Marlena A. Bednarska, Ph.D., Poznan University of Economics, al. Niepodleglości 10, 61-875 Poznań, Poland. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Marcin Olszewski, Ph.D., Poznan University of Economics, al. Niepodleglości 10, 61-875 Poznań, Poland. marcin. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

The success of tacit knowledge management lies in frms’ capabilites to atract and retain employees possessing unique knowledge. The purpose of the paper is to investgate students’ attudes towards career in tourism in the context of tacit knowledge management. The study was conducted on the group of 345 undergraduates and graduates enrolled in tourism and hospitality studies in Poznan. Research revealed that majority of students plan short-term career in tourism, which entails tacit knowledge leakage outside the tourism industry. It was also found that students’ attudes towards tourism careers are signifcantly influenced by previous work experience and satsfacton with the studies.

Keywords: tacit knowledge, management, attudes, career, tourism industry, students.

Introducton

Knowledge is becoming widely recognized as an important asset for gaining sustainable compettve advantage (Davenport and Prusak, 1998; Argot and Ingram, 2000), especially in the long term (Gallupe, 2001). According to Nonaka (1991, p. 96) “in an economy where the only certainty is uncertainty, the one sure source of lastng compettve advantage is knowledge”. It is crucial how organizatons create, acquire, disseminate and use knowledge, and how organizatons protect and manage the knowledge they have (Gallupe, 2001).

According to Cooper capturing the tacit knowledge in the tourism industry is one of the major challenges and to date this has not been formally addressed by researchers (2006). Tacit knowledge in the form of skills, knowhow and competences, due to duplicaton and transfer difcultes, is the most important reason for sustaining and enhancing the compettve positon of frms (Ambrosini and Bowman, 2008; da Silva, 2012). Tacit knowledge is gained and shared through practce and observaton and without the exchange of key personnel it is almost non-transferable (Nonaka, Toyama, and Nagata, 2000). It follows that the acquisiton of tacit knowledge requires offering working conditons which will atract and retain workers. Due to signifcant role of young employees in the tourism industry, it is important to determine the possibilites of acquiring workers entering the labour market by examining students’ attudes towards a career in tourism. Findings of similar research carried out in Europe, Asia, America, and Australia clearly demonstrate that for many tourism and hospitality graduates tourism jobs are short-lived professions. (Kusluvan and Kusluvan, 2000; Barron, Maxwell, Broadbridge and Ogden, 2007; Roney and Ӧztn, 2007; Dickerson, 2009; Jiang and Tribe, 2009; Richardson, 2010). It would be of value to examine this phenomenon in the Polish context.

The purpose of this paper is to investgate students’ attudes towards career in tourism and to indicate the implicatons of these attudes for tacit knowledge management. The paper opens by reviewing the literature on the role of tacit knowledge in the tourism market. Then the fndings of the study on the students’ percepton of the atractveness of career in tourism and its determinants are presented. Finally, the overall implicatons and recommendatons for future research are proposed and the main conclusions are summarised.

Tacit knowledge as a strategic asset – literature review

Knowledge is regarded as one of the most important assets for creatng and sustaining compettve advantage of the modern enterprises. The focus on resources that are developed within the organizaton and difcult to imitate puts organizatonal knowledge in a preeminent positon as the principal source of compettve advantage (Argot and Ingram, 2000). Knowledge has been variously defned: as “justfed true belief” (Nonaka, 1994, p. 15) or “mixture of framed experience, values, contextual informaton, and expert insight” (Davenport and Prusak, 1998, p. 5). Knowledge involves human actons and decisions representng interpretaton and applicaton of data (Droege and Hoobler, 2003). As data are interpreted and applied, new knowledge is ofen developed (Baumard, 1999).

The traditonal startng point for analysing knowledge is Polanyi’s (1966) distncton between codifed and tacit knowledge. Codifed knowledge is artculated knowledge, which can be specifed verbally or in writng such as patents, drawings, concepts or formulas. This feature accounts for its easy and wide disseminaton, therefore codifed knowledge is less unique to the knowledge holder in terms of creatng compettve advantage. In the current era of globalizaton, everyone has relatvely easy access to codifed knowledge (da Silva, 2012). This kind of knowledge can be exchanged among individuals and organizatons in a formalized and relatvely simple way (in writng or by using symbols and codes such as block diagrams).

