2000). Rumizen (2002) authored The Complete Idiot’s Guide to KM in 2002, dumbing it down for practitioners; followed by Barquin, Bennet and Remez’s two volumes focused on KM in the government sector (KM: The Catalyst for Electronic Government (Barquin et al., 2003a) and Building KM Environments for Electronic Government (Barquin et al., 2003b), full of models and case studies. That same year Springer-Verlag published a two-volume Handbook on Knowledge Management (Knowledge Matters and Knowledge Directions) introducing a myriad of theory and its application (Holsapple, 2003a; 2003b).

During those early years of KM as described in this paper, the U.S. Department of Navy (DON) produced a series of KM-related toolkits that were spread by the thousands across the U.S. government sector and its supporting contractor base. The George Washington University, which had founded the first KM doctoral program and early become a partner in DON’s aggressive leadership and implementation of KM, began its persistent journey to create KM as a separate academic discipline with its own body of knowledge. Stankosky built a Knowledge Management Framework (KMF), developing overarching theoretical constructs and guiding principles, and supporting GWU Ph.D. candidates as they expanded and applied those theories and principles (Stankosky, 2005; 2011). It was Stankosky who suggested that the DON sponsor a partnering session with academia and industry associations offering KM certifications to figure out what those things were in KM that government knowledge workers wanted and needed to know. This approach defined a conceptual framework for KM through developing criteria for accredited government certification programs, defining the scope of KM for the Federal sector and laying the groundwork for successful implementation of KM in the U.S. government (Bennet & Neilson, 2003; Bennet & Bennet, 2004). The KMF is consistent with this effort.

The theories and models introduced above are a small representation of what is available today to KM practitioners. For example, each of the individuals who answered the Sampler Research Call and contributed to this paper has published and/or applied KM-related materials based on both theory and case studies. Prusak (Sampler Call, 2014) has authored many publications on KM that include some KM theories, although, true to his underlying personal theory, stories are much more prolific than theories in his books (Davenport & Prusak, 2000; Cohen & Prusak, 2001; Prusak et al., 2004; Davenport et al., 2012, and more). Dhewa (Sampler Call, 2014) works with metaphors and idioms that he says “capture various shades of knowledge.” From his unique frame of reference situated in Zimbabwe, Dhewa (2014) argues that modern science cannot meet the demands of the developing world without harnessing indigenous knowledge and then sets about applying this theory in his practice.

Rao (Sampler Call, 2014) developed a holistic framework called the “8 Cs” of KM—connectivity, content, community, culture, commerce, capacity, cooperation, capital (Rao, 2014)—which is used extensively in two of his books (Rao, 2013; 2003; 2004; Tan & Rao, 2013) and in his consulting engagements with a wide range of companies. “These days,” Rao shares, he is working on a “grand unified theory of knowledge which brings together innovation management and knowledge management” which he is combining with a search for “best practices and next practices.”

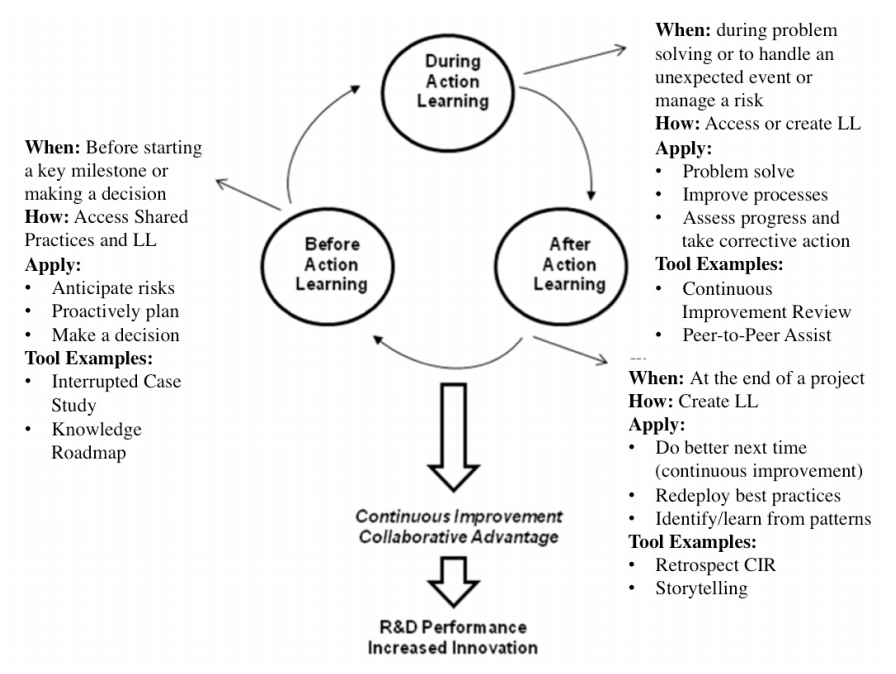

While Greenes (Sampler Call, 2014) doesn’t largely publish his work, in the early 90’s with his team at British Petroleum he had to develop frameworks that didn’t exist to assess, design and implement KM. “Over time and application (including plenty of ups and downs), I learned what works for me and the organizations I’ve enabled. To this day, I continue to evolve and renew my frameworks based on new insights from each relevant application.” Over the years Greenes has freely shared these frameworks through conferences, workshops, interviews and benchmarking studies.

