Received 27 February 2022; Revised 27 May 2022; Accepted 8 June 2022.

This is an open access paper under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Lefteris Topaloglou, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Economic School, Department of Regional Development and Cross-Border Studies, University of Western Macedonia, Kila, 50100 Kozani, HELLAS, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Lefteris Ioannidis, Post Graduate Student in Business Administration – MBA in Management Information Systems of University of Western Macedonia, Kila, 50100 Kozani, HELLAS, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

PURPOSE: This paper examines to what extent the governance modes of transition in the region of Western Macedonia (Greece) are effective and just, and whether they embed transition management, spatial justice, and place-based elements. To this end, the hypothesis tested in this paper is that spatial justice and place-based policy can make a positive contribution to just and well-managed transition. In this framework, the question examined is not about ‘who is in charge for designing and implementing transition policies?’ but about ‘what is the balance and mix of transition policies at the central, regional, and local levels of administration?’. METHODOLOGY: The article critically discussed the concept of transition as a fundamental societal change through the lens of efficiency and justice. Thus, the notions of transition management and spatial justice are thoroughly explored. It also embeds the concept of ‘place’ in this discussion. Therefore, the challenges, opportunities, and shortcomings of the place-based approach in the course of transition are examined. The empirical section contains a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods, such as the use of questionnaires and focus group meetings, preceded by background research, comprising mainly desk research. The above different cases of empirical work are not entirely irrelevant to each other. The validity of the research findings is strengthened by using multiple sources of evidence and data triangulation. The analysis at the empirical research level focuses on Western Macedonia in Greece. This region has all the characteristics of a coal-dependent locality, under an urgent need to design and implement a post-lignite, just, transition strategy. FINDINGS: Given that transition implies a profound and long-lasting societal, economic, and environmental transformation, new and pioneering modes of governance are necessary to tackle such a multifaceted challenge. The discourse about place, policies, and governance, reveals the need for focusing on a balance and mix of inclusive and multi-scalar policies instead of defining governance structures and bodies in charge for implementing transition policies. The launched transition governance model in Greece considerably deviates from the EU policy context. In fact, substantial shortcomings in terms of legitimacy, inclusiveness, and public engagement and overall effectiveness have been recorded. The empirical evidence reveals a rather clear top-down model than a hybrid one. The findings show that the governance model employed in the case of Western Macedonia, neither embeds spatial justice nor incorporates a place-based approach. IMPLICATIONS: Viewing the long-term process of transition through the lens of governance and policymaking, this paper challenges the assertion that the traditional top-down governance model is the most effective and fair approach. In this setting, the notions of transition management and spatial justice are thoroughly explored. The concept of ‘place’ is also embedded in this discussion. To this end, the challenges, opportunities and shortcomings of the place-based approach are analysed. Given that transition is by nature a multifaceted, multi-level and multi-actor process, an effective and just transition governance should reflect the views of different actors. In this sense, it seems that multi-level governance models for regions in transition need to harness existing interactions among different levels and actors. ORIGINALITY AND VALUE: After having touched upon the process of transition regarding the notions of ‘management’ and ‘justice,’ we embed the concepts of spatial justice and the place-based approach into governance transition practices. In this respect, the gap between efficiency and equity, redistributive logic (needs, results), and development policy (inclusive development) can be bridged through the so-called ‘spatial-territorial capital’ and spatially just, multi-level governance.

Keywords: just transition, place-based approach, spatial/social justice, governance, Green Deal, climate change

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, a frequent claim that has been made is that the traditional economic models need to be drastically reformed in order to address the challenges of the climate crisis, and the necessary transition to a green and sustainable economy, through technological innovations. Within this context, the concept of transition as fundamental changes within a given societal system has become a center of scientific and policy debates, interconnected with environmental, economic, social and government dimensions of sustainability (EEA, 2021; Loorbach, 2007). As a result, transition is seen as a means to tackle persistent problems related to transformative, and cross-cutting changes, encompassing major shifts in society’s goals, practices, norms, and governance approaches (Jansen, 2003; Meadowcroft, 2000; Scott & Gough, 2004). Likewise, Lund Declarations in 2009 and 2015, called upon Member States and European Institutions to focus research on the grand challenges of our times by moving beyond rigid thematic approaches and shifting the focus to society’s major needs.

The fact that persistent challenges are resistant to traditional policies, have raised the questions of systemic, integrated, and coherent policy responses which involve a just and efficient governance of the transition process (Loorbach, 2007; Petrakos, Topaloglou, Anagnostou, & Cupcea, 2021; Topaloglou, 2020, 2021). In particular, a research gap is identified in the interplay between environmental pressure, technological novelties, societal structure, administrative setting, and economic resilience of a given region, which defines, to a certain extent, the intensity of transformations (Kemp, Loorbach, & Rotmans, 2007; Loorbach, 2007; Rotmans, Kemp, & Asselt, 2001; Voss, Smith, & Grin, 2009). In this setting of multiple challenges and systemic changes in conjunction with the uncertain, co-evolutionary, and unpredictable nature of the transition, the policy interventions and governance configurations in open market economies, may generate winners and losers in space and society, thus challenging spatial and social justice (EEA, 2021; Madanipour, Shucksmith, Talbot, & Crawford, 2017).

Viewing the long-term process of transition through the lens of governance, it is uncontroversial to state that the traditional top-down model is currently challenged as the most effective and fair approach. Given that transition is by nature a multifaceted, multi-level and multi-actor process, an effective and just transition mechanism should reflect the views of different actors, emphasize the engagement of stakeholders, promote social dialogue as well as the active involvement of civil society, and be based on a solid communication strategy (EC, 2020a; Loorbach, 2007). Citing Börzel and Risse (2010), governance is considered as ‘the various institutionalized modes of social coordination to produce and implement collectively binding rules or to provide collective goods. From the functionalist point of view, multilevel governance describes the diffusion of authority away from the central state, in which coordination takes place at discrete levels across vast reaches of scale (Hooghe & Marks, 2001; Hooghe & Marks, 2020). In this sense, it seems that multi-level governance models for regions in transition need to harness existing interactions among different levels and actors, as well as acknowledge that boundaries between levels and competences can sometimes be ‘fuzzy’ (EC, 2020b). The compelling research question addressed in this work, relates to the mix of just transition policy making and governance configuration that is able to serve spatial and social justice as well as the implementation of a place-based governance framework.

This paper attempts to examine to what extent the governance modes of transition implemented so far in the case of the region of Western Macedonia in Greece, are effective and just and whether they embed transition management, spatial justice, and place-based elements. Based on Edward Soja’s work (2010), we conceptualize spatial justice as the fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and the opportunities to be used. In this framework, we critically discuss the concept of transition as a fundamental societal change through the lens of justice and efficiency. Thus, the notions of transition management and spatial justice are thoroughly explored. We also attempt to embed the concept of ‘place’ in this discussion as a socially constructed concept (Hassink, 2020), thus, the challenges, opportunities, and shortcomings of the place-based approach are examined. The empirical section involves a survey of the governance mechanism implemented in the case of Western Macedonia among experts on transition issues in Greece. The case of Western Macedonia has been selected, as the region has all the characteristics of a coal-dependent locality, under an urgent need to design and implement a post-lignite, just transition strategy within the EU Green Deal context.

