Elif Bascavusoglu-Moreau, Ph.D., Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge, The Judge Business School Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, CB2 1AG, This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Sebastian Kopera, Ph.D., Department of Management in Tourism, Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Kraków, ul. Łojasiewicza4, This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Ewa Wszendybył-Skulska, Ph.D., Department of Management in Tourism, Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Kraków, ul. Łojasiewicza 4, This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

Creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship are slogans that have become an integral part of modern tourism economy. Creativity and innovation of tourism economy as well as the meaning of creativity in tourism business are intensely discussed. Today, creativity is being frequently analyzed as a basic feature of actions performed on a daily basis in terms of both personal and professional life, a feature that every employee is required to possess. It means that employers and, above all, the education system must feel it necessary to develop certain conditions in which human creativity can be shaped, which is understood as a system that enables us to adjust to constantly changing environment and take a risk to apply new solutions to particular problems. The article aims to present the role of creativity in development of innovation in tourism as well as factors that improve it. The analytical part of the article will concentrate on the analysis of, inter alia, two significant groups of creativity determinants: factors related to availability of qualified staff on the local labor market as well as info-structure of tourism businesses.

Keywords: creativity, innovation, IT, cooperation, tourism.

Introduction: creativity and innovation

In recent years creativity has seemed to be a significant aspect in processes of initiation, realization and commercialization on the market of innovation. The expressions of innovation and creativity are mis-equated with each other. We can briefly say that creativity means an idea, whereas innovation denotes an idea including its value. Being creative is an ability to imagine things that have not existed so far. It also means searching for new solutions using new forms of labor. Creativity may stop at the level of human mind. Innovation, however, must bring a measurable effect.

This, obviously, does not mean that the two terms cancel each other. According to Altshuller, innovation is a complex phenomenon, a set of abilities, a different way of organization, synthesis and expression of knowledge, perception of the world and creation of new ideas, perspectives, reactions and products. The author sees a necessity of creative processes in innovation and stresses the relation between innovation and creativity (Altshuller, 1986, p. 6).

Creativity is a relational and context phenomenon – both its chances of forming and later demonstration as creative and innovative actions take place in interactions with other people and the context of action. In order to ensure that creative actions are taken in a great scale and result in innovations, it is necessary to have certain conditions that encourage people to think this way – “an atmosphere for creativity”, without which there is no real chance to apply innovation actions and make them last.

Therefore, creativity is a source of innovation, and its development is fostered by a proper organizational culture of an organization that should be open to any changes and new ideas of its employees, accept the right to make mistakes and become ready to take a risk related the creation of a new innovation value chain. Toyota is a perfect example of an enterprise where such culture has been successfully implemented. A model of Toyota organizational culture prefers creativity and eventually innovation that is strictly connected with the Japanese philosophy of Kaizen, focusing on an approach to continuous improvement of all processes within an organization. What is important, it applies to each member of the organization – from a manager to a front-line employee (Liker and Hoseus, 2008, p. 135). This forms the basis of the Kaizen philosophy and Toyota’s huge success was built on is a conviction that everyone has some unused skills and abilities, discovery and application of which may bring some rational profits for the company.

More and more tourist businesses realize how important an organizational culture that encourages development of creativity is. The leaders in the field are especially big businesses that are applying employee gratification programs that reward employees for their good and valuable ideas. Hunting and motivating the most skilled and developmental employees to improve their qualifications, pointing the path of development and a possibility of further education, e.g. trainings, studies or training programs at home or abroad, they all serve to develop creativity. As it may appear, small and medium-sized businesses have limited possibilities in this respect. However, their size and thereby a fewer number of employees should give supremacy in development employees creativity and hunting the most talented ones.

Literature review

Creativity of both employees and entrepreneurs translates into reaching a higher level of the new introduced innovative solutions (Table 1). Moreover, creative employees are more open to cooperation in creating and developing innovative solutions (Regional System for Innovation Support, www.rswiolsztyn.pl).

| Factors resulting from entrepreneur’s personality: | Factors related to managers’ experiences: |

|---|---|

| Creativity, Openness to innovations, Desire to differ from others, Organizational skills. |

Education in the field, Knowledge of foreign languages, Gained occupational skills, Work experience, Experience in management, Ability to organize work with people, material motivation, a need for economic success. |

| Factors related to the staff: | Factors related to direct market environment: |

| Ambitious and educated staff, Creativity, Openness to innovation, a sense of community of interest, identification with the company, Positive evaluation as for the entrepreneur, Competent organization, involvement in innovative actions, general conditions of work and gratification. |