Saint-Onge’s two books contain a number of frameworks (Saint-Onge & Wallace, 2003; Saint-Onge & Armstrong, 2004), as does Pasher’s book on leveraging intellectual capital (Pasher & Ronen, 2011). Focusing on the social knowledge setting, Dixon developed theory and supporting frameworks and models around organizational sensemaking and the power of conversations (Dixon, 2014; 2000; Dixon et al., 2005). Wenger-Trayner developed the theory that brought the KM field communities of practice (Wenger, 2000; Wenger et al., 2002).

Sousa (Sampler Call, 2014) has forwarded KM and ICAS-related models on innovation and leadership (Sousa, 2006; 2008; 2010). For example, Sousa says he has often used the ICAS model in lecturing and to some extent in practice as an overarching theory of a knowledge organization. Sousa refers to the extensive theory of the firm published by Bennet & Bennet (2004) developing the intelligent complex adaptive system (ICAS) model for the knowledge organization of the future. As Sousa describes, “It provides a very clear picture relating the external environment to critical organizational aspects and the emergence of an intelligent organization. People understand it conceptually (and this is the main power of the model). However, empirical evidence on the possible causal relationships outlined in the model through, for example, structural equation modeling would make it even stronger [and] having more case studies from different organizations would make it more tangible and easier to incorporate in MBA programs.”

Snowden (Snowden, 2003; Snowden & Boone, 2007), perhaps best known for his ground-breaking work in cognitive complexity (naturalizing sensemaking) and narrative, is the originator of the Cynefin Model in support of managing organizational complexity and, more recently, the designer of the SenseMaker® software suite, application of his sense-making theory which is currently employed in both government and industry to handle issues of impact measurement, narrative based KM, strategic foresight and risk management.

Burstein co-developed a task-based knowledge management (TbKM) approach that addresses the practicalities of a particular work task driven by a specific objective (Burstein & Linger, 2011). The framework focuses on pragmatic outputs and conceptual outcomes, with the two nested interrelated layers explicitly documenting knowledge work related to thinking, doing, and communication (Linder et al., 2013). As Burstein points out, “My research (and practitioner) approach to KM is based on the focus on knowledge practice, not knowledge per se.” Burstein has applied the TbKM theory to many case studies, always with success.

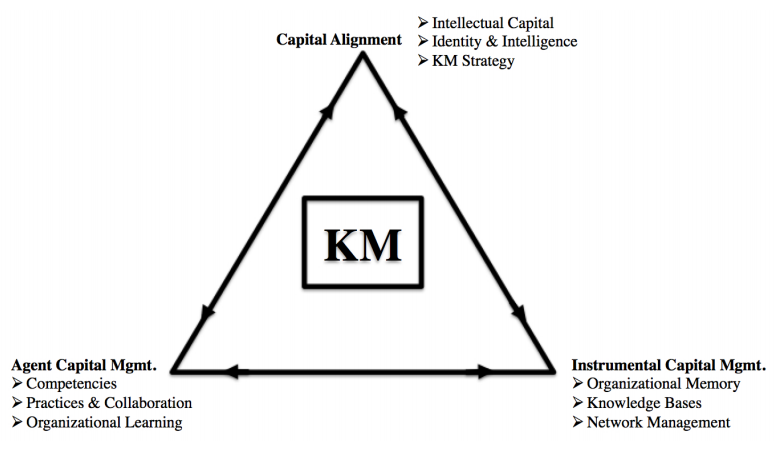

As an academic and an international consultant who actively supports application of his theories and models at the level of knowledge cities, Carrillo has developed a unified theory of value as a basis for knowledge-based development. The Knowledge-Based Value Systems (KBVS) Management Model starts by defining management and knowledge, with management the deliberate act resulting in a value increase. Knowledge is an act (process) that involves three necessary elements: an object of knowledge (that which is known), a subject of knowledge (her/him who knows) and a context of knowledge (that which determines the meaning and value of knowing. On this basis Carrillo distinguishes three core knowledge management processes. See Figure 3 below.

Source: Francisco J. Carrillo (used with permission).

Based on 23 years work at the Center for Knowledge Systems, Tecnológico de Monterrey, México, this model has been applied to assess and develop the knowledge capital base of organizations and cities, including development of a taxonomy of capital accounts for knowledge cities and the criteria for the Most Admired Knowledge City (MAKCi) international awards (Carrillo, 2002; 2004). See also Carrillo (2014). Inspired by the MAKCi framework, Batra has developed a Knowledge village Capital Framework in the context of rural habitats of India, and then adapted this to a global model that could be applied wherever substantial rural populations exist. The framework identifies seven types of capitals (identity, intelligence, relational, human, financial, material and innovation) and develops a perceptual scale to measure the degree to which a particular type of capital has been attained in a particular village or clusters of villages (Batra et al., 2013; Batra, 2007; 2012).