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section provides a theoretical discussion and a synthesis of existing bodies of literature on transition, spatial justice, place-based approach, and governance. The following section outlines the transition governance frameworks in EU and Greece in relation to the European Green Deal and especially the Just Transition Fund Regulation. Then, we present the empirical elements and results of the fieldwork research, while the last section provides conclusions and policy recommendations for improving the efficacy and the fairness of the current governance mechanism.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The notion of transition is theorized as a process of fundamental change within the structure of a given societal system (Frantzeskaki & de Haan, 2009), in which ‘degradation’ and ‘breakdown’ co-exist for a certain period with ‘build up’ and ‘innovation’ (Gunderson & Holling, 2002). Historical evidence indicates that before the transition phase occurs, societal systems have experienced long periods of relative stability and optimization that are followed by relatively short periods of radical change. Within this context, governance of transformations of such a critical magnitude, emerges as a crucial issue. Existing literature provides ample insights into the dynamics of transitions in the endeavor of establishing an alternative paradigm (Kemp et al., 2007; Voss et al., 2009). However, the question of how the transition could be effectively and fairly governed remain ambiguous.

The transition management approach

Loorbach (2010) invokes the notion of transition management as a governance concept, based upon complex systems theory on the one hand and practical experimental approach on the other. In conceptual terms, this approach offers a framework that can simultaneously analyze and manage long-term changes and ongoing governance practices in society, economy, and the environment. From this pioneering point of view, the concept of transition management reflects a normative model by embedding the long-term objective of sustainability, while at the same time suggesting a prescriptive governance approach at the operational level. In fact, the transition management approach goes a step further in comparison to process management approaches, through focusing on sustainability narratives and lessons learned from experiments (Frantzeskaki, Loorbach, & Meadowcroft, 2012). Despite this promising perspective of transition management, in which theory and practice-oriented research co-exist and are fed to each other, this hybrid approach is still in early stages of development, and there is plenty of room for amplification (Rotmans et al., 2001; Voss, Bauknecht, & Kemp, 2006).

Current developments in the spheres of economy, technology, demography, and climate change have brought to the fore the society whose social structure is made up of networks (Castells 2009; Teisman 1992; Voss et al., 2006) and an increasing societal complexity (Loorbach, 2010). From the evolutionary perspective, system theories use the concepts of transition and transition management as a means to provide a useful analytical framework from the organizational point of view (Senge, 1990), governance and political sciences (Kemp et al., 2007; Rotmans et al., 2001). Within this context, government, business, academia, civil society organizations and individuals, create formal and informal networks in which each actor’s views may either diverge or converge. From the democratic legitimacy point of view, however, such types of lose and informal policymaking may lead to deficits in transparency, thus creating a policy vacuum that needs to be addressed (Loorbach, 2010). The strengthening of the local governance could potentially help bridge the democratic deficit, but it needs a sound coordination and collaboration with all other actors, as well as cross cutting procedures and forces (Madanipour et al., 2017). In other words, policymaking should introduce novel approaches to learning, interaction, integration, and experimentation at the level of society instead of policy alone (Loorbach, 2010).

Fairness and spatial (in)justice perspective

While the transition management approach focuses on a well-managed transition, the concept of just transition is mainly based on social and environmental considerations, seeking to ensure the substantial benefits of a green economy transition which contribute to the goals of decent work for all, social inclusion and the eradication of poverty (EC, 2020a). Based on the EU Governance of Transitions Toolkit issued by the European Commission in May 2020, just transition can be defined as a [Transition which captures the opportunities of the transition to sustainable, climate neutral systems, whilst minimising the social hardships and costs]. According to ILO’s vision, just transition is a bridge from where we are today to a future where all jobs are green and decent, poverty is eradicated, and communities are thriving and resilient. In this regard, the required massive development efforts to reach a zero-carbon economy will create millions of new jobs. ILO also emphasizes the need to secure the livelihoods of those who may be negatively affected by the green transition (ILO, 2015).

After having touched upon the process of transition in relation to the notions of ‘management’ and ‘justice,’ we will introduce in this critical theoretical review, the concepts of spatial justice and place-based approach. Given the discussions over the years around justice, equity and inequalities, several scholars became aware of the geographic aspects of injustices (Heynen, Aiello, Keegan, & Luke, 2018; Jones et al., 2019). Ample evidence indicates that spatial inequalities have been increasing over time, favoring the metropolitan centers to the detriment of the less advanced regions (Iammarino, Rodriquez, & Storper, 2019; Rodriguez-Pose, 2018). Likewise, several papers show that agglomeration economies, integration dynamics, geographic coordinates and the EU Cohesion Policy, represent the major drivers that shape the pattern of regional disparities in Europe (Psycharis, Tselios, & Pantazis, 2020; Rodriguez-Pose, 2018; Petrakos, Kallioras, & Anagnostou, 2011). Smith (1994) describes justice as an answer to the question “who gets what, where, when and how.” The normative concept of ‘spatial justice’ with its holistic approach, places emphasis on the spatial or geographical aspects of justice and injustice. From this point of view, the social and the spatial processes are correlated since social processes are spatially reflected while spatial processes influence the social processes. Hence, spatial justice is the spatial dimension of social justice (Soja, 2010). Seen in this respect, the distribution of resources is considered a key factor in identifying (in)justice, with social justice focusing more on the distribution between social groups and spatial justice, than on the geography of the distribution (Madanipour et al., 2017).

According to Morange and Quentin (2018), social and spatial justices are multifaceted and overlapping notions, with a strong normative character and a broad variety of understandings. Many efforts in the literature have been exploring the extent to which economic growth benefits and risks vary among social groups and are affected by the power settings (Florida & Mellander, 2016). Envisioning spatial justice from the perspective of social justice, it requires devising rules that equally allocate urban resources to all social actors (Friendly, 2013). It also endows the combination of community engagement, active participation, and consultation among all major stakeholders (Rawls, 1999), reflecting potentially various “modes of governance” (Hooghe & Marks, 2001) and configurations of power (Topaloglou, 2020). Spatial justice is a component of social justice providing all people with equal rights to access and/or use spatial resources to meet their basic needs (Miller, 1999). In this logic, social justice can contribute to reducing or preventing economic inequalities and deprivation of resources (Soja, 2009) which may give rise to political discontent and populism (Rodriguez-Pose, 2018). In that sense, spatial justice literature deals with spatial imbalances by drawing policies and governance settings that will allow for a better allocation and utilization of existing resources, aiming to meet both the equity and efficiency goals (Petrakos, Topaloglou, Anagnostou, & Cupcea, 2021). Thus, the concept of spatial justice is one of the most fascinating topics in the recent bibliography of spatial studies (Topaloglou, 2020).

Spatial justice brings together two important forms of justice, distributive and procedural. Distributive justice is focused on identifying the forms of exclusion and injustice, while procedural justice places emphasis on actions and institutional arrangements that can reduce spatial injustice (Madanipour, Cars, & Allen, 2003). Just procedures are necessary, but not sufficient for the fairness of the outcome, while attention to the outcome may hide the injustices of the process within a particular locale (Soja, 2010). As indicated by Loorbach (2007), an exclusive focus on the outcome of the process may resemble a Machiavellian approach. To conclude, in light of the procedural paradigm, what matters are just institutions and procedures that are necessary to have a just society (Madanipour, Shucksmith, & Brooks, 2021; Soja, 2010). Interestingly, this discussion highlights strong links between the theoretical debate on spatial justice and the concept of a just transition which feed each other towards a governance perspective.

According to Madanipour et al. (2021), spatial justice also has a clear temporal dimension reflecting social relations that are not static in the course of time. This echoes the concept of sustainability which requires justice within and across generations (Brundtland, 1987). At the same time, just transition has been linked in this discussion to the pressures of climate change and the goals for a green zero-emission economy. Hence, adaptation to global environmental requirements due to the climate crisis should be pursued by employing the place-based logic, which in turn, should take into account spatial justice and territorial cohesion (Madanipour et al., 2017). To this end, the concepts of social and spatial justice cannot be separated from environmental justice. This approach brings to the fore the need to seek place-based approaches that challenge the “one size fits all” and space-neutral logic (Topaloglou, 2021).