Tacit knowledge, in contrast, is less easily replicated (Leonard and Sensiper, 1998). It exists in the background of consciousness, which Polanyi expressed as “we can know more than we can tell”. Leonard and Sensiper (1998, p. 114) added that “we can ofen know more than we realise”. Despite its key role in organizaton performance, the management of tacit knowledge is stll challenging to organizatons (Ambrosini and Bowman, 2008). This is due to the tacit knowledge characteristcs. According to Zack (1999, p. 46) tacit knowledge is “subconsciously understood and applied, difcult to artculate, developed from direct experience, and usually shared through highly interactve conversaton, storytelling, and shared experience”. It is included in the individual experience and involves personal beliefs, attudes, values and intuiton. People that possess tacit knowledge cannot readily explain the decision rules that underlie their performance (Polanyi, 1966). Tacit knowledge is highly personal and difcult to formalize, making it difcult to communicate. Summing up, tacit knowledge is a resource that can provide sustainable compettve advantage as it meets all the criteria of the resource-based view of the frm: it is valuable, rare, imperfectly substtutable and imitable (Barney, 1991). In the tourism industry the tacit knowledge is partcularly valuable because of the nature of the service product, where the service delivery occurs as a result of interacton between customers and employees and where it is required that employees are knowledgeable of customers’ needs in order to achieve customer satsfacton (Hallin and Marnburg, 2008).

At least four types of tacit knowledge can be identfed in literature: embrained, embodied, encultured, and embedded (Blackler, 1995):

- Embrained knowledge is dependent on conceptual skills and cognitve abilites, it allows recogniton of underlying paterns, and reflecton on these.

- Embodied knowledge is acton oriented and called ‚knowledge how’. This knowledge is acquired by doing, and is rooted in specifc contexts. This kind of knowledge may include learning from observaton or partcipaton in the service process.

- Encultured knowledge refers to the process of achieving shared understandings. Cultural meaning systems are intmately related to the processes of socializaton and acculturaton; such understandings are likely to depend heavily on language, and hence to be socially constructed and open to negotaton.

- Embedded knowledge resides in systemic routnes. The noton of ‚embeddedness’ was introduced by Granoveter (1985), who proposed a theory of economic acton that would neither be heavily dependent on the noton of culture (i.e. be ‚oversocialized’) nor heavily dependent on theories of the market (i.e. be ‚under-socialized’). His idea was that economic behaviour is intmately related to social and insttutonal arrangements.

The complex nature of valuable tacit knowledge makes its acquisiton very difcult (Kogut and Zander, 1992) as it is embodied in organizatonal members, tools, tasks and networks. Moreover, “tacit knowledge cannot be captured, translated, or converted, but only manifested, in what we do” (Tsoukas, 2003, p. 426). Thus, this kind of knowledge can be acquired only through hands-on experience or learning-by-doing (Almeida and Kogut, 1999; Zucker, Darby and Armstrong, 1998; Filatotchev, Liu, Lu and Wright, 2011). For instance, in hotel organizatons, a major part of frontline personnel’s domain-specifc knowledge is developed due to their interactons with guests, managers, colleagues, suppliers, employees of competng hotels and other external interest groups on a regular basis (Hallin and Marnburg, 2008). The tacit knowledge can be effectvely transferred through human mobility (Kaj, Pekka and Hannu, 2003; Song, Almeida and Wu, 2003; Filatotchev et al., 2011). Thus, it is more apt to be lost through employee turnover, when employees leave, companies lose not only human capital, but also accumulated knowledge (Droege and Hoobler, 2003). Companies seeking to acquire tacit knowledge must have the ability to atract human capital, and retenton of the tacit knowledge embedded in employees’ mind requires offering atractve working conditons.

The possibilites of atractng and retaining suitable employees who are holders of tacit knowledge in tourism stem from the image of the industry held by hospitality and tourism students. The literature on the atractveness of tourism job atributes contrasts negatve and positve characteristcs. Among its positves are glamour, the opportunity to travel, meetng people, foreign language use, and task variety, good atmosphere and co-operaton with colleagues, as well as prospects for internatonally based careers (Szivas, Riley and Airey, 2003; Hjalager, 2003). The negatves include unfavourable remuneraton level, limited promoton opportunites, low social status, unfavourable physical working environment, incompetency of management, and poor treatment by supervisory staff (Jiang and Tribe, 2009; Kusluvan and Kusluvan, 2000; Richardson, 2010; Richardson and Butler, 2012; Duncan, Scot and Baum, 2013).

