Received 10 September 2019; Revised 12 February 2020, 25 March 2020, 29 May 2020, 8 December 2020; Accepted 15 December 2020.

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode).

Ximena Alejandra Flechas Chaparro, Ph.D. student. Faculty of Economics, Administration, and Accounting, University of São Paulo, Brazil. Avenida Professor Luciano Gualberto, 908 - Butantã - São Paulo/SP - 05508-010, Brazil, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Ricardo Kozesinski, Ph.D. candidate. Faculty of Economics, Administration, and Accounting, University of São Paulo, Brazil. Avenida Professor Luciano Gualberto, 908 - Butantã - São Paulo/SP - 05508-010, Brazil, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Alceu Salles Camargo Júnior, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics, Administration, and Accounting, University of São Paulo, Brazil. Avenida Professor Luciano Gualberto, 908 - Butantã - São Paulo/SP - 05508-010, Brazil, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

Purpose: Several scholars have pointed out that absorptive capacity (AC) is critical for the innovation process in large firms. However, many other authors consider startups as key drivers for innovation in the current global economy. Therefore, this article aims to identify how the concept of AC has been addressed in the new venture context. Methodology: A systematic literature review analyzing 220 papers published between 2001 and 2018. Findings: The systematic literature review identifies three clusters of research addressing AC in startups: Knowledge, Innovation, and Performance, along with the central authors of the discussion, the main contributions, theoretical references, and their future research agenda guidelines. Implications for theory and practice: This study contributes to the innovation and entrepreneurship literature by connecting the importance of AC and new venture creation, and providing a better understanding of how entrepreneurs could enhance their innovative processes. Originality and value: Based on the analysis of the literature review, a framework that differentiates knowledge acquisition strategies for new ventures was created. The framework categorizes the strategies according to the knowledge source (i.e., internal or external) and the degree of intentionality (i.e., formal or informal).

Keywords: innovation, absorptive capacity, startups, new ventures, entrepreneurship

INTRODUCTION

Absorptive capacity (AC) is defined by Cohen and Levinthal (1990) as the ability to recognize, identify, assimilate and exploit new external information, and is considered to be critical for the innovation process. Zahra and George (2002, p. 186) defined AC as a “set of organizational routines and processes” including acquisition (to identify and obtain external knowledge), assimilation (to interpret and understand the information obtained), transformation (to integrate and combine existent knowledge with the newly acquired), and exploitation (the application of new knowledge for commercial ends). This ability involves renewing routines, practices, technological paths (March, 1991; McGrath, 2001), but in particular, it involves a learning process (Lane, Koka, & Pathak, 2006).

Previous works have addressed extensively how organizations might benefit from AC. For instance, Patterson and Ambrosini (2015) explored how AC could be configured to support research activities in biopharmaceutical firms, Engelen and colleagues (2014) identified how AC contributes to the strengthening of the entrepreneurial orientation and a firm’s performance relationship, and Lis and Sudolska (2015) studied what role AC plays in organizational growth and competitive advantage. The large number of theoretical and empirical publications addressing the AC construct over the past 30 years has also led to a number of literature reviews with different aims, such as revalidating and reconceptualizing the construct (e.g., Lane et al., 2006; Zahra & George, 2002), identifying major discrepancies among AC’s theoretical perspectives (e.g., Volberda, Foss, & Lyles, 2010), and analyzing the multifaceted dimensions of AC literature (e.g., Apriliyanti & Alon, 2017).

However, unlike these past reviews, in the present study, we propose to analyze AC in the context of new ventures, mainly due to two factors. First, because several authors have argued that startups are better suited to develop radical innovation (Bower & Christensen, 1995; Edison, Smørsgård, Wang, & Abrahamsson, 2018; Spencer & Kirchhoff, 2006). According to Giardino et al. (2014, p. 28), startups are entities “exploring new business opportunities, working to solve a problem where the solution is not well known and the market is highly volatile.” These organizations are characterized by a lack of resources, rapid evolution, small teams, little working experience, third-party dependency, and work under several uncertainties (Giardino et al., 2014). Despite the shortcomings associated with the scarcity of resources and experience (Ambos & Birkinshaw, 2010), these firms are able to launch innovative products and become a ‘game-changer’ in traditional industries, putting incumbent firms under pressure (Edison et al., 2018; Sirén, Hakala, Wincent, & Grichnik, 2017). Second, because, despite being game-changers, startups operating in technology-intensive industries suffer the permanent threat of premature obsolescence since –and considering the high level of uncertainty– these companies often bet on ‘failed technologies’ (i.e., those technologies that result not to be the ones adopted by the market (Eggers, 2012) and to survive, they must revamp their knowledge to adjust their solutions for which the AC may be crucial. Therefore, we identified a necessity to analyze AC literature within the context of new ventures in order to better understand which topics have been studied in this regard, and try to identify which aspects can be extracted from the main findings to contribute to some extent to the improvement of entrepreneurs’ processes of knowledge renewal and innovation.

The aim of our research is to determine how the concept of AC has been addressed in the new venture context by identifying the clusters of research, the main authors, and findings. To this end, we proceeded to conduct a systematic literature review analyzing 220 papers published between 2001 and 2018. Three clusters of research regarding the importance of AC in the new venture context were identified: Knowledge, Innovation, and Performance. In addition, the central authors of the discussion were reviewed, including their main contributions, theoretical references, and future research agenda.