As Batra (Sampler Call, 2014) observes, there is a plurality of KM concepts, theoretical approaches and frameworks that have evolved over time. “In fact, there appear to be as many KM approaches and frameworks today as there are well-known KM practitioners.” This may be a KM truth.

Exploring two early KM frameworks

Two KM frameworks that came to the fore and achieved almost cult status, sometimes with very little empirical/evidential underpinning (Lambe, 2014) are the DIKW (Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom) Hierarchy (Cleveland, 1983; Zeleny, 1987; Ackoff, 1989) and the SECI (Socialization, Externalization, Internalization and Combination) Model (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). Batra (Sampler Call, 2014) says that KM frameworks such as SECI and DIKW form the backbone of KM theory and practice, attaining cult status because they provide some of the most basic concepts of KM.

As pointed out by Prusak (Sampler Call, 2014), these early models filled a vacuum left by the lack of frameworks and approaches in KM as a whole. They were pushed by consultants and academics, and strongly promoted in conferences and publications. Prusak notes that this isn’t all bad. “Even though there may not be much empirical evidence for these methods, they can spur useful conversations and sometimes even new ideas. It’s easier to discuss a method than a blank page or some random unassociated data.”

Saint-Onge (Sampler Call, 2014) recognizes these early frameworks as drawing interesting distinctions, but feels they “were not effective in serving as the foundation for the development of a knowledge strategy.” The difficulty Sousa (Sampler Call, 2014) has with these models is the lack of empirical studies to establish possible causal effects between KM interventions/models and improvements in objective organizational performance.

At an historical time when few managers grasped the concepts of complexity, Snowden (Sampler Call, 2014) feels that the quick embracing of these early theories was due to a desire for simplistic hierarchies and linear models, which was a regrettable reality. Pasher (Sampler Call, 2014) agrees. “These models belong to the same category as the IT KM solutions—the category of quick fixes which rarely achieve lasting results ... [and] feeds the cult status of SECI and DIKW.”

We explore these two early frameworks below in more detail

The DIKW Continuum. The DIKW (Data-Information-KnowledgeWisdom) continuum, an early model adopted by many practitioners in the mid-90’s, actually had its origins the previous century in the work of Harlan Cleveland entitled “Information as a resource”. In this work Cleveland changed the sequence in T.S. Eliot’s 1934 poem The Rock to read: “Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?/Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” (Cleveland, 1983).

Batra (Sampler Call, 2014) feels that “The distinction between data, information, knowledge and wisdom is the fundamental query of any student of KM.” While acknowledging that the framework is far from perfect— particularly in understanding the term wisdom in terms of the KM literature— he feels that “the DIKW hierarchy holds a prime place in the domain of KM and rightly so, despite the apparent ambiguities between various terms of the hierarchy.” Further, Batra notes that today the distinction between the terms information and knowledge is becoming blurred. “Data is now being given a prime position as a key strategic resource for business firms as compared to knowledge, since analytics, particularly big data analytics, provides the capabilities of real-time analysis of large populations of data with high volumes, velocity and variety through machine learning.” This is the development of higher-order patterns, the underpinning of theories, everchanging in a changing world as new patterns emerge.

During the 90’s, Tom Stonier, a theoretical biologist, was developing a workable theory of information, and along the way he discovered new relationships between information and the physical universe of matter and energy (Stonier, 1990; 1992; 1997) (see the earlier section on foundational definitions). Simultaneously, an intense interest in neuroscience research was spurred onward by the creation and sophistication of brain measurement instrumentation such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the electroencephalograph (EEG), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) (George, 2007; Kurzweil, 2005; Ward, 2006). For the first time we could see what was happening in the mind/brain as we process information and act on that information. Recall from our earlier discussion of decision-making in the mind/brain that there is no cause-and-effect relationship between information and knowledge; knowledge is an emergent phenomenon. It is the interaction and selection (complexing) among many ideas, concepts and patterns of thought, all consisting of information, that create knowledge.

During this same time period the body of research focused on wisdom was rapidly expanding. For example, the works of Holliday & Changler (1986); Erikson (1998), Sternberg (1990), Jarvis (1992), Kramer & Bacelar (1994), Bennett-Woods (1997), Merriam & Caffarella (1999) all take the position that wisdom is grounded in life’s rich experiences. Levitt (1999), Trumpa (1991) and Woodman & Dickinson (1996) see wisdom as a state of consciousness, with several authors linking the qualities of spaciousness, friendliness, warmth, softness and joy. These characteristics break the continuum suggested by the DIKW model. As Peter Russell explains,

Various people have pointed to the progression of data to information to knowledge ... continuing the progression suggests that something derived from knowledge leads to the emergence of a new level, what we call wisdom. But what is it that knowledge gives us that takes us beyond knowledge? Through knowledge we learn how to act in our own better interests. Will this decision lead to greater well-being, or greater suffering? What is the kindest way to respond in this situation? Wisdom reflects the values and criteria that we apply to our knowledge. Its essence is discernment. Discernment of right from wrong. Helpful from harmful. Truth from delusion. (Russell, 2007)