To conclude, our hypothesis is that spatial justice and place-based policy are essential components of a just and well-managed transition. Thus, an interesting question to be explored in terms of policymaking and governance, is whether the efficacy and justice of the transition can be associated with spatial justice and place-bound policy.

Transition governance and the place-based approach

It should be stressed that despite common elements, spatial justice and place-based approaches, do not stem from a common theoretical standpoint (Petrakos et al., 2021). Place-based strategies reflect the ‘endogenous development’ focusing on locally available resources, such as local knowledge, innovation and learning, local clustering of activities, global networking, in which local institutions play a critical role (Asheim, 1996; Pike, Rodriguez-Pose, & Tomaney, 2016). Since the 1990s, a tendency to weaken the dominance of the top-down model (exogenous-oriented) is identified. At the same time, a focus on promoting endogenous potential (Vázquez-Barquero, 2003) and ‘development from below’ (Stöhr, 1990) started to emerge.

Based on this background, the place-based approach has provided a challenge to re-think spatially ‘blind’ policies. In this regard, the gap between efficiency and equity, redistributive logic (needs, results), and development policy (inclusive development) can be bridged through the so-called ‘spatial-territorial capital’ (Barca, McCann, & Rodríguez-Pose, 2012; Barca, 2019; Sarmiento-Mirwaldt, 2015). According to Petrakos et al. (2021), top-down and bottom-up policies need to find a working balance between efficiency and the territorial perspective. In this framework, the real question should not be about ‘who is in charge of designing and implementing development policies?’, but about ‘what is the balance and mix of policies at the central, regional, and local levels of administration?’ (Petrakos et al., 2021)

The concept of ‘place’ in the place-based approach, is detected, defined, and interpreted, through a relational perspective. Seen in this respect, the ‘place’ is not encapsulated, but porous as part of broader relationships, which can be horizontal, vertical, or transversal, reflecting a multilevel governance model (Madanipour et al., 2021). From this perspective, the idea of the place-based approach is of particular importance in this discussion. The place-based approach advocated mainly by the Barca Report, is ‘a long-term strategy aimed at making full use of the potential of a place and reducing inequalities and social exclusion in specific places by providing integrated services thorough multilevel governance (Barca, 2009). This approach relies on local knowledge-based assets and includes utilizing place-specific endogenous territorial capital and fostering institutional reforms. In this framework, a place-based approach reflects the regional ecosystem, where market, social, institutional and governance settings are intertwined, generating critical scale and cumulative effects (Giuliani, 2007). It is also argued that, by placing emphasis on local assets and capacities, this type of strategy can stimulate economic development through smart specialization (McCann, 2015).

At the same time, many concerns and critique have been raised about the fairness and efficiency of the place-based approach. Several scholars pointed out that place-based at inter-local level is not always fair, since it focuses on social inclusion and balanced development within regions, rather than equity across regions (Madanipour et al., 2021). In addition, this shift towards place-based approaches undermines the redistributive top-down logic of policy interventions aimed to increase spatial justice (Weck, Madanipour, & Schmitt, 2021). It has also been claimed that place-based solutions are not sufficient to tackle global-wide problems, such as environmental degradation and climate change (Rees, 2015; 2017). Moreover, it has been argued that the territory-based approach focusing on policy at the local level, ignores the wider perspective of uneven development at the national and international levels, inter-regional flows, and globalization (Hadjimichalis, 2019).

In an attempt to amalgamate the above discussion into a governance perspective, it is worth noting first, an unambiguous shift over the last decades from the centralized government-based State toward new modes of governance that place emphasis on networks and multilevel governance (Pike et al., 2016). In the same vein, OECD (2020), in its recent policy report, stresses the need for further autonomy through transfer of authority and responsibility for public functions from central government towards decentralized policymaking structures, associated with fiscal and administrative arrangements (Petrakos et al., 2021). Hooghe and Marks (2001) accentuate that the well-established top-down governance model began to be questioned by market-based drivers and multilevel modes of governance stratified across subnational, national, and supranational levels of government.

In the context of a long-term structural change, such as the drastic societal transition occurring in coal regions, new governance practices and effective transitional management mechanisms are necessary in order to tackle multifaceted social, economic and environmental transformations (Loorbach, 2007). At the same time, however, it is true that the central State and the liberalized market continue to play a decisive role as major societal changes are impossible to be effectively governed without these key players (Jessop, 1997; Meadowcroft 2007; Pierre, 2000; Scharpf, 1999). In fact, this requires a new balance between the state, the market, and the society, in which alternative agendas and perspectives will be intertwined with formal and informal networks fueling regular policymaking processes with new solutions, ideas, and practices (Heritier, 1999). From the spatial justice point of view, the decision-making setting reflects the abovementioned balance either through the distribution of resources (distributive justice) or through the fairness and transparency of decision-making (procedural justice) (Davoudi & Brooks, 2014; Israel & Frenkel, 2018; Madanipour, et al., 2021).

Petrakos et al. (2021) argue that the endeavor of transition requires a multi-level governance environment that gives room for some local control over the decision-making process, the financial means, and interventions. In other words, a higher degree of regional autonomy is essential, aiming to enhance the scope of place-based actions and innovation elements in the transition strategy (Baier & Zenker, 2020). In the same vein, Ladner, Keuffer, and Baldersheim (2016) claim that local autonomy is a highly considered feature of good governance. In this outline, multi-level governance should also make use of local territorial assets, ensure wide participation and consensus of local stakeholders, transfer responsibility at lower levels, as well as invest on capacity building and local knowledge (Hooghe & Marks, 2020). Only then will local and regional actors be able to deliver results that match the scale and intensity of the problems confronted. Transitions imposed by the climate crisis threat should be governed through novel forms of government–society interactions across different levels, which take into account the complexity of the interrelated problems (Prins & Rayner, 2007; Rabe, 2007).

Remarkably, in two recent Toolkits for Transition Strategies (EC, 2020a) and Transition Governance (EC, 2020b), the European Commission highlights that the governance of the transition process must be set-up in a participatory manner in order to correspond to the problems identified. Thus, participatory processes not only help to improve the quality of strategies but also ensure ownership and strengthen the legitimacy of the transition. To this end, transitions require multiple stakeholders to participate in the effort. For coal regions however, this is particularly difficult since these areas often do not have clear administrative boundaries. The Green Tank, an established think tank on energy issues in Greece, in its recent report, caried out a critical assessment and recommendations for the improvement of the governance mechanism of the Just Transition in Greece, drawing on best governance practices from other lignite regions in Europe (The Green Tank, 2021). The report concludes with a series of recommendations for the construction of a just and effective governance mechanism, which among others includes transparency and open access platforms, co-creative consultations, active participation of local governments and civil society and decentralized policy-making structures.

The European framework for governing transition

The European Green Deal constitutes the overarching EU policy framework aiming to ensure a just transition towards climate neutrality by 2050. Given that transition is associated with drastic economic and social transformations, it is widely agreed that the component of governance plays a critical role in the outcome of this transition endeavor. Governance mechanisms, however, in terms of laws, official and unofficial norms, practices and power settings, largely vary in each country reflecting different institutional frameworks and political perspectives.

As far as the EU policy context regarding governance of transition regions is concerned, three major relevant policy documents may be identified. First, the Just Transition Fund Regulation (EC, 2021a), which includes a strong governance framework, focuses on the Territorial Just Transition Plans. Specifically, the Regulation requires that the Territorial Just Transition Plans should encompass well-structured governance, involving inclusive partnerships, monitoring and assessment mechanisms, and a clear description of the role of each entity engaged in governance mechanisms.