Such negatve images may provide reasons why so many employees do not identfy the tourism and hospitality industries as a ‘career choice’ but rather as a ‘stop gap’ whilst looking for ‘something beter’ (Richardson, 2009; Duncan et al., 2013).

Hypotheses and research method

Tacit knowledge is argued to be critcal to a frm’s capacity to generate and sustain compettve advantage, but a partcularly important issue for tourism organisatons is how to atract people possessing this tacit knowledge. Many studies have found that students did not believe an employment in the sector would offer them the factors they found important in their job choice. In consequence, they do not plan to purse a job in tourism upon graduaton or consider tourism jobs as the frst stepping stone to a career elsewhere and leave the industry within a few years (King, McKercher, and Waryszak, 2003; Lu and Adler, 2009; Jiang and Tribe, 2009; Richardson, 2010; Richardson and Butler, 2012). Leaving the industry is connected with knowledge outlow, which is partcularly acute due to the loss of valuable tacit knowledge which cannot be easily and quickly recovered. As a result, the tacit knowledge acquired during studies and frst years of work is leaking out of the tourism sector. The consequences of this leakage include loss of the training costs and the tme spent on coaching these workers. Moreover, the staff turnover hampers the possibilites for development of knowledge because staffs who already have other plans for their working life than a career in tourism are unlikely to have adequate motvaton to contribute to development processes in the frm (Hjalager, 2002).

One of the factors that affects the propensity to work in tourism is previous work experience. Many studies recognize the relevance of previous experiences to the decision to take up and to contnue career in the tourism industry. Most of them indicate that the negatve image of the industry held by hospitality and tourism students appears to be developed with the increase in the exposure to working life in the industry through a part-tme employment and student placements (Kusluvan and Kusluvan, 2000; Jiang and Tribe, 2009; Richardson, 2010). According to Barron and Maxwell the more exposure students have to the hospitality industry, the less commitment they demonstrate (1993).

It is also interestng to determine the relatonship between percepton of tourism studies and a propensity to work in the tourism industry. Birdir (2002, afer: Roney and Ӧztn, 2007) surveyed tourism students in Turkey in order to fnd out the reasons why some students were not eager to work in the industry afer graduaton. The main reason they stated was the lack of quality educaton in tourism to enable them to be successful in the sector.

The aim of this research is to investgate students’ attudes towards career in the tourism industry and its determinants in the knowledge management context. Specifcally, this research tries to ascertain to what extend perceived atractveness of tourism employment, previous experiences and study satsfacton can influence the propensity to treat the hospitality and tourism industry as a long-term career sector. On the basis of literature review the following hypotheses are developed.

- H1: Low atractveness of tourism employment perceived by students deteriorates the willingness to undertake a long-term career in tourism.

- H2: Work experience in the tourism industry deteriorates the willingness to undertake a long-term career in tourism.

- H3: The negatve experience with the studies deteriorates the willingness to undertake a long-term career in tourism.

The target populaton of the present study comprised undergraduates and graduates enrolled in tourism and hospitality studies in universites in Poznan. Eight public and private higher educaton insttutons offered bachelor and master degrees in tourism in 2012 and a total of 4150 students took tourism and hospitality courses. To obtain a representatve subset of the target populaton a single-stage cluster sampling was employed. The sample size was determined based on statstcal precision approach – assuming the confdence level at 95%, the desired precision at 5%, and the degree of variability at 50%, and applying the fnite populaton correcton produced the minimum sample of 352 respondents.

A measurement instrument was developed based on a review of the literature and previous studies on attudes of students towards a career in the tourism industry, namely Kusluvan and Kusluvan (2000), Blomme, van Rheede and Tromp, (2009), Bednarska and Olszewski (2010), Richardson and Butler (2012). The questonnaire consisted of four main components. Partcipants were requested frst to envisage an ideal employer and rate a range of 16 items displaying various dimensions of working conditons based on their expectatons. In the second secton they were asked to assess the analysed atributes regarding employers in the tourism industry. The data enabled to compute the gaps between preferred and perceived job/organisaton atributes***. Secton three sought informaton about respondents’ willingness to pursue careers in the tourism industry. In the last secton students reported their age, gender, year of study, study mode, study degree, attude to tourism studies, and work experience. The inquiry form contained closed-ended questons, for gradatons of opinions a sevenpoint Likert scale was used, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to ”strongly agree” (7).