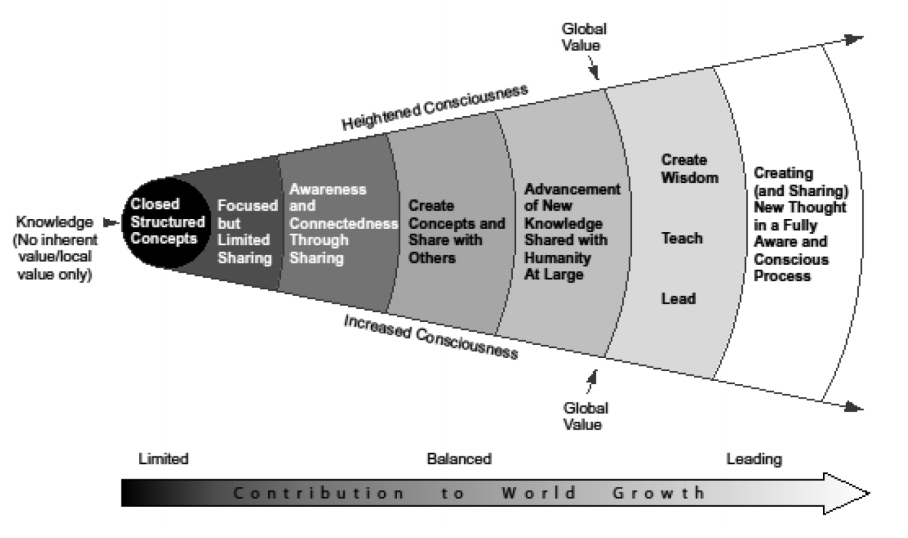

Around the turn of the century, the U.S. Department of the Navy (DON) placed knowledge at the beginning and wisdom near the end of their change model based on the seven levels of consciousness (Porter, et al, 2003; Bennet & Bennet, 2004). The change model consists of the following progression to facilitate increased connectedness and heightened consciousness: (1) closed structured concepts, (2) focused by limited sharing, (3) awareness and connectedness through sharing, (4) creating concepts and sharing these concepts with others, (5) advancement of new knowledge shared with humanity at large, (6) creating wisdom, teaching, and leading, and (7) creating (and sharing) new thought in a fully aware and conscious process. In this model, prior to reaching wisdom at level 6, there is the insertion of value (framed in the context of the greater good). Value was absent in the discussion of knowledge in support of the earlier levels of the model since the positive or negative value of knowledge is situation-dependent and context sensitive. The implication is that as knowledge sharing increases and consciousness awareness expands around the value of this focus on, and application of, knowledge theories and frameworks, there is recognition that these theories and models (higher order patterns) and what is learned from their application in a specific context may prove useful for other organizations, communities and/or cities. This is the concept of the “greater good” that moved knowledge toward wisdom. See Figure 4 below. For an in-depth treatment of this model, see Bennet & Bennet (2004)

Source: Alex Bennet (used with permission).

In a literature review of wisdom, Bennet & Bennet (2008d) clearly relate the concept of wisdom to tacit knowledge and also to the phenomenon of consciousness while acknowledging that there is something more, that is, a link between knowledge comprehension and moral development as a precursor to wisdom (Noi, et al, 2007). Costa describes this “something more”:

Wisdom is the combination of knowledge and experience, but it is more than just the sum of these parts. Wisdom involves the mind and the heart, logic and intuition, left brain and right brain, but it is more than either reason, or creativity, or both. Wisdom involves a sense of balance, an equilibrium derived from a strong, pervasive moral conviction ... the conviction and guidance provided by the obligations that flow from a profound sense of interdependence. In essence, wisdom grows through the learning of more knowledge, and the practiced experience of day-to-day life—both filtered through a code of moral conviction. [emphasis added] (Costa, 1995, p. 3)

As all of this thought and research became increasingly available to KM practitioners, they had the opportunity to carefully re-examine these early models. Snowden (Sampler Call, 2014) points out: “DIKW is ontologically and epistemologically flawed; it is not consistent with modern cognitive neuroscience or epistemology.” The early theory of a DIKW continuum was clearly the beginning of a longer conversation, one that—similar to other models used by KM practitioners—needed to integrate theories and research findings emerging from other fields of study to address its validity and usefulness to the field of KM. In other words, the framework became a catalyst for a discussion involving both theory and practice.

The SECI Model. a second theory that stands out in terms of being embraced by KM practitioners during the 1990s is the theory of organizational knowledge creation (better known as the SECI model) which describes the four modes of knowledge conversion (socialization, externalization, internalization and combination) (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). Containing both epistemological and ontological dimensions, this model focuses on how knowledge is created and how the knowledge-creation process is managed. Five enabling conditions were identified that drive the knowledge spiral (intention, autonomy, fluctuation and creative chaos, redundancy, and requisite variety) and a five-phase integrating model of the process was developed (sharing tacit knowledge, creating concepts, justifying concepts, building an archetype, and cross-leveling knowledge).