Customers’ expectations as for innovations, Cooperation with customers, Innovation of competitive businesses, No limitations when it comes to the access to market, Situation on the labor market. |

| Factors arising from the location of tourist businesses: | Past and present results of tourist business activities: |

| Limitations from the environment protection, Necessity of cooperation with local authorities, Possibilities of cooperation with the institution of higher education or institutions of R and D configuration of the infrastructure. |

Sale value and dynamics, Financial result, Financial liquidity, Export value, Commitment to suppliers. |

| Legal and financial conditioning: | |

| Business registration law, Tax law, Conditions of taking and repaying loans, Customer authorization, Legal protection of intellectual property. |

|

| Source: Bednarczyk, Malachovsky, Wszendybył-Skulska, Strategic directions of tourism development. The cases of Poland and Slovakia. Retrieved from: www.rswi-olsztyn.pl/index.php?pokaz=189and186=186andid _menu=186. | |

Everyone is able to work creatively and solve problems. However, the man or the environment is not always able to work out a mechanism to release such abilities on a continuous basis. However, if such mechanisms are worked out, entrepreneurs’ innovative potentials of their organizations could be huge. Even if a single employee does not show great abilities except for the abilities to introduce minor, incremental innovations, the total of such actions may be impressive.

However, creativity is not the phenomenon of individuals working alone, but a social system in which actors interact and affect each other (Uzzi and Spiro, 2005, p. 448). Relations between actors facilitate the flow of information and knowledge, which has a great significance as far as stimulation of creativity is concerned (Bauer, Grether and Leach, 2002, p. 156). Employees of tourism enterprises can exchange information with each other (inside the company) or they can reach for the information and knowledge accumulated in the external environment. Because of knowledge dispersion, in order to provide the effectiveness of information processes it is necessary to link knowledge from different institutions (Kowalski, 2010, p. 11). It directs the attention of managers and owners of tourism enterprises toward information technologies, which support acquisition of knowledge from external sources (also thanks to strengthening the relationships with partners, which “opens” the access to their knowledge).

The basic function of information technologies is to enable and facilitate the handling of information streams (Lewandowski and Kopera, 2009, p. 211). When skillfully employed, they reduce the negative influence of physical distance on knowledge transfer effectiveness (Papazoglou, Ribbers, and Tsalgatidou, 2000, pp. 157–158), improve communication with environment, cause increase of knowledge exchange, improvement of learning processes, and development of new, complex interactions between individuals (Lazoi et al., 2011, p. 398-399). In this context it is worth noticing that ICTs may also influence an availability of well-qualified personnel on the local tourism market, which was demonstrated in (Kopera and Wszendybył-Skulska, 2012).

Tourism enterprises can initiate activities aimed at development of internal and external info-structure. They can also use info-structure developed by external organizations. The importance of the activities of local self-government, and public administration regarding creation of the networking environment – facilitating interactions and cooperation between enterprises, educational and research institutions, as well as self-government institutions has been discussed in: (Kopera, 2011, pp. 540–541) and (Novelli, Schmitz, and Spencer, 2006, p. 1151). The current paper will present and discuss the correlation between development of external info-structure by SMTEs (small and medium-sized tourist enterprises) (aimed at facilitation of information streams between the organization and external entities) and the creativity of their personnel.

Research methods

The results presented in the paper were gathered in the course of the multi-year research project: “Managing innovative value chains in tourism regions”. The project was aimed at identification of determinants influencing innovative activities of micro, small and medium tourism enterprises. It was assumed that innovation in the knowledge based tourism economy is achieved through application of the open innovation model, where the final result – the innovation – appears in the course of close cooperation of the main regional stakeholders. Thus, when observed from the SMTE perspective, innovation processes are determined by internal factors (innovation capabilities of tourism enterprises) as well as external factors (quality of the regional business environment, including regional cooperation platforms). All adequate factors have been identified and included in the initial research model. The presented paper refers to the factors from the internal group (creativity of the personnel and IT support applied by enterprises), as well as from the external one (availability of the well-educated staff on the local market and the quality of the tourism educational environment in tourism regions).