Data was collected through group-administered questonnaires distributed during a regularly scheduled class period. A total of 353 partcipants were recruited for the study. Due to incomplete or incoherent informaton 8 questonnaires were excluded, which resulted in 345 usable questonnaires for further analysis. The sample was demographically diverse. Partcipants ranged in age from 18 to 38 years old, with the mean age of 22; and 71 % of them were female. The majority of undergraduates and graduates were at public university (75 %), pursuing bachelor degree (59 %), and the sample was dominated by full tme students (73 %). 73 % of those surveyed declared tourism studies to be their frst choice and 47 % of them had work experience in the tourism industry. Table 1 shows descriptve statstcs for the sample.

| Variable | Category | Share [%] |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 71.2 |

| Male | 28.8 | |

| Age | 20 and less | 22.1 |

| 21-22 | 35.7 | |

| 23-24 | 34.9 | |

| 25 and more | 7.3 | |

| First choice studies | Yes | 72.8 |

| No | 27.2 | |

| Work experience in tourism | Yes | 47.1 |

| No | 52.9 | |

| Study degree | Bachelor | 58.8 |

| Master | 41.2 | |

| Study mode | Full time | 72.8 |

| Part time | 27.2 | |

| Year of study | First | 18.9 |

| Second | 8.4 | |

| Third | 25.3 | |

| Fourth | 18.3 | |

| Fifh | 29.1 | |

| Type of school | Public | 75.1 |

| Non-public | 24.9 |

The data analysis involved descriptve statstcs and correlatons to portray the main features of variables under study and relatons between them. In order to confrm the dimensionality of the questonnaire the factor analysis was performed. Chi-square and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were employed to assess signifcant differences among groups. The statstcal processing of the survey data was conducted using the SPSS sofware package.

Analysis

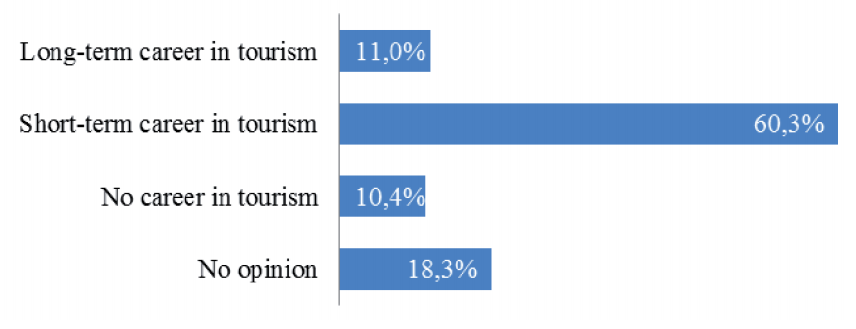

To begin with, the results of dependent variable, i.e. at tude towards career in tourism, will be presented. As Figure 1 shows, over 60% of respondents treat tourism jobs are short-lived professions, with more than 10% intending not to start a career in the tourism industry at all. Only 11% of students plan long-term career in tourism.

Then, the influence of at ract veness of tourism employment on at tude towards career in tourism was examined. An exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotat on was performed to reduce the number of variables. All 16 items loaded resulted in a four-factor structure, account ng for 67.7 % of the total variance. Factors were labelled as economic benef ts and development, social relat ons, job content and work-life f t, and customer relat ons. The results of the procedure are presented in Table 2.

| Variable | Number of items | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Economic benef ts & development | 6 | 0.870 |

| 2. Social relat ons | 5 | 0.852 |

| 3. Job content & work-life f t | 4 | 0.704 |

| 4. Customer relat ons | 1 | - |

Basic stat st cs for the study variables are reported in Table 3. It presents means, standard deviat ons, and correlat ons among the computed gaps between preferred and perceived job/organisat on at ributes for generated constructs. The picture that emerges from the table is that students generally do not believe that a career in the tourism industry will off er them values they f nd desirable, economic benef ts and development opportunit es being the worst perceived dimension.