While there is a significant amount of criticism published regarding this model (Bratianu, 2014; Gourlay, 2014; Andreeva, 2014; etc.), in this paper the diverse thoughts of the Sampler Group will be offered to explore its effectiveness. For example, Dhewa, a participant in our Sampler Group, finds this model useful. “Given that knowledge is a very broad subject, KM frameworks like the SECI are very useful because they try to generalize worldviews. Without a generalized worldview, each person’s definition of knowledge will complicate conversations. KM frameworks are a critical starting point. What has made the SECI model something like a dominant force is its simplicity and focus on use of knowledge as opposed to philosophical arguments on the definition of knowledge.”

Batra (Sampler Call, 2014) thinks that the transformation taking place between tacit and explicit knowledge in any firm through the spiral of SECI is a fundamental KM concept, “without which there can be no KM.” He adds that the empirical underpinning of this framework is evident since it actually evolves out of the practices followed by a well-known Japanese company in creating new knowledge. Similarly, Batra thinks that the Buckmann Labs framework explaining the distinction between KM Infrastructure, Infostructure and Infoculture has also achieved cult status and, more recently, the framework for the MAKE (Most Admired Knowledge Enterprise), both of which are totally embedded in empirical work.

Saint-Onge (Sampler Call, 2014) found the SECI model useful in making the distinction between tacit and explicit knowledge, but said that it offered “very little guidance on how to leverage these two types of knowledge.” This led him to the conclusion that a complete theory of knowledge needed to encompass both stocks and flows. He feels that “tacit knowledge is most effectively accessed through collaboration where people are helping one another resolve real life issues.” Similar to Prusak’s earlier observation, SaintOnge believes these models served as a springboard on the discovery journey of open-minded KM practitioners.

Rao (Sampler Call, 2014) sees a long shelf life for the SECI framework, “because alot of it seems applicable from abusiness context and can be mapped on to specific activities as long as the focus is predominantly on present/past practices and not as much on innovation.” He says that most companies he has come across prefer a P-P-T framework (people, process, technology). Since “many practitioners prefer to read business books, not academic literature” he says the frameworks in the books Common Knowledge (Dixon, 2000), Working Knowledge (Davenport & Prusak, 2000) and, more recently, The New Edge in Knowledge (O’Dell & Hubert, 2011) are quite popular.

Snowden (Sampler Call, 2014) describes SECI as “a categorization model based on manufacturing case studies in a specific cultural context ... [that] have value in that context but do not, and should not, be allowed to scale.” Burstein notes that the fact that the SECI was mostly successful in Japan and in manufacturing was not communicated well in professional literature. Hence, when these and similar frameworks failed when implemented in a different context, the impact is detrimental for the level of trust practitioners have for academic models.

In more recent work, Nonaka (2012) details the concept of wise (phonetic) leadership which cites the SECI spiral as the source of innovations in any kind of organization. In this issue of the Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation appears a well-written and solidly referenced paper on how to apply the SECI model to the armed forces. The author, well-versed with the context of the military organization and with the conceptual ability to apply second-order patterns within this context, provides insights regarding the process of knowledge creation in the military setting. This paper—entitled “Knowledge creation in military organizations: How to apply the SECI model to the armed forces”—offers the opportunity for the reader to decide how well the SECI model scales to a military organization.

As with the DIKW continuum, the SECI framework has acted as a boundary object between KM theory and KM practice. Boundary objects often express or contain tensions between the communities or practices that they mediate. On the one hand it is held to have facilitated practical approaches, while on the other hand, it illuminates theoretical shortfalls.

KM theory emerging

All this theory development does not negate the fact there was a growing desire by academics and practitioners alike for some KM overarching theory (Stankosky, 2005; 2011; Lambe, 2011). As KM’s potential to help achieve individual and organizational success was recognized—with different sets of tools and processes linked to KM in different contexts and situations— there was an expanding need to train new practitioners. Yet the same characteristics that supported success in “seasoned” practitioners who could draw on previous knowledge presented barriers and difficulties for new practitioners entering the field. How to produce consistent results without consistent theories or models in the field? And from that viewpoint, what theories or models could be used to educate/train new practitioners?

Saint-Onge (Sampler Call, 2014) agrees there is nothing as useful as a well-grounded theory. “KM practitioners who do not have a framework to use as a guide for orchestrating their efforts will very likely waste a great deal of time and energy.” He adds quickly, “Of course, the framework must be based in the reality of the context in which they operate.” Saint-Onge feels that the research that has been conducted so far has thrown relatively little light on the key dynamics involved in building a vibrant, productive knowledge exchange in organizations, and is too limited in scope to provide effective guidance to KM practitioners. “We are still lacking a comprehensive framework based on systematic research.” Here, Bohm would caution that theories, as knowledge, are ever-changing forms of insight. “What prevents theoretical insights from going beyond existing limitations and changing to meet new facts is just the belief that theories give true knowledge of reality (which implies, of course, that they need never change).” (Bohm, 1980, p. 6) This would also refer to our personal theories based on justified true belief. See the earlier discussion on Knowledge (Informing).