The initial research model has been operationalized to enable empirical research, which has been carried out using the survey method. The survey was conveyed among tourism enterprises from two neighboring voivodeships: Małopolska and Śląsk, which together form a southern region of Poland (NUTS 1). At the same time they belong to the most attractive tourist destinations in Poland. To assure comparability with the results of the previous research project, enterprises representing travel agencies and HORECA subsectors were chosen to participate in the study. Out of the whole population a random sample was drawn. Considering the structure of the population, stratified sampling was applied. The research sample contained 420 hotels, 411 restaurants and 238 travel agencies. This group was approached via mail with questionnaires. Respondents were asked to answer the questions and send the questionnaire back to the research team. Out of 1069 questionnaires sent only 60 were sent back. 5 of them were incomplete, which excluded them from further investigation. Finally, questionnaires from 55 enterprises were included in the further procedure.

The results were statistically described and analyzed. For description: frequency distribution and for correlation analysis: Pearson Chi-square and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient were applied.

Due to small number of the returned research questionnaires the results cannot be treated as representative. It means that all the statements formulated in the course of their analysis should be treated as hypotheses requiring further investigation.

Analysis

Against the background of the foregoing considerations on the importance of creativity in development of entrepreneurship in tourism, a fair interpretation of the results of the level of one of the most critical components of human capital in tourism can be made.

The results of the studies are part of much broader diagnostic analyses of the construction of an innovative value chain conducted by the Team of the Faculty of Management in Tourism at the Jagiellonian University in 2011- 2012 under the supervision of professor M. Bednarczyk.

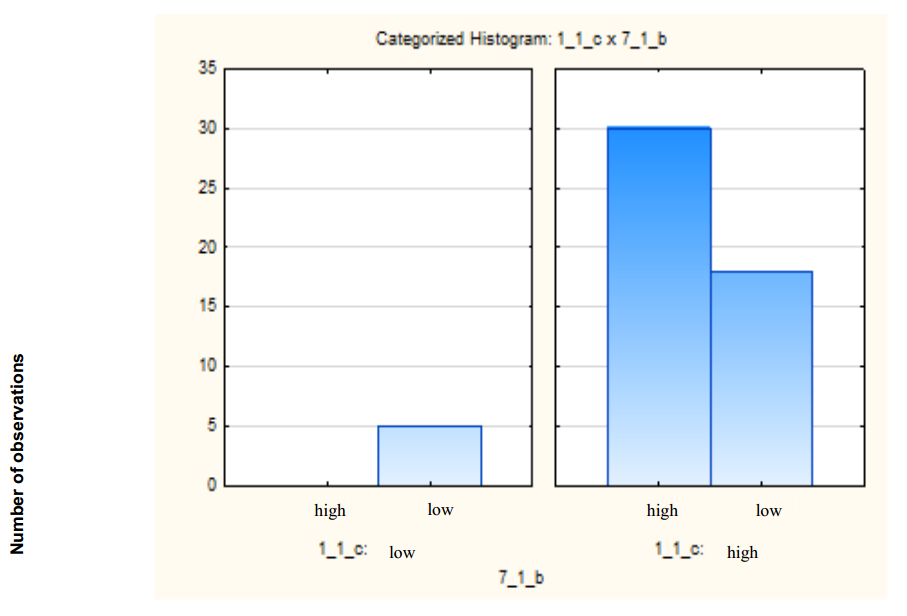

The analysis of the responses provided by the surveyed entrepreneurs showed that in most cases they evaluate creativity of their employees at the secondary level, which means that unfortunately employers’ business needs remain unmet in this field. And yet, creativity of both employers and their employees is a feature that is essential in building and developing capacity for innovations of enterprises and regions. However, the level of employees creativity is dependent on many factors, including, inter alia, the availability of skilled human resources in the market. It is evidenced by the results of the studies (χ2=7,2; p<0,00; ϕ=0,36) confirming the existence of a statistically significant relation between the level of creativity and availability of talented and creative staff in the market. Among the entrepreneurs that evaluated higher availability of creative staff, the vast majority were those who at the same time assessed the level of creativity of their employees more highly (Figure. 1). At the accepted level of significance, therefore, the occurrence of a difference between the ratings on these two aspects was confirmed, which led to the hypothesis claiming that the level of employees creativity depends on availability of creative personnel on the market. The value of chi-square statistics for the dependence of the level of employees creativity with respect to availability of creative personnel on the market shows that there are statistically significant differences (p<0.00). Higher availability of creative staff accounts for a higher level of creativity of those employed in the surveyed enterprises, as illustrated in the histogram below.