| Variable | Mean | Standard deviation | Correlation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | |||

| 1. Economic benefits & development – gap | 0.7891 | 0.9324 | 1.00 | |||

| 2. Social relat ons – gap | 0.7513 | 0.9364 | 0.70** | 1.00 | ||

| 3. Job content & work-life fit – gap | 0.7683 | 0.9890 | 0.56** | 0.52** | 1.00 | |

| 4. Customer relat ons – gap | 0.6429 | 1.4392 | 0.16* | 0.17** | 0.17** | 1.00 |

| * Signif cant at the 0.05 level, ** signif cant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | ||||||

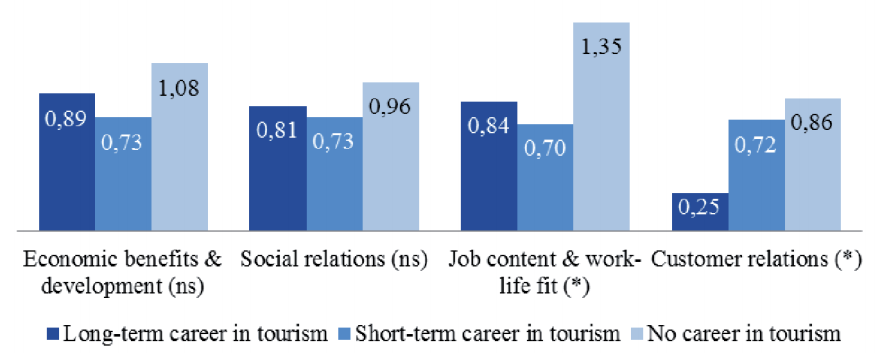

It can be assumed that the negat ve image of the industry as an employer has a negat ve impact on plans for a career in tourism. In order to ident fy relat ons between tourism employment percept ons and intent ons of students to pursue tourism careers, the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied. The results of the analysis are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Attitudes towards career and percept on of tourism employment

With respect to hypothesis 1, mixed evidence has been found. Signif cant diff erences in the percept on of work concern two groups of variables: customer relat ons and job content & work-life f t. Students planning longterm career in tourism evaluate customer relat ons signif cantly bet er than their colleagues not planning a career and those who treat work in tourism as transitory. Job content and work-life balance is also signif cantly bet er assessed by those who plan career in tourism than those who do not.

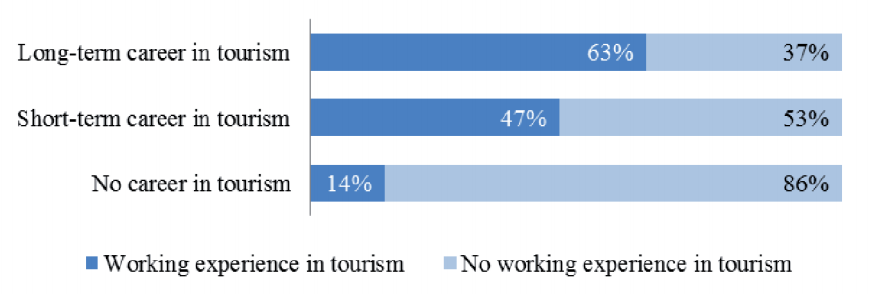

The hypothesized negat ve eff ects of working experience on intent ons to apply for a job in tourism have not found support in the data. Figure 3 shows that students who have been exposed to working life in tourism are signif cantly more commit ed to long-term career in the industry.

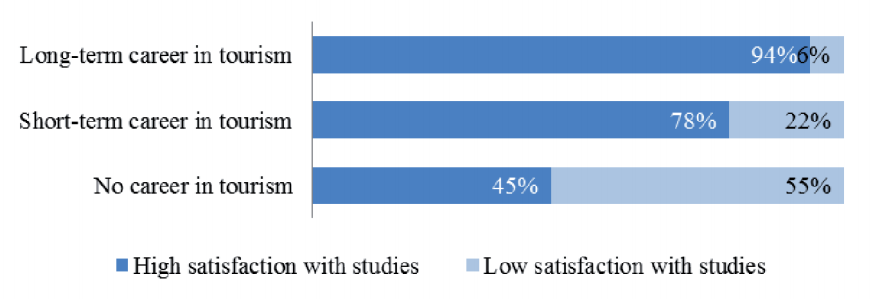

The third hypothesis was posit vely verif ed. Students who are sat sf ed with their studies are signif cantly more willing to undertake long-term career in tourism. As displayed in Figure 4, majority of students who plan career in tourism declare that they are sat sf ed with higher education.