Recognizing that KM practitioners emerge from various disciplines— the areas of work within which KM is applied—Saint-Onge points out that these disciplines tend to influence KM practitioners’ choice of theoretical approaches and frameworks. For example, economists bring theories from their discipline or sub-disciplines into KM practice. Carrillo (Sampler Call, 2014) tends to rely more on theoretical frameworks developed outside the KM field insofar as these bear more relevance to knowledge phenomena. These areas include Empirical Epistemology, Behavioral Economics, Decisionmaking, Theories of the Firm, Consciousness, Science of Science, Value Field Theory, and Development Theory. See Carrillo (2001, 2002, 2004, 2014).

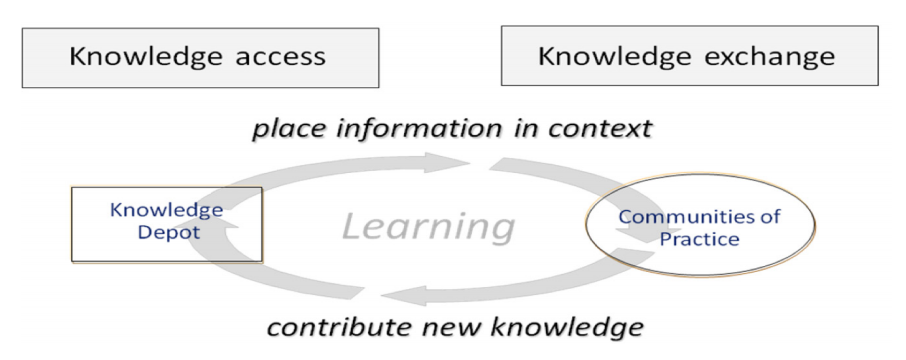

Greenes (Sampler Call, 2014) finds that theory from neuroscience, learning, behavior and other related fields impact his thinking. WengerTrayner’s social learning theory is the foundation of the KM Communities of Practice movement (Sampler Call, 2014). Visualized as a matrix approach to implementation—with KM crossing functional areas and a myriad of thought leaders emerging within the functional context of organizations—this is consistent with the results of the KMTL Study described later in this paper.

In 2007 a global survey of over 200 KM professionals sponsored by the Information and Knowledge Management Society of Singapore (iKMS)— referenced here as the iKMS Global Survey—identified the need (and desire by some practitioners) for an inter-connected theoretical base. Results from the iKMS Global Survey described KM as prone to two significant but connected implications:

“1. Lack of coherence: arising from the lack of an integrated theoretical base, and resulting in an inability to educate KM professionals effectively [and] develop a suite of substantive theory and evidence-supported practices ...

2. Poor execution: arising from poorly prepared and supported KM practitioners and low levels of continuity of personnel within KM initiatives ...” (Lambe, 2011, p. 194)

Of course, there may be other factors involved. For example, Prusak (Sampler Call, 2014) feels that KM practitioners—especially in the U.S.— distrust theory and have little interest in it. While this distrust may be the product of anti-intellectualism in the U.S. culture as a whole, Prusak thinks it is also the association of theory with wooly-minded academics who have no “real life” experiences and a subsequent lack of understanding of how organizations actually work. Snowden (Sampler Call, 2014) pushes the envelope even farther, saying that KM practitioners today are seeking security in structured roles. “They are no longer interested in why things work but just want a simplistic recipe.” Noting that too many people who have stayed in the field are pandering this approach, Snowden uses direct and colorful language to express his passion: “Then we get the complete nonsense of SharePoint, which to knowledge management is what ‘Sick Sigma’ is to innovation. KM has been dumbed down for dummies and it shows in the interests of its practitioners.”

Wenger-Trayner (Sampler Call, 2014) agrees that there may be a tendency to hang on to simple models that have intuitive appeal, and notes that this is not limited to the field of KM. “The human world is a complex system with lots of dimensions, so simple models are attractive. They can serve the purpose of organizing one’s thinking in manageable ways.” He continues that this can prove very useful, especially for people in business who need to make quick arguments about complex processes, but then cautions, “the power of simple models is also their danger ... They can become something that people apply repeatedly, almost as a substitute for thinking rather than a tool for thinking.”

Greenes (Sampler Call, 2014) says that he has been able to use a few simple self-grown frameworks to guide, tailor and align his KM approaches with his KM customers. “I deliberately keep them simple to help engage and meet non-KM experts where they are at, typically reframing them in the language of the people I’m trying to assist.” This simplicity enables him to be agile in their application. “At a high level, they fit every organization and situation. I mean, come on, how can a simple framework of five integrated elements of KM—Culture, Process, Content, Technology and Structure— not be applicable?” He adds, “I actually think it can apply to probably every discipline! It’s how you tailor what makes up each of the five elements to each organization that is each KM practitioner’s special sauce.”