Second, the Common Provisions Regulation (EC, 2021b) sets the governance mechanism context for governing the Territorial Just Transition Plans. In fact, this document incorporates a multilevel mode of governance as a prerequisite for access in relative EU funds. In particular, each Member State must establish an inclusive partnership consisted at least of public authorities, economic and social partners, and relevant bodies representing civil society organizations. Remarkably, these partnerships shall consult at least once a year.

The third document concerns the Governance of Transitions Toolkit (EC, 2020b) which provides guidelines for the design of governance structures and stakeholders engagement processes for coal regions in transition. It addresses the design of governance models, the part of stakeholder engagement and partnership, the role of social dialogue, and the role of civil society. It also defines the concept of “good” governance, which is based on six core principles: transparency, participation, rule of law, equity and inclusiveness, efficiency, and accountability.

The toolkit also highlights the risks arising from insufficient stakeholder engagement, such as increased uncertainty, rejection of outcome, loss of confidence – also associated with the inefficient use of resources, as well as the development of resistance related to ethical issues, such as the lack of participation in decision-making. Furthermore, it puts forward three levels of increasing stakeholder engagement: information, consultation, and cooperation. Finally, the toolbox recommends the implementation of the following seven Golden Rules for open and inclusive planning of a just transition at the regional level, as a means to enable a rapid and socially just transition of coal-dependent regions: Open invitations, Inclusion, Equality, Access to information, Feedback, Disclosure, and Engagement and participation.

The Greek transition governance mechanism

In September 2019, the Greek Prime Minister pledged from the UN podium to phase out all coal-powered electricity production by 2028. This commitment is enshrined in the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) submitted by the Greek government to the European Commission in December of 2019. Three months after the announcement of the decision to phase out lignite, the first governance structure came to the fore, under the title Government Committee for Just Development Transition in the context of a Ministerial Council Act. The Committee comprised of representatives of competent Ministries, empowered to politically oversee the overall transformation in lignite regions and coordinate the utilization of the available funding resources. It is worth noting that there was the possibility of choosing other bodies, such as local authorities, public organizations, agencies, environmental NGOs, and even any other person considered capable to assist on a case-by-case basis (without the right to vote). Notably, the Committee does not have an expiration date implying that it will operate throughout the entire course of the transition.

In parallel with the Government Committee, a Steering Committee was established with the mandate of preparing and implementing a Just Development Transition Program and the corresponding Territorial Just Transition Plans required for accessing funds from the EU Just Transition Fund. The members of the Steering Committee are Secretary Generals of several ministries relative to transition, the Governors of the lignite regions, the CEO of the Public Power Corporation (PPC), and the Director of the Greek manpower employment organization (OAED). The appointed Chairman of the Steering Committee was a person of recognized status, whereas the Steering Committee operates within the context of the Regulations or the European Structural and Investment Funds and reports to the Government Committee. On top of all that, a Technical Secretariat was set up to provide technical support to the Steering Committee in the planning, drafting and monitoring of the implementation of the Just Development Transition Program and the Territorial Just Transition Plans. The Technical Secretariat is also authorized to provide scientific, technical, and legal support.

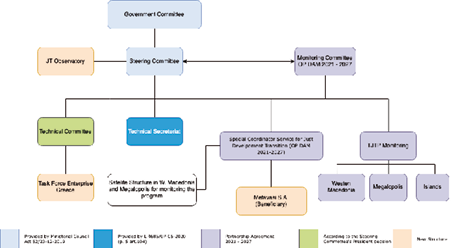

An initial formal reference to a governance mechanism for the lignite regions of Greece can be found in the Just Development Transition Plan, also known as the “Master Plan,” in August 2020. The Territorial Just Transition Plans that followed, in compliance with the rules of the Just Transition Fund Regulation, established a partnership of various categories of local partners, aiming to strengthen social dialogue and inclusive participation. The adopted governance setting, however, as illustrated in Figure 1 below, reflects a labyrinthine mechanism with several ambiguities in duties and roles of the eleven (11) different structures (Green Tank, 2021).

Figure 1. Organizational structure of the just development transition

in Greece

Source: Just Transition Development Plan (2020).

Apart from the managerial intricacy of the above governance mechanism, it is obvious that this governance mode is clearly applying a top-down approach. It is worth mentioning, for instance, that decision-making does not even include the mayors of the transition regions, ignoring their decisive role as advocates of the lignite areas’ transition issues. In addition, several key stakeholders, representatives of local communities, and NGOs are missing from the proposed structures, thus reflecting inadequate inclusiveness and representation (The Green Tank, 2021).

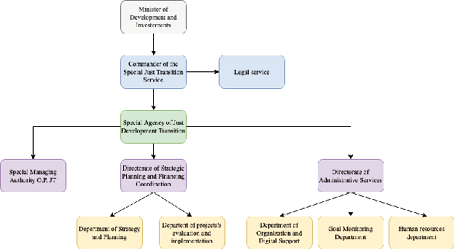

The main elements of the abovementioned centralized model of planning and governance of the transition was transposed into Law only very recently (4872/10-12-2021). According to the law, the Ministry of Development and Investment establishes a “Special Body for the Coordination of Just Development Transition” as an independent Unit, which reports directly to the Minister. This Special Body oversees the implementation of the Just Development Transition Program 2021-2027, the Territorial Just Transition Plans, as well as the utilization of all the available national and European funding sources. The Director of the Special Body is appointed by a joint decision of the Prime Minister and the competent Minister. In addition, the ‘Hellenic Company for a Just Development Transition’ (Metavasi S.A.) was also established, based in Athens, and governed by a five-member Board appointed by the decision of the Minister, with the main purpose of restoring and managing the assets of the Public Power Corporation in transition regions. The following diagram illustrates the clear top-down mode of transition governance in Greece as described in the Law.

Figure 2. The structure of the Special Body for Coordination of Just Transition

Source: Law 4872/10-12-2021.

The empirical research analysis focuses on the Western Macedonia region in Greece. Western Macedonia is the only land-locked region within the country, situated in the north-west and covering an area of 9.451 km2. Its population of 271,500 inhabitants constitutes around 2.6% of the national total. Western Macedonia’s economy is predominantly dependent on natural resource extraction. Since the mid-50s, the region has followed a coal-intensive development pathway, acting for several decades as the country’s energy pillar, due to its significant lignite reserves. As a result, a mono-industry economic structure has been created, mainly due to the economic reliance on lignite mining (160 thousand acres) and associated power plants (20% of the national net installed capacity). The coal-based economy contributes to more than 34% of the Gross Added Value of the Region, while more than 22.500 direct and indirect jobs are in the coal value-chain, indicating a significant multiplier effect in the local labor market (Petrakos et al., 2021). However, the lignite industry in Western Macedonia is in decline, drastically shrinking its share in the energy mix due to environmental (high emissions) and cost (emission tariffs) related considerations. Given this background, the government’s decision to phase out lignite completely by 2028, made the long-standing challenge of restructuring a very urgent one.

The empirical fieldwork employed a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods, such as the use of questionnaires and focus group meetings that were supported by background research, and comprised mainly desk research. Firstly, key documents at EU, national and regional levels have been assessed, referring to coal phase out policies, administrative settings, statistics, reports, studies, and relevant scientific articles. Specific focus has been given on the decision-making processes in the locality, by screening secondary data such as spatial planning and its articulation with development strategies at different levels of government. Aiming to obtain a holistic picture, exploratory field visits in the region of Western Macedonia have taken place, involving participative observations, informal talks, and discussions with local stakeholders. This approach aimed to explore narratives of stakeholders, and hidden interests and expectations of local elites (Yazan, 2015).