Summarizing, as hypothesized, unfavourable image of tourism employment and dissat sfact on with studies have a negat ve impact on commitment to tourism careers. Unexpectedly, students with working experience in tourism are more interested in pursuing tourism-related jobs, thus the second hypothesis cannot be confirmed.

Discussion

The research has invest gated the impact of percept on of tourism employment on students’ at tude to work in tourism. The results of the study conf rm previous f ndings indicat ng transitory nature of career in tourism (Jiang and Tribe, 2009; Kusluvan and Kusluvan, 2000; Richardson, 2010; Richardson and Butler, 2012; Duncan et al., 2013). However, the problem of limited loyalty towards employer concerns not only students of tourism and hospitality but is typical for entering the labour market representat ves of generat on Y. According to Solnet’s research, the younger the employees, the more likely they are to quit unexpectedly (2011).

The f ndings of the study correspond also with those obtained in the course previous research, which highlighted that the negat ve image of the industry held by hospitality and tourism students caused them not to plan to pursue a job in tourism upon graduat on or to leave the industry within a few years (King et al., 2003; Lu and Adler, 2009; Richardson, 2010; Maxwell, Ogden and Broadbridge, 2012). Another noteworthy result is that with the increase in the exposure to working life in the industry, students tend to be more commit ed to tourism careers. This is not in line with Roney and Ozt n (2007), Koyuncu, Burke, Fiksenbaum and Demirer (2008), and Jiang and Tribe (2009), whose research revealed that work experience in the tourism industry led to deteriorated percept on of working condit ons and more pessimist c view on future job prospects in tourism. The present invest gat on also echoes previous observat on that respondents’ at tude to tourism studies is posit vely related to future employment opportunit es percept ons (Roney and Ozt n 2007).

Several pract cal implicat ons of the invest gat on can be pointed out. First of all, tourism companies, striving for retent on of the tacit knowledge, need to ident fy the expectat ons of employees and modify their working condit ons to ensure they are receiving posit ve experiences while working. Bearing in mind that students represent generat on Y, the employers should respond to their specif c expectat ons. In accordance with numerous studies, they are looking to make a contribut on to something worthwhile, to have their input recognized from the start, and they are used to fast outcomes and would not consider devot ng years to developing their career. Moreover, they dislike menial and repet t ve work and seek new challenges regularly (Cairncross and Buultjens, 2007; Solnet and Hood, 2008). The ability to create working environment that will induce employees’ loyalty is a challenge for all employers of generat on Y workers. Employers should keep in mind that the most sought af er organizat onal at ributes by generat on Y graduates include heavy investment in training and development of employees, care about employees as individuals, variety in daily work, freedom to work on one’s own initatve and scope for creatvity in one’s work (Solnet and Hood, 2008).

Of partcular interest are the results concerning the impact of past work experiences on intenton of taking up a long-term career in the tourism industry. Having them in mind tourism companies need to intensify their training programs to ensure students are receiving positve experiences while working during their degree. Moreover, they should modify their student placements offer, to put it in line with prospectve employers expectatons. Solnet’s research highlights the importance of making a good frst impression on new employees, partcularly when they are in their frst job (2011).

The results clearly indicate that students’ satsfacton with the study fosters their decision to prolong their engagement in the tourism industry as an employee. Making study programs more atractve will therefore lead to the higher satsfacton with the study, and as a result reduce the knowledge leakage outside tourism sector. Universites should also increase students’ practcal training in order to give them more tme to experience tourism jobs. On the other hand students should be made aware of working conditons in the tourism industry before they are enrolled. In order to reduce the gap between percepton and expectatons “students need to be informed about employment opportunites so that their career decisions are based on choice rather than chance” (Hing and Lomo, 1997, afer: Kusluvan and Kusluvan, 2003, p. 96).

Undoubtedly, a limitaton of this study is that it was carried out only at universites in one city in Poland. Although students are appropriate respondents for the study, due to unique characteristcs of the populaton the results may not relate to a sample of other prospectve employees who have more working experience and are at other stages of their careers. The nature of the sample limits generalizability of the results. Therefore, generalizatons beyond the specifc context of this research must be guarded. Thus, replicaton using a more diverse sample would be benefcial. Stll to be examined is the degree to which the results could be confrmed for other target groups. Further studies are needed to verify or repudiate these fndings within different contexts.