Source: Bednarczyk (2013).

In addition to the assessment of the level of employee creativity, the respondents were also asked to assess the changes that have taken place in this regard in the past three years. Unfortunately, half of the respondents claimed there have not been any significant changes in the level of employees creativity. It is highly disturbing as it may mean that there are no appropriate motivation systems to encourage employees to develop their creativity. The primary responsibility of entrepreneurs willing to develop their innovative potential should be to develop mechanisms to stimulate both the entrepreneurs and the employees to act creatively. Creativity must be developed continuously so that it could become a potential to build innovation in tourism. It is not only businesses but also schools and colleges that are responsible for it. The system of formal education that should teach and develop creativity.

In the course of the study the correlation of IT development of tourism enterprises and creativity of their personnel was also investigated. As mentioned above ICTs applied by SMTEs facilitated access to high qualified personnel on the local market. In the current study the subject of deeper investigation was the association of IT support for cooperation and collaboration with external entities in development of new products, services and knowledge applied by tourism enterprises and the level of creativity of their personnel. Based on the collected data the correlation between both factors has been proven (at p<0.05). The staff of enterprises which developed a higher level of IT support for external cooperation and collaboration was more creative than the staff of other organizations. Based on the argumentation presented earlier, it can be assumed that extensive info-structure is a factor that facilitates creativity of employees. However, using the empirical material collected in the course of the study, the causal relation cannot be unequivocally stated. For this reason the above assumption should be treated as a hypothesis that requires further investigation to be proven or rejected.

The role of education system in development of personnel creativity

The results of the presented research show that availability of creative staff received a relatively low evaluation. It is even more worrying that for many years now a number of schools for tourism industry have been growing, but instead of building more and more competitive creativity-related training programs they have been focused on mass education in accordance with the imposed standards. This inflexible approach to “mass audience” education did not contribute to creativity of young people. Hence, the assessments pointing out the low and medium-high level of creativity development in schools and colleges should not be surprising. Therefore, formal education in the regions does not contribute to creativity of human capital.

Education in the field of tourism, despite having been developed for years, needs some system changes both in Poland and Europe. L. Pender and R. Sharpley share this opinion, claiming that the tourism sector in Europe is characterized by relatively high homogeneity, but the accompanying education and training systems vary greatly due to the differences in the systems of vocational education and the status and nature of tourism in different countries and regions (Pender and Sharpley 2008, pp. 120-121). The solution to the problem is to be, as is assumed, the implementation of the European Framework of Qualifications, which will clarify all differences in recognition and validation of competences and skills in each recognizable field. Europe is becoming open not only by the abolition of borders in the strict sense, but also “opening employers’minds” on previously acquired skills seems to become a necessity (Bednarczyk, Łopacińska and Charraud 2008, p. 20).

Cooperation between science and enterprises was, inter alia, the subject of the Lisbon Strategy which resulted in a declaration defining 19 postulates concerning the rules of cooperation between colleges of higher education and enterprises in order to enhance innovation of the European economy (Runiewicz-Wardyn 2008, p. 85). One of them points to the need of a significant increase in the share of public expenditure devoted to education and identification and tackling the obstacles in the education systems that inhibit development of the innovation-friendly society, in particular, implementation of better education and skills development in innovation. The issue of cooperation between science and business was also the subject of the OECD studies which were presented in the annual reports of the organization, i.e. inter alia: “Science, Technology and Industry” (OECD Science, Technology and Industry Outlook 2012, 2012) and the seventh Framework Program (2007-2013) for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises.

The contemporary education system should, at all its levels, prepare young people to become more independent to a much greater extent than it was required in the past. First of all, the school or college should teach youngsters to solve problems on their own and to develop solution strategies, plan their own actions and organize cooperation. An important place among the required abilities is occupied by independence in searching for information as well as selecting and presenting it to others.

Conclusion

In regional coverage, educated, skilled and creative staff that represent new quality standards determine a greater innovation potential of businesses and regions conditioning the speed and direction of their development and building their competitive advantage. However, without a proper education system which is oriented towards development and enhancement of creativity among young people, it will be difficult for both entrepreneurs and whole regions to supply the expected added value in the offered products.