However, the most important sources of evidence were questionnaires involving experts with established status, academics, practitioners, executives at public local, regional, and national administrative level, and policy makers with in-depth knowledge on the transition framework in the region respectively. The fieldwork was conducted within the 2nd semester of 2021, both online and with physical presence. In this context, the questionnaire was sent to 48 individuals matching the aforementioned profile, out of which 41 responded, indicating an acceptable sample. That is so, considering the high level of expertise that post-coal transition requires along with the relatively small size of the population in Western Macedonia.

In addition to the above, a focus group meeting has been organized with local stakeholders, triggering responses that contribute to a greater understanding of the perceptions of participants (Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey, 2011). The above different instances of empirical work are not entirely irrelevant to each other. Using multiple sources of evidence, by applying data triangulation, increases confidence in the accuracy of the research findings.

The fundamental research question addressed, related to the extent to which the effective management of the transition at the level of governance, has the potential to acquire just and place-based characteristics. The questionnaire was divided into six sections involving: first, the six Core Principles of the EU Governance of transition toolkit, second, the seven Golden Rules for open and inclusive planning of a just transition at regional level, third, the risks arising from insufficient stakeholder engagement, fourth, the levels of stakeholder engagement, fifth, the dominant governance model in Western Macedonia, and sixth, the level of implementation of the place-based approach. Each respondent should answer closed-ended Likert-scale questions, ranging from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating ‘not agree at all’ and 5 ‘fully agree.’ The answer to each question was mandatory. To this end, in order for a result to be considered positive, it must exceed the value of 3.

As a preliminary analysis of the data, indicative descriptive statistic indexes (mean, standard error, standard deviation, confidence level (95%, etc.) were calculated for all the variables (questions), to provide some basic insights. The analysis revealed that the standard deviation for all questions is very low and the confidence level is very high.

Additionally, a correlation analysis (Pearson correlation coefficient or Pearson Product Moment Correlation – PPMC) between all variables highlighted the potential relationships between them. Thus, for each pair of variables/questions, the linear relationship between them (ranging from -1 to 1) were calculated. An absolute value of precisely 1 indicates that a linear equation describes the relationship between two variables perfectly, with all data points lying on a straight line. On the contrary, a value of 0 indicates that there is no linear dependency between the tested variables. To this end, correlation is an effect size. We can verbally describe the strength of the correlation using the scale that Evans (1996) suggests for the absolute value of r as follows: 0.00-0.19 ‘very weak,’ 0.20-0.39 ‘weak,’ 0.40-0.59 ‘moderate,’ 0.60-0.79 ‘strong,’ 0.80-1.00 ‘very strong.’ Typically, values above 0.5 are accepted as adequate correlations. The mathematical equation of PPMC is shown below:

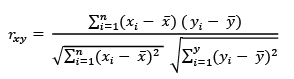

The first section of the empirical research addressed the concept of ‘good governance’ as defined by the six core principles of the EU Governance of Transition Toolkit (EC, 2020b). To this end, the level of implementing the principles of transparency, participation, rule of law, equity and inclusiveness, efficiency and accountability were examined. The empirical results, summarized in Table 1 and presented in Figure 3, reveal a low degree of satisfaction among the respondents, since all the obtained mean scores were below the value of 3, with the lowest scores recorded in the principles of participation and accountability. This evidence clearly indicates shortcomings in terms of legitimacy and effectiveness, which reflects a governance vacuum (Loorbach, 2010) and a lack of fairness in policy making (Madanipour, et al., 2021).

Table 1. Six Core Principles of the EU Governance of transition toolkit

|

|

Transparency |

Participation |

Rule of law |

Equity and inclusiveness |

Efficiency |

Accountability |

|

Mean |

2.76 |

2.20 |

2.68 |

2.39 |

2.44 |

2.24 |

|

Standard Error |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

|

Median |

3.0 |

2.0 |

3.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Standard Deviation |

1.0 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

|

Count |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

|

Largest(1) |

5.0 |

4.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

|

Smallest(1) |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Confidence Level (95.0%) |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

Figure 3. Six Core Principles of the EU Governance of transition toolkit

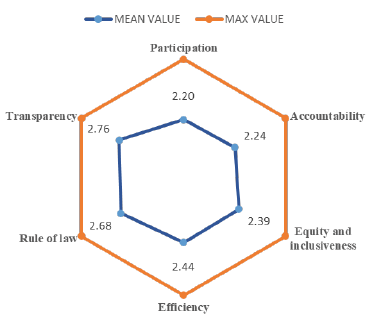

The next research section, explores the extent to which the seven golden rules for open and inclusive planning of a just transition (also included in the EU Governance of Transition Toolkit) are applied. These rules concern open invitations, inclusion, equality, access to information, feedback, disclosure, and engagement/participation. According to the results, summarized in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 4, the respondents consider that none of these golden rules are applied at a satisfactory level, signaling a low anticipation of the major challenges for active social participation and engagement. We also underline that the rules of accountability, feedback and inclusion have the lowest scores, reflecting to a certain extent procedural governance injustices (Madanipour et al., 2003) and reduced trust within the society (The Green Tank, 2021).

Table 2. Seven Golden Rules for open and inclusive planning of a just transition

|

|

Open invitations |

Inclusion |

Equality |

Access to information |

Feedback |

Disclosure |

Accountability |

|

Mean |

2.90 |

2.49 |

2.59 |

2.85 |

2.34 |

2.95 |

2.20 |

|

Standard Error |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Median |

3.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

3.0 |

2.0 |

3.0 |

2.0 |

|

Standard Deviation |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

|

Count |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

|

Largest(1) |

4.0 |

4.0 |

5.0 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

5.0 |

4.0 |

|

Smallest(1) |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Confidence Level (95.0%) |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

Figure 4. Seven Golden Rules for open and inclusive planning

of a just transition

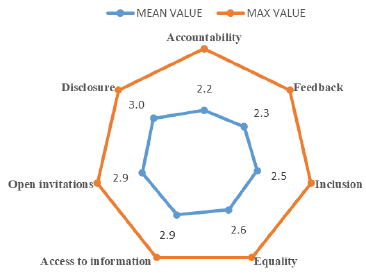

The risks arising from insufficient stakeholder engagement were addressed in the third set of questions, in order to assess the possible threats from the low involvement of key societal actors in the transition endeavor. In this respect, the risks addressed were increased uncertainty, rejection of outcome, loss of confidence, lack of participation in decision-making and resistance related to ethical issues. The findings demonstrated in Table 3 and Figure 5 show that the role of stakeholder engagement in avoiding serious risks in the course of transition is critical. It is worth noting that the highest values are found in the risks of increased uncertainty, lack of participation in decision-making and loss of confidence, suggesting the complexity, ambiguity, and uncertainty of such societal transformations occurring in lignite regions (Loorbach, 2010).

Table 3. Risks arising from insufficient stakeholder engagement

|

|

Increased uncertainty |

Rejection of outcome |

Loss of confidence |

Resistance related to ethical issues |

Lack of participation in decision-making |

|

Mean |

4.44 |

4.05 |

4.32 |

3.85 |

4.37 |

|

Standard Error |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Median |

5.0 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

5.0 |

|

Standard Deviation |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Count |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

|

Largest(1) |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

|

Smallest(1) |

2.0 |

3.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

3.0 |

|

Confidence Level(95.0%) |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

Figure 5. Risks arising from insufficient stakeholder engagement

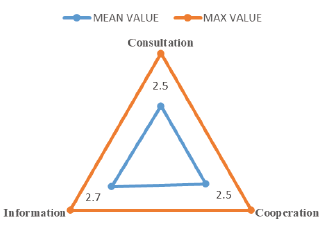

The fourth set of questions focused on assessing the level of participation in the partnerships during the process of planning and monitoring of the Just Transition Program for Western Macedonia. To this end, three levels of participation were assessed: information, consultation, and cooperation, to reflect a gradual escalation in the dynamics of partnerships. The results shown in Table 4 and Figure 6, clearly imply that there is low performance in all the levels of participation. This practically means that first, the one-way flow of information is not adequately ensured, second, the stakeholders cannot easily express their views and recommend policies (consultation), and third, joint decision-making forms (cooperation) are absent from the governance setting (Green Tank, 2021).