Conclusion

Growing recogniton of the signifcance of tacit knowledge in gaining a compettve advantage has resulted in an intensifed awareness amongst practtoners and researchers to beter appreciate how to atract and retain employees who are “owners” of tacit knowledge. Taking this into account, contnuous study of changing expectatons of workers entering the labour market seems necessary, partcularly as generaton Y represents distnct expectatons from other groups. By investgatng their employment expectatons, companies would beneft from obtaining guidelines for the tacit knowledge management. This is due to the fact that the acquisiton and retenton of knowledge embedded in human minds requires atractve employment conditons which are in line with employee requests.

Tacit knowledge leakage can lead to adverse consequences for the employer, the employee and the educaton system, as:

- The theoretcal knowledge (embrained knowledge), acquired during studies will not be completed and translated into practcal knowledge (embodied knowledge);

- Investments made on the newly adopted employee are lost; knowledge and tme spent on employee inducton to the company are wasted;

- Graduates at the beginning of their career ofen change their career path, which is associated with inefcient educatonal resources allocaton.

Practcal implicatons for knowledge management concern: employees selecton process, methods of knowledge protecton, and methods of minimizing the costs of the loss of tacit knowledge. During the recruitment process, companies should select employees who are likely to treat tourism jobs as long lived professions, i.e. those who already have working experience in tourism, as well as those who are satsfed with their studies. Companies should strive to minimize the costs of knowledge loss by codifcaton process and ongoing internal learning. Tacit knowledge can be preserved, in part, when frms promote employee interacton, collaboraton, and diffusion of non-redundant tacit knowledge (Droege and Hoobler, 2003). Thus, tacit knowledge will contribute to gaining the compettve edge regardless temporary human capital outlow.

References

- Almeida, P., Kogut, B. (1999). The localizaton of knowledge and the mobility of engineers in regional networks. Management Science, 45(7), 905-917.

- Ambrosini, V., Bowman, C. (2008). Surfacing tacit sources of success. Internatonal Small Business Journal, 26(4), 403-431.

- Argot, L., Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge transfer: A basis for compettve advantage in frms. Organizatonal Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 150-169.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained compettve advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Barron, P.E., Maxwell, G.A. (1993). Hospitality management students’ image of the hospitality industry. Internatonal Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 5(5), 5-8.

- Barron, P.E., Maxwell, G.A., Broadbridge, A., Ogden, S. (2007). Careers in hospitality management: Generaton Y’s experiences and perceptons. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 14(2), 119-128.

- Baumard, P. (1999). Tacit knowledge in organizatons. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publicatons Ltd.

- Bednarska, M., Olszewski, M. (2010). Postrzeganie przedsiębiorstwa turystycznego jako pracodawcy w świetle badań empirycznych. In: S. Tanaś (Ed.), Nauka i dydaktyka w turystce i rekreacji (pp. 277-286). Łódź: Łódzkie Towarzystwo Naukowe.

- Blackler, F. (1995). Knowledge, knowledge work, and organizatons: An overview and interpretaton. Organizaton Studies, 16(6), 1021-1045.

- Blomme, R., van Rheede, A., Tromp, D. (2009). The hospitality industry: An atractve employer? An exploraton of students’ and industry workers’ perceptons of hospitality as a career feld. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Educaton, 21(2), 6-14.

- Cairncross, G., Buultjens, J. (2007). Generaton Y and work in the tourism and hospitality industry: Problem? What problem? Centre for Enterprise Development and Research Occasional Paper, 9, 1-21.

- Cooper, C. (2006)., Knowledge management and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(1), 47-64.

- da Silva, M.A.P.M (2012). The knowledge multplier. FEP Working Papers, 456, 1-27.

- Davenport, T.H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge: How organizatons manage what they know. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Dickerson, J.P. (2009). The realistc preview may not yield career satsfacton. Internatonal Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(2), 297-299.

- Droege, S.B., Hoobler, J.M. (2003). Employee turnover and tacit knowledge diffusion: A network perspectve. Journal of Managerial Issues, 15(1), 50-64.

- Duncan, T., Scot, D.G., Baum, T. (2013). The mobilites of hospitality work: An exploraton of issues and debates. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 1-19.

- Filatotchev, I., Liu, X., Lu, J., Wright, M. (2011). Knowledge spillovers through human mobility across natonal borders: Evidence from Zhongguancun Science Park in China. Research Policy, 40(3), 453-462.