Carrillo (Sampler Call, 2014) feels that most practitioners lack the background and motivation to dive into the epistemological and scientific foundations of knowledge-based events. In turn, this seems to be reciprocated by a disconnect between academic KM research and KM practice. “Although there is no lack of alternative KM frameworks,” says Carrillo, “seldom are these built on explicit scientific grounds, their knowledge claims are hardly falsifiable and rarely, if ever, are these put to rigorous scientific testing.”

In a study of KM professional groups in Australia, Booker et al. (2013) say that an outcome of the fixation with scientific rigor is that academics often develop knowledge that is of little value in practice. This research indicated that, “Few practitioners directly apply a recommendation from a research article in their practice.” (Booker et al., 2013) Further, it was found that most practitioners stay up to date on developments in their field through the KM community via online forums and groups, and that while KM practitioners are knowledgeable about books, and use tools for finding and retrieving academic articles, they prefer to talk to other KM practitioners or colleagues for day-to-day information on KM practice. Note that while this sample group was relatively small and limited to KM practitioners in Australia, there was a high level of consistency in the responses.

As a designer, advisor, speaker and attendee at conferences around the world during the latter 90’s and now well into the new century, the work of other KM practitioners was a common topic of conversation. While initially the search was for new case studies, as the years passed there was a noted repetitiveness in the focus of the presentations, that is, similar actions with similar results. While this would appear to bode well for the development of an overarching KM theory, this does not appear to be the case. These are the “recipes” described by Snowden (Sampler Call, 2014), who feels that the academic community failed KM by not engaging until there were cases to study. He says that both academics and practitioners need to get rid of their obsessions with treating KM projects as rats in a maze with a false model of causality which is contextually limited. “Practitioners need to break their dependency on recipes and start to read and study more widely and apply that learning in safe-to-fail experiments that in turn they reflect and report.” For example, Snowden is currently working in New York with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and various development experts to look at how to measure and scale success in the Development Sector. Pushing for co-evolution between theory and practice, Snowden is bringing in postdesign thinkers from MIT and biologists from the Rosen School to meet with Cognitive Edge partners to create a new science-informed approach to the problem. “We need more of that and fewer cases,” he emphasizes.

Demonstrating the diversity of thought about and approach to the field, Rao (Sampler Call, 2014) says that while practitioners may trust frameworks, they do not want to spend too much time on the philosophical or semantic aspects of KM. “They want something more practical, implementable and measurable, especially with some results demonstrable in the near term.” Prusak (Sampler Call, 2014) thinks that KM articles that are purely “words about words” without referring to any practices are mostly worthless. “KM could stand many more cases, ethological studies, maybe even autobiographies or biographies. Anything but models spun out of thin air.

While Prusak (Sampler Call, 2014) does refer to some KM theories in his work, he prefers to use theories from economics and sociology, or political theories. He admits that he has “more often used stories from the wellknown KM theorists than their theories.” Anyone who has heard Prusak speak can attest to the strength of the stories he shares. Batra (Sampler Call, 2014) notes that case studies are a combination of success stories and not so successful ones that can’t be attributed to a specific KM theory.

Saint-Onge (Sampler Call, 2014) agrees that KM research should definitely become more practice oriented. “Researchers have to collaborate with practitioners and tackle questions that are central to the development of an effective knowledge strategy in different contexts.” a scan of the theories, frameworks and publications generated by our Sampler Group shows that— complete with stories and case studies—this is exactly what is happening in this small group of KM academics and practitioners.

The KMTL study

The KMTL Study, conducted almost a decade ago, shows that the contours and dynamics of this tension and interplay between theory and practice were already emerging. The purpose of the study was to explore the aspects of KM that contributed to the passion expressed by KM thought leaders. In this section we discuss the themes that were already emerging in 2005, together with relevant insights from the 2014 Sampler Call.

The KMTL Study involved 34 KM thought leaders spanning four continents. Initial contacts were to those who appeared most often in KM literature and appeared at conferences to share their work (see the description of thought leader detailed under Definitions). Five of these recommended additional participants, who were then contacted. An overall weakness of the study is the potential for selection bias. While all individuals approached met the thought leader criteria, it was ultimately the self-selection process of their agreement to participate that drove the sample group used. All but one person approached participated; and those thought leaders interviewed later in the process continued to make suggestions of additional candidates such that time constraints became the primary limiting factor.

Three of the 34 thought leaders participated in a pilot study; and 31 in the primary stage of research. The format of the interviews was either face-to-face, a teleconference or in written format as determined by location and participant preference. The longest teleconference was four hours; the shortest two hours. Face-to-face interviews often extended through a meal. a standard open-ended format of questioning was used; with stories, anecdotes and narratives solicited beyond the answers to the questions. This qualitative approach allowed subjects to describe their own behaviors and experience in the language native to that experience. Transcripts of face-to-face and telephone interviews were reviewed by participants, and followon telephone conversations provided clarifications (Bennet, 2005). In-depth quantitative and qualitative analyses were performed.