Table 4. Levels of increasing stakeholder engagement in the Partnerships

|

|

Information |

Consultation |

Involvement |

|

Mean |

2.72 |

2.49 |

2.49 |

|

Standard Error |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Median |

3.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Standard Deviation |

0.8 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Count |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

|

Largest(1) |

5.0 |

4.0 |

5.0 |

|

Smallest(1) |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Confidence Level(95.0%) |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

Figure 6. Levels of increasing stakeholder engagement in the Partnerships

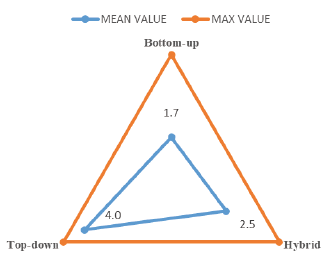

The fifth set of questions was aimed at evaluating the type of governance model applied in Western Macedonia. From this point of view, three categories of governance models were considered. First, the top-down model, where decision-making is carried out predominately by the central government. Second, the bottom-up approach in which decision-making and process implementation originates from lower levels and proceeds upwards. The third model is the hybrid one, which combines elements from the above mentioned two approaches. Based on results summarized in Table 5 and depicted in Figure 7, most of the respondents characterized the governance model implemented in the case of the region of Western Macedonia as a clear top-down governance mechanism. Interestingly, this occurs contrary to the general tendency to weaken the dominance of top-down model (Vázquez-Barquero, 2003) and the shift towards place-based approaches over the last decades (Weck et al., 2021).

Table 5. Transition Governance Model in Western Macedonia

|

|

Top-down |

Bottom-up |

Hybrid |

|

Mean |

4.02 |

1.71 |

2.54 |

|

Standard Error |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Median |

4.0 |

2.0 |

3.0 |

|

Standard Deviation |

1.0 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Count |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

|

Largest(1) |

5.0 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

|

Smallest(1) |

2.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Confidence Level(95.0%) |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

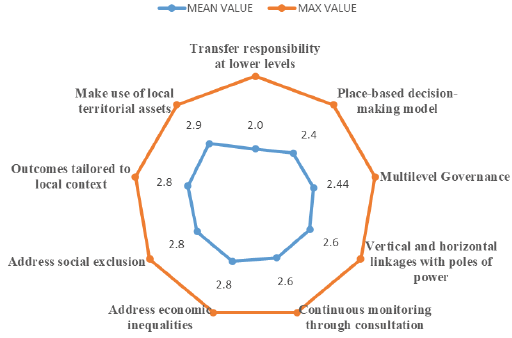

The last set of questions focused on testing the major components of the place-based hypothesis based on Barca’s definition (Barca, 2009). In this theoretical framework, the existing governance mechanism was rated according to the extent by which it: (a) makes use of local territorial assets, (b) will be able to address economic inequalities and social exclusion, (c) transfers responsibility to lower levels, (d) employs place-based decision-making and multilevel governance, (e) applies vertical and horizontal links with poles of power, (f) delivers outcomes tailored to the local context and (h) encourages continuous monitoring through consultation.

Figure 7. Transition Governance Model in Western Macedonia

Based on the results depicted in Table 6 and Figure 8, the majority of the respondents believe that the proposed transition governance mode, deviates substantially from the place-based approach. In particular, a considerable lack of decentralization was recorded in terms of transfer of responsibilities to the local level, which in turn is not able to activate the place-based decision-making logic. The findings also suggest that the proposed model for governing transition in Greece, favors neither multilevel governance, nor vertical or horizontal linkages among different power poles and places. As a result, this pattern promotes a purely centralized and vertical administrative setting that favors the core-periphery paradigm (Topaloglou, 2021). In addition, according to the prevailing perceptions, it seems that the governance model to be applied in the region is not able to address effectively economic inequalities and social exclusion. Furthermore, it does not take into consideration local peculiarities and local resources, nor does it generate outcomes adapted to the local context.

Table 6. Level of place-based approach

|

|

Make use of local territorial assets |

Address economic inequalities |

Address social exclusion |

Transfer responsibility at lower levels |

Place-based decision-making model |

Multilevel Governance |

Vertical and horizontal linkages with poles of power |

Outcomes tailored to local context |

Continuous monitoring through consultation |

|

Mean |

2.93 |

2.76 |

2.76 |

2.02 |

2.41 |

2.44 |

2.59 |

2.80 |

2.61 |

|

Standard Error |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Median |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Standard Deviation |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

|

Count |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

41.0 |

|

Largest(1) |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

4.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

|

Smallest(1) |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Confidence Level(95.0%) |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

Figure 8. Level of place-based approach

In the next section, we employed a Pearson correlation coefficient aiming to explore the strength and the direction (positive or negative) of the linear relationship between two variables. All involved variables in the research were examined and all pairs were tested. Figure 9 shows the Pearson values of the variable pairs that demonstrate either a positive or a negative statistically significant correlation, excluding the insignificant statistical correlations.

Table 7. Pearson correlations

|

|

Transparency |

Effectiveness |

Accountability |

Inclusion |

Access to information |

Involvement & participation |

Rejection of outcome |

Loss of confidence |

||||||||||

|

Inclusion |

0.6 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Access to information |

0.6 |

0.5 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Involvement & participation |

0.5 |

0.6 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Loss of confidence |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

|||||||||||||

|

Resistance related to ethical issues |

-0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

||||||||||||||

|

Lack of participation in decision-making |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

-0.6 |

|||||||||||||||

|

Cooperation |

0.5 |

-0.5 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Top-down |

0.5 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Bottom-up |

0.5 |

0.5 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Make use of local territorial assets |

0.5 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Multilevel Governance |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

-0.5 |

-0.6 |

|||||||||||||

|

Vertical and horizontal linkages |

0.5 |

0.5 |

||||||||||||||||

|

Continuous monitoring & consultation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.5 |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

The significant values depicted in Figure 7 allow us to make a number of interesting observations. First, the findings illustrated in the first column show ‘strong’ and positive correlations between ‘Transparency with inclusion’ (r=0.6). ‘Moderate’ and positive correlations are recorded between ‘Involvement & participation’ (r=0.5), ‘Bottom-up’ model (r=0.5) and ‘Vertical and horizontal linkages’ with poles of power. On the other hand, ‘moderate’ and negative relationships are recorded between ‘Transparency’ and ‘Loss of confidence’ (r=-0.5), ‘Resistance related to ethical issues’ (r=-0.5) and ‘Lack of participation in decision-making’ (r=-0.5), respectively. These findings highlight the critical role that transparency plays in designing inclusive transition policies that can ensure active involvement and participation of the key stakeholders. It is also evident that transparency seems to be connected to a bottom-up perspective and vertical and horizontal linkages in relation to power setting. On the other hand, lack of transparency seems to discourage active participation, reduces the feeling of confidence, and challenges the transition proposed policies.