In search for the ways to activate creativity of the personnel of tourism enterprises one should consider the potential of information technologies in this field. Facilitation of access to highly-qualified personnel has a tremendous importance in the context of the existing human resource shortages on local tourism markets. Application of ICT to support acquisition of information from the environment is also very important for building personnel creativity. The growing sets of data, which are potentially easily available (e.g. data gathered in social media domain) require more and more sophisticated solutions for their retrieval and analysis. In this context the role of regional tourism (institutional) environment cannot be overestimated. Over 90% of tourism enterprises in the European Union are firms employing fewer than 10 people. For most of them development of any kind of IT support is impossible due to lack of necessary resources, including basic technical knowledge. For this reason institutions constituting tourism business environment, including educational and research ones, should actively engage in creation of the necessary info-structure for the transfer of knowledge and information to and in tourism sector. Such activities will result not only in the increase of the creativity of human resources in tourism, but will also enhance innovation processes in the whole tourism industry.

References

- Altshuller G.S.(1986). Find an Idea. Introduction to the Theory of Inventive Problem Solving. Novosibirsk: Nauka Publishers.

- Bednarczyk, H., Łopacińska, L., Charraud, A.M. (2008) Kształcenie zawodowe w kontekście Europejskich Ram Kwalifikacji. Radom: Państwowy Instytut Badawczy.

- Bednarczyk M., Malachovsky, A., Wszendybył-Skulska, E. (2012). Strategic directions of tourism development. The cases of Poland and Slovakia. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

- Bauer, H. H., Grether, M., Leach, M. (2002). Building customer relations over the Internet, Industrial Marketing Management, 31, 155–163.

- Bednarczyk, M. (Ed.). (2013). Managing innovative value chains in tourism regions. Reseach Report for State Funded Project (unpublished).

- Kopera, S. (2011). Rola samorządów lokalnych w budowaniu cyfrowego środowiska networkingu w regionach turystycznych. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego, nr 597, Ekonomiczne problemy usług nr 67, Drogi dochodzenia do społeczeństwa informacyjnego. Stan obecny, perspektywy rozwoju i ograniczenia (pp. 540–547). Szczecin: Uniwersytet Szczeciński.

- Kopera, S., Wszendybył-Skulska, E. (2012). Nowoczesne systemy informatyczne w turystyce a dostępność kadr na rynku lokalnym. International Journal of Management and Economics (Zeszyty Naukowe Kolegium Gospodarki Światowej SGH), 35, 172-183.

- Kowalski, A. M. (2010). Kooperacja w ramach klastrów jako czynnik zwiększania innowacyjności i konkurencyjności regionów. Gospodarka Narodowa, 5-6 (maj-czerwiec), 1–17.

- Lazoi, M., Ceci, F., Corallo, A., Secundo, G. (2011). Collaboration in an aerospace SMEs cluster: innovation and ICT dynamics. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 08(03), pp. 393–414.

- Lewandowski, J., Kopera, S. (2009). Rola nowoczesnych systemów informacyjnych w kształtowaniu zrównoważonego rozwoju gospodarki opartej na wiedzy. In. B. Poskrobko, (Ed.), Zrównoważony rozwój gospodarki opartej na wiedzy, (pp. 208–221) Wyższa Szkoła Ekonomiczna w Białymstoku, Białystok.

- Liker, J. K., Hoseus, M. (2008). Toyota culture: The heart and soul of the Toyota way. New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 135

- Novelli, M., Schmitz, B., Spencer, T. (2006). Networks, clusters and innovation in tourism: A UK experience. Tourism Management, 27(6), 1141–1152.

- OECD Science, Technology and Industry Outlook 2012. (2012). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/sti_outlook-2012-en.

- Papazoglou, M. P., Ribbers, P., Tsalgatidou, A. (2000). Integrated value chains and their implications from a business and technology standpoint. Decision Support Systems, 29(4), 323–342.

- Pender L. Sharpley R. (2008). Zarządzanie Turystyką. Warszawa: Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne, 120-121.

- Regional System for Innovation Support. (n.d.). Factors determinig innovativeness of small and medium enterprises. Retrieved from http://www.rswi-olsztyn.pl/.

- Runiewicz-Wardyn M. (2008). Knowledge Based Economy. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Akademickie, p. 85

- Uzzi, B., Spiro, J. (2005). Collaboration and creativity: TheSmall world problem. American Journal of Sociology, 111(2), 447–504.