The text is structured as follows: section 2 reviews the concepts and discussions about dynamic capabilities and new ventures, followed by the methodology in section 3. Our results are presented in section 4, including the bibliometric and content analyses. In section 5, we discuss the findings, and the last section contains the conclusions and suggestions for future research.

LITERATURE BACKGROUND

Authors such as Zahra and George (2002) and Engelen et al. (2014) have recognized AC as a dynamic capability. Dynamic capabilities (DC) enable the firm to evolve and positively influence its competitive advantage (Zahra & George, 2002, p. 185). Given that the present study seeks to connect concepts from the strategic management (i.e., AC and DC) and entrepreneurship fields, it is important to discuss in which way this interaction could be addressed considering the still ongoing debate about these concerns (Arend, 2014). Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (1997, p. 516) defined DC as “the firm’s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments.” DC is tied to the resource-based theory, in which firms’ differences, such as resources, skills or endowments, are key aspects that help companies to create a sustainable competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). However, DC complements the resource-based theory by providing the abilities for controlling, configuring, and reconfiguring the resources for long-term survival.

According to Teece et al. (1997), resources and assets are arranged in integrated groups of individuals that perform the firms’ activities or routines. In other words, through functions, routines, and competences, firms take advantage of their resources. However, differently from incumbent firms, new ventures lack functions and routines, so they need to rely broadly on team members’ and entrepreneurs’ idiosyncratic knowledge to operate (Bergh, Thorgren, & Wincent, 2011). In this regard, literature offers some examples of how DC has been addressed focused on individuals. For instance, Teece (2012) points out that there is a group of DC that is based on the individual “skills and knowledge of one or a few executives rather than on organizational routines” (Teece, 2012, p.1). According to the author, capabilities are built jointly by individual skills and collective learning originating from employees working together. In addition, the author notes that entrepreneurial management, besides being concerned about the improvement of existent routines, is more about creating new ones and figuring out new opportunities. Finally, Teece mentioned that the dependency on individual skills usually fades over time after five or ten years.

The individual approach in DC is associated with the concept of micro-foundations, which are one of the aspects that undergird the capabilities. According to Teece (2007, p. 1319), micro-foundations are the mechanisms through which sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring capacities operate; these include “the distinct skills, processes, procedures, organizational structures, decision rules, and disciplines.” Certainly, all these mechanisms widely depend on individual cognition (Helfat & Peteraf, 2015) and individuals’ extant knowledge (Teece, 2007). Helfat and Peteraf (2015) suggest that individual cognitive capabilities may mediate the relationship between changes in the organizational environment and strategic changes, and, therefore, individuals (by the effect of their own capacities) can reshape their organizations.

Several scholars have also discussed DC from the entrepreneurship perspective (for instance, Arend, 2014; Arthurs & Busenitz, 2006; Boccardelli & Magnusson, 2006; Newbert, 2005; Zahra, Sapienza, & Davidsson, 2006). These works offer different alternatives to connect both of the research strands (i.e., DC and entrepreneurship). For instance, Newbert (2005) proposes the new firm formation process as a dynamic capability, based on a random sample of 817 entrepreneurs; he concludes that there is evidence to support that new firm creation meets the DC conditions placed by Eisenhardt and Martin (2000) (i.e., identifiable, unique, deals with market dynamism, and is affected by learning). Arthurs and Busenitz (2006) set out that after the opportunity identification, when entrepreneurial leadership starts to transition to a more formal type of management, new ventures need to develop new skills –as mentioned by Teece (2012)– through the usage of DC. Furthermore, Arend (2014) found out that most entrepreneurial ventures have been created based on DC from the beginning, and mainly on an individual level.

RESEARCH METHODS

With the aim of determining how the concept of AC has been addressed in the startups’ context, we conducted a systematic literature review (SLR). This methodology is a rigorous and well-defined approach that enables the identification of the current knowledge and what is known about a given topic (Boell & Cecez-Kecmanovic, 2015). Following Denyer and Neely (2004), we endeavored to develop an accurate process considering the planning, the use of explicit and reproducible selection criteria, and an analysis procedure. Figure 1 summarizes our systematic review process.

Figure 1. Summary of the systematic review process

During the planning phase, we determined the purposes of the research and its most important aspects. Our main goal was to identify how past research employed AC in an entrepreneurship and startups context. We did not limit the research to any specific time frame and only peer-reviewed articles were included. We conducted a search in September 2018 on the Web of Science (WOS, Clarivate Analytics) database since it is one of the most complete peer-review journal repositories on social sciences (Crossan & Apaydin, 2010). We defined two subject areas, “Management” and “Business,” and searched in all the indexes provided on WOS (SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, and ESCI). Given the wide diversity of terms and morphological variety to refer to a “recently created innovative company”, we applied the following Boolean search keywords: “((absorptive capacity) AND (“startup” OR “start-up” OR “start up” OR “new firm*” OR “NTBF” OR “new venture” OR “entrepreneur*”)) in the Topic (title, keywords or abstract) category.

Sampling process