The next ‘strong’ and positive relationships between ‘Effectiveness’ and ‘Access to information’ and ‘moderate’ relationship with ‘Cooperation’ implies that effective policy making requires open access processes and an in-depth level of participation. Furthermore, ‘Accountability’ shows a positive/strong relationship with ‘Involvement and participation’ and positive/moderate relationship with ‘Access to information,’ and ‘Multilevel Governance’. Respectively, negative/strong relationships are detected with ‘Lack of participation in decision-making,’ whilst negative/moderate relationships are recorded with ‘Loss of confidence’ and ‘Resistance related to ethical issues.’ This evidence suggests that accountability could be a key element in an engagement strategy of transition that incorporates multilevel governance modes and inclusive participation during the planning process.

Moreover, ‘Inclusion’ shows a positive/moderate relationship with ‘Multilevel Governance’ signifying the importance of interaction among distinct political levels and actors. To the contrary, negative/strong relationships are calculated with ‘Resistance related to ethical issues’ and ‘Lack of participation in decision-making’ and negative/moderate relationships with ‘Loss of confidence.’ It is inferred that inclusiveness of all the key categories of bodies, representing political makers, societal actors, economic agents, research institutions and distinct individuals, is a key precondition for obtaining the ‘ownership’ of the transition at the local level.

Next, ‘Access to information’ demonstrates a negative/moderate correlation with ‘Loss of confidence’ denoting the specific importance of the information diffusion within all parts and manifestations of the society, in the course of a trust building perspective. On the other hand, positive/moderate relationships are displaying with the variables of ‘Make use of local territorial assets’ and ‘Vertical and horizontal linkages.’ From the policymaking point of view, this finding makes a lot of sense if one considers that the more access to information, the better the use of endogenous resources and better implementation of a place-based policy will be.

Likewise, positive/moderate correlations are revealed between ‘Involvement and participation’ with ‘Bottom-up’ governance model and ‘Multilevel Governance.’ To the contrary, negative/strong relationships are displayed between ‘Involvement and participation with ‘Loss of confidence’ and negative/moderate relationships with ‘Top-down’ and ‘Resistance related to ethical issues.’ At a macroscopic view, it is obvious that a bottom-up approach and multilevel mode of governance are favored within an environment of active involvement and participation of the key actors. Conversely, low performances in participation are usually associated with top-down model of governance that may harm trust in transition policies and trigger ethic-driven resistances.

Interestingly, the risk of ‘Rejection of outcome’ seems to exhibit negative/moderate correlation with ‘Cooperation’ and ‘Multilevel Governance.’ In other words, the likelihood of rejecting the transition strategy is considerably decreased whether solid partnerships and multi-level governance are employed. Similarly, the ‘Loss of confidence’ shows a negative/strong relationship with ‘Multilevel Governance’ and positive/moderate relationship with ‘Continuous monitoring and consultation.’ This result, seems to be in line with the latter finding, indicating that a governance setting that encourages a broad involvement of actors on a multi-layered basis, in combination with permanent monitoring and essential consultation, strengthens trust building in relation to transition policies.

DISCUSSION

In this section, we attempt to cast some light upon the various aspects of just transition policy making and governance, by linking up the theoretical considerations with the documents’ analysis, and the empirical findings in Western Macedonia. The preceding analysis revealed that energy transition in coal regions concerns a fundamental change associated with major economic, societal, and environmental impacts. Given this background, our empirical findings suggest that the lower the local stakeholders’ participation in decision-making, the higher the ambiguity, uncertainty, and loss of local societies’ confidence towards central transition policies will be (Loorbach, 2010). On the other hand, however, our analysis showed that the notion of just transition is not irrelevant to the goals of sustainability and neutral climate considerations at a national and global level (Frantzeskaki et al., 2012; Rees, 2015; 2017). That is so since the question that arises is whether such a global-wide challenge can effectively be tackled solely as a territory-based approach. Many scholars touch upon this question, pointing out the decisive role of the central State in confronting the regional disparities (Hadjimichalis, 2019) and effectively governed major societal transformations (Jessop, 1997; Meadowcroft 2007; Pierre, 2000; Scharpf, 1999), questioning the adequacy of place-based logic.

The exploration of the transition’s governance model in Western Macedonia, revealed a clear top-down approach, rather than a bottom-up model or a hybrid one. It is worth pointing out that what is taking place in Western Macedonia does not reflect the prevailing governance approaches across the EU, where multilevel governance and place-based logics seem to dominate over the last years (Vázquez-Barquero, 2003; Weck et al., 2021). Concurrently, all modes of participation (information, consultation, cooperation) are evaluated as inadequate, whereas the factors of transparency, active involvement, participation, and inclusiveness, are clearly linked with bottom-up model, vertical and horizontal linkages, and multi-level governance. These findings constitute a major cause for alarm if one considers the fact of such deeply lignite-dependent economies, since the transition is a long-term and dynamic transformation that cannot be limited to the running programming period (2021-2027). To this end, decision-making and the implementation of resources should be placed in the geographic area where the transition activities are concentrating and, in order to have any realistic chance of success and obtain the true support of the local society, the governance model needs to become more inclusive.

Existing literature indicates a positive relationship between local autonomy and good governance, best use of local assets, and local knowledge (Ladner et al. 2016; Hooghe and Marks, 2020, Hooghe et al., 2020). Remarkably, the empirical evidence tends to confirm these assertions of literature, according to which ‘accountability,’ as a transfer of responsibility at a lower level, demontrates a positive correlation with the perspective of multilevel governance and active involvement of local stakeholders. At a macroscopic level, such types of multifaceted participatory processes could cover the democratic deficit, governance vacuum and democratic legitimacy in policy making in countries with centralized administrative structure, such as Greece. This makes a lot of sense in coal regions in particular, if one examines the critical role of societal actors and their engagement in the form of ‘ownership of the transition’ that could be implemented within a multi-layered governance setting.

Based on the assumption that a place-based approach contributes to spatial and social justice, we examined to what extent policymaking in Western Macedonia makes use of local territorial assets and addresses economic disparities and social exclusion in a way that deliver outcomes tailored to locality. The empirical findings clearly suggest that Western Macedonia lags significantly behind the place-based logic. Concurrently, this evidence brings to the fore the critical role of local capacities and leadership. It is uncontroversial to state that governing such a demanding and long-term plan requires a well-managed transition and visionary leadership. To this end, a high-level leadership group would be of utmost importance for decision-making processes and for clarifying roles and assignments across a variety of actors at the national, regional, and local levels.

CONCLUSION

In the previous analysis, a critical theoretical review of the literature on transition management, spatial justice and the place-based approach was attempted, aiming to amalgamate this discussion into a just, transition governance perspective in Western Macedonia in particular. Given that transition in the case of Western Macedonia implies a profound and long-lasting societal, economic, and environmental transformation, new and pioneering modes of governance are necessary to tackle such a multifaceted challenge. Viewed in this respect, competing notions, such as efficiency and equity, effectiveness and legitimacy, market and society, exogenous and endogenous drivers of development, intra-generational and inter-generational environmental justice, should be manifested and reflected to a certain extent in transition governance mechanisms.

Given the intricacy and multi-layered nature of the transition, we may safely argue that any governance approach cannot easily overcome these competitive challenges without taking them into account. Policymaking from this point of view requires new balances among mainstream, alternative, and sometimes antagonistic agendas. Also, it should take into account new types of informal and formal networks, and new approaches of public engagement and civil society’s involvement, that might reconcile the aforementioned tensions. To this end, a governance system, institutionally equipped to operate independently from political interventions and election cycles at national and local level, would contribute to the success of the transition. In this framework, the new discourse about place, policies, and governance, reveals the need for focusing on balancing and mixing inclusive and multi-scalar policies, instead of merely defining governance structures and bodies in charge of implementing transition policies, as applied in Western Macedonia.