- Gallupe, B. (2001). Knowledge management systems: surveying the landscape. Internatonal Journal of Management Reviews, 3(1), 61-77.

- Granoveter, M. (1985). Economic acton and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481-510.

- Hallin, C.A., Marnburg, E. (2008). Knowledge management in the hospitality industry: A review of empirical research. Tourism Management, 29(2), 366-381.

- Hjalager, A-M. (2002). Repairing innovaton defectveness in tourism. Tourism Management, 23(5), 465-474.

- Hjalager, A-M. (2003). Global tourism careers? Opportunites and dilemmas facing higher educaton in tourism. The Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport and Tourism, 2(2), 26-38.

- Jiang, B., Tribe, J. (2009). ‘Tourism jobs – short lived professions’: Student attudes towards tourism careers in China. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Educaton, 8(1), 4-19.

- Kaj, U., Pekka, P., Hannu, V. (2003). Tacit knowledge acquisiton and sharing in a project work context Internatonal. Journal of Project Management, 21(4), 281-290.

- King, B., McKercher, B., Waryszak, R. (2003). A comparatve study of hospitality and tourism graduates in Australia and Hong Kong. Internatonal Journal of Tourism Research, 5(6), 409-420.

- Kogut, B., Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the frm, combinatve capabilites, and the replicaton of technology. Organizaton Science, 3(3), 383-397.

- Koyuncu, M., Burke, R.J., Fiksenbaum, L., Demirer, H. (2008). Predictors of commitment to careers in the tourism industry. Anatolia: An Internatonal Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 19(2), 225-236.

- Kusluvan, S., Kusluvan, Z. (2000) Perceptons and attudes of undergraduate tourism students towards working in the tourism industry in Turkey. Tourism Management, 21(3), 251-269.

- Leonard, D., Sensiper, S. (1998). The role of tacit knowledge in group innovaton. California Management Review, 40(3), 112-132.

- Lu, T., & Adler, H. (2009). Career goals and expectatons of hospitality and tourism students in China. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 9(1-2), 63-80.

- Maxwell, G.A., Ogden, S.M., Broadbridge, A. (2012). Generaton Y’s career expectatons and aspiratons: Engagement in the hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 17(1), 53-61.

- Nonaka, I. (1991). The knowledge-creatng company. Harvard Business Review, 69, 96-104.

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizatonal knowledge creaton. Organizaton Science, 5(1), 14-37.

- Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., Nagata, A. (2000). A frm as a knowledge-creatng entty: A new perspectve on the theory of the frm. Industrial and Corporate Change, 9(1), 1-20.

- Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension. London: Routledge. (University of Chicago Press. 2009 reprint).

- Richardson, S. (2009). Undergraduates’ perceptons of tourism and hospitality as a career choice. Internatonal Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(3), 382-388.

- Richardson, S. (2010). Generaton Y’s perceptons and attudes towards a career in tourism and hospitality. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 9(2), 179-199.

- Richardson, S., Butler, G. (2012). Attudes of Malaysian tourism and hospitality students’ towards a career in the industry. Asia Pacifc Journal of Tourism Research, 17(3), 262-276.

- Roney, S.A., Ӧztn, P. (2007). Career perceptons of undergraduate tourism students: A case study in Turkey. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Educaton, 6(1), 4-17.

- Solnet, D. (2011). Generaton Y as hospitality industry employees: An examinaton of work attude differences. Queensland: The Hospitality Training Associaton and University of Queensland.

- Solnet, D., Hood, A. (2008). Generaton Y as hospitality employees: Framing a research agenda. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 15(1), 59-68.

- Song, J., Almeida, P., Wu, G. (2003). Learning by hiring: When is mobility more likely to facilitate inter-frm knowledge transfer? Management Science, 49(4), 351-365.

- Szivas, E., Riley, M., Airey, D. (2003). Labor mobility into tourism. Atracton and satsfacton. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(1), 64-76.

- Tsoukas, H. (2003). Do we really understand tacit knowledge? In: M. EasterbySmith, M.A. Lyles (Eds.), The Blackwell handbook of organizatonal learning and knowledge management (pp. 411-427). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Zack, M.H. (1999). Managing codifed knowledge. Sloan Management Review, 40(4), 45-58.

- Zucker, L.G., Darby, M.R., Armstrong, J. (1998). Geographically localized knowledge: spillovers or markets? Economic Inquiry, 36(1), 65-86.