In the KMTL Study response, Knowledge Management was seen as a perspective, a movement, a field (not a discipline) with values and value. Definitions of the field provided by 28 responders were almost as diverse as the responders themselves in terms of focus. For example, one responder said “managing the environment in which knowledge can be created, evolved, exchanged and applied into products and services that benefit a constituency” while another said, “the art of creating value by leveraging intangible assets.” Still another called it a human capability of taking a concept with some relevance into a new concept or mental model that has the potential to provide a better approach, a better solution, an improvement (Bennet, 2005). Loosely grouped in an attempt to understand their intent, eight of these definitions speak to creating/managing an environment or context; seven are more descriptive in nature, including processes that are a part of knowledge strategies; four focus more on effectiveness, improvement and value added; five focus on the concept of knowing; three see the field as a strategy; and another as an opportunity for good conceptual blending.

Similarly, while thought leaders consistently expressed a passion, an excitement about the field and the potential offered by this focus on knowledge, there was no consistency on what to call the field. In fact, 71 percent (24 out of 34) did not like the term knowledge management. Using terms that can help us define and make sense of the field, the diverse names forwarded included: knowledge awareness, connecting, ecology, emergence, environment, evolution, innovation, management, navigation, networking, sharing, strategy and transfer as well as collective intelligence, collective wisdom, competence learning, learning architecture, organizational and organizational learning. As early as 1998, Carrillo (a participant in the Sampler Call, 2014) forwarded the possibility that KM “could become a self-conscious and dynamic field of collective wisdom.” (Carrillo, 1998, p. 2). As a member of the KMTL Study population, Wiig offered that,

“Successful ‘KM’ is a mentality of how to deal with knowledge-related issues and activities, investments and the like for the purpose of promoting everything from learning to sharing but also for promoting innovation.” (Bennet, 2005, p. 106)

This response begs the question: Is it important that we use the same terminology to describe this focus on knowledge? Sousa (Sampler Call, 2014) sees KM as a fundamental organizational instrument providing meaning to the work we do, and most importantly why we do it. “Since it is through knowledge that we make sense of the world around us—and the role we and our organizations play in that world—KM becomes a strategic instrument to provide purpose to both the organization and the individual.” As a European, Sousa observes a trend towards a more hands-on consulting and change approach whereby consultants take the role of facilitator, establishing connections, making tacit knowledge explicit, tapping into unexplored areas of knowledge, raising awareness of the knowledge that exists in the organization, etc. “Interestingly, many of these consultants are not even aware of KM models or even of KM as a discipline, they just intuitively feel that this focus on knowledge flows makes sense and that change in the traditional top-down approach and expertise-based consulting (generating reports and recommendations) is not sufficient.”

Characteristics of the KM field emerging from the KMTL Study thought leader responses are introduced below. Note that these characteristics are written from the viewpoint of KM thought leaders., summarize their collective thought, and are written using the words and phrases provided by these thought leaders. For more depth on these responses, see Bennet (2005).

The field is inclusive, open minded, and encourages diversity and new ideas. KM as a field is open and inclusive, and appears to offer something for everyone. The diversity of ideas, theories and solutions emerging do not seem to be in competition with each other, rather they represent a library of possibilities available to a kaleidoscope of customers, offering the opportunity for widespread participation and contribution from many individuals, cultures, and nations. Prusak (Sampler Call, 2014) recognizes the value of this diversity of ideas. “I do strongly believe that the unit of analysis when working with knowledge is an aggregate (a network, a practice, etc., but not ‘eat all the enterprise’).” While Prusak wouldn’t call it a theory, he applies this belief to his work unceasingly and punctuates, “It works or I wouldn’t continue to use it.”

KM is self-referential, with reinforcing feedback loops. The KM field has the unusual and interesting property of being self-referential with respect to its own practitioners. The nature of the practitioner’s work and the processes involved in sharing that work with others are the same as the content of the KM field itself. All three of these involve learning, creating, sharing and applying knowledge. This self-referencing acts as a regenerative feedback loop in which the results of practitioner’s work impacts organizations and other workers which then reinforces the practitioner’s learning, knowledge, social interaction and capacity to share further work. As Pasher (Sampler Call, 2014) explains,

I never develop anything alone. I always happily collaborate with others, just as I do in this paper. I collaborate with clients and colleagues from a variety of disciplines. I look for inspiration from the sciences and the arts, from “deep smarts” and from novices. Every perspective has a contribution into creating a Life Long Learning experience for me and my clients which enables innovation and renewal [emphasis added] This is the essence of KM for me.

Greenes (Sampler Call, 2014) says that he’s blessed with a high success rate of applying his simple frameworks, which obviously reinforces his continued reliance and comfort on the frameworks he knows best. For example, in 1999 Fortune Magazine identified Greenes as the world’s leading money-maker in the field due to his business impact in British Petroleum, and under Greenes’ leadership BP won their first Most Admired Knowledge Enterprise award. Greenes acknowledges that “most of that is due to generous co-learning with the people I’ve worked with over the years (both fellow KMers and customers alike) ... and some tenacity on my part.”

Source: Hubert Saint-Onge (used with permission).