Within the sphere of responsibility of the EU, three policy documents with strong governance framework have been discussed, that of the Just Transition Fund Regulation, the Common Provisions Regulation, and the Governance of Transition Toolkit. At the national level, the major transition governance-context initiatives and documents have been critically discussed as well. Based on insights gained from the empirical research, there is abundant evidence to claim that the launched transition governance model in Greece and Western Macedonia considerably deviates from the EU policy context. In fact, substantial shortcomings in terms of legitimacy, effectiveness, inclusiveness, and public engagement have been recorded, associated with a lack of trust among local stakeholders. The findings also imply that these weaknesses are fueling several risks, such as uncertainty, rejection of outcome, and lack of participation due to resistance related to ethical issues.

It seems that resilient, sustainable, and inclusive transformations in coal-dependent regions, such as Western Macedonia, require minimizing social distress, placing emphasis on competitive advantages locally and the fast-growing sectors globally, and responding to climate neutral challenges. To this end, the elements of effectiveness, justice and ‘place-bound’ in a transition’s governance, prove to be enabling factors to make transition pathway truly successful and tackling such multifaceted challenges and, sometimes, competing agendas. To sum up, a new operationalizing balanced perspective between the state, the market, and the society on the one hand, and the top-down and bottom-up policies on the other, seem to be crucial for a success and just governance transition pathway.

Finally, existing findings reveal that the governance model in Western Macedonia does not embed spatial justice, in terms of fairness and equitable distribution of power and socially valued resources in space, at a satisfactory level. To this end, the gap between efficiency and equity remains open, making it inadequate to design and implement an inclusive development policy. In addition, the proposed governance mechanism does not seem to incorporate a place-based approach in terms of harnessing the spatial territorial capital, local knowledge, multi-layered interactions among administrative structures, spatial levels, and actors. This policy framework does not favor either spatial-territorial capital, or just multi-level governance. Seen in this perspective, one could identify an interesting and promising interaction between the transition management, the spatial justice rationale, and the place-based approach in the governance of transition.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the comments and input provided by Dr. Nikos Mantzaris, Senior Policy Analyst of the Green Tank.

References

Asheim, B. (1996). Industrial districts as ‘learning regions: a condition for prosperity?” European Planning Studies, 4(4), 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654319608720354.

Baier, E., & Zenker, A. (2020). Regional autonomy and innovation policy. In M. Gonzalez-Lopez & B. T. Asheim (Eds.), Regions and Innovation Policies in Europe. Learning from the Margins (pp. 66-91). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Barca, F. (2009). An agenda for a reformed cohesion policy: A place-based approach to meeting European Union challenges and expectations. Independent Report prepared at the request of Danuta Hübner, Commissioner for Regional Policy, by Fabrizio Barca, Brussels. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/library-document/agenda-reformed-cohesion-policy-place-based-approach-meeting-european-union_en

Barca, F. (2019). Place-based policy and politics. Renewal: A Journal of Labour Politics, 27(1), 84-95. Retrieved from https://journals.lwbooks.co.uk/renewal/vol-27-issue-1/abstract-8980/

Barca, F., McCann, P., & Rodriguez-Pose, A. (2012). The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. Journal of Regional Science, 52(1), 134-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00756.x

Brundtland, G. (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. United Nations General Assembly document A/42/427. Retrieved from http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm

Börzel, T., & Risse, T, (2010), Governance without a state: Can it work? Regulation & Governance, 4(2), 113-134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2010.01076.x

Castells, M. (2009). The Rise of Network Society. West Sussex: UK: Wiley Blackwell, https://doi.org/10.1002/978144431951

Davoudi, S., & Brooks, E. (2014). When does unequal become unfair? Judging claims of environmental injustice. Environment and Planning A, 46(11), 2686–2702. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130346p

EC (2020a). Toolkit Transition strategies: How to design effective strategies for coal regions in transition. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/transition_strategies_toolkit_-_platform_for_coal_regions_in_transition.pdf

EC (2020b). Toolkit Governance of transition: Design of governance structures and stakeholder engagement processes for coal regions in transition. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/governance_of_transitions_toolkit_-_platform_for_coal_regions_in_transition.pdf

EEA. (2021). Building the foundations for fundamental change European Environmental Agency. Retrieved from https://www.eea.europa.eu/articles/building-the-foundations-for-fundamental-change

Evans, J. D. (1996). Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing.

Florida, R., & Mellander, C. (2016). The geography of inequality: Difference and determinants of wage and income inequality across US metros. Regional Studies 50(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.884275

Frantzeskaki, N., & De Haan, H. (2009). Transitions: Two steps from theory to policy. Futures, 41(9), 593–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2009.04.009

Frantzeskaki, N., Loorbach, D., & Meadowcroft, J. (2012). Governing societal transitions to sustainability. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 15(1/2), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSD.2012.044032

Friendly, A. (2013). The right to the city: Theory and practice in Brazil. Planning Theory and Practice, 14(2),158–179. http://doi.org/10.1080/1464935 7.2013.783098

Giuliani, E. (2007). The selective nature of knowledge networks in clusters: Evidence from the wine industry. Journal of Economic Geography 7(2), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl014

Gunderson, L.H., & Holling, C.S. (2002). Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Washington: Island Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.01.010

Hadjimichalis, C. (2019). “New” questions of peripherality in Europe or how neoliberal austerity contradicts socio-spatial cohesion. In T. Lang & F. Görmar (Eds.), Regional and Local Development in Times of Polarisation: Re-Thinking Spatial Politics in Europe (pp. 61-78). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1190-1_3

Hassink, R. (2020). Advancing place-based regional innovation policies. In M. Gonzales-Lopes & B. Asheim (Eds.), Regions and Innovation Policies in Europe (pp. 30-45). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789904161.00007

Hennink, M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2011). Qualitative Research Methods. London, UK: Sage. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2011.565689

Héritier, A. (1999). Policy-Making and Diversity in Europe: Escape from Deadlock. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Heynen, N., Aiello, D., Keegan, C., & Luke N. (2018). The enduring struggle for social justice and the city. Annals of the American Association Geography 118(2), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1419414

Hooghe, L., & Marks G. (2001). Multi-Level Governance and European Integration. Oxford, UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Hooghe, L, & Marks G. (2020). A postfuntionalist theory of multilevel governance. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22(4), 273-298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120935303

Iammarino, S., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2019). Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(2), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby021

ILO, (2015). World Employment Social Outlook: Trends 2015. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Israel, E., & Frenkel, A. (2018). Social justice and spatial inequality: Toward a conceptual framework. Progress Human Geography, 42(5), 647–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517702969

Jansen, L. (2003). The challenge of sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 11(3), 231–245. https://10.1016/S0959-6526(02)00073-2

Jessop, B. (1997). The governance of complexity and the complexity of governance: Preliminary remarks on some problems and limits of economic guidance. In A. Amin & J. Hausner (Eds), Cheltenham Beyond Market and Hierarchy. Interactive Governance and Social Complexity. Cambridge, UK: Edward Elgar. https://10.1007/978-3-663-11005-7_2

Jones, R., Moisio, S., Weckroth, M., Woods, M., Luukkonen, J., Meyer, F., & Miggelbrink, J. (2019). Re-conceptualising territorial cohesion through the prism of spatial justice: Critical perspectives on academic and policy discourses. In T. Lang & F. Görmar (Eds.), Regional and Local Development in Times of Polarisation, New Geographies of Europe (pp. 97-119). Chaltenham, UK: Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography, Palgrave Macmilan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978.-931-3-1190-1_5.

Kemp, R., Loorbach, D., & Rotmans, J. (2007). Transition management as a model for managing processes of co-evolution towards sustainable development. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 14(1), 78-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504500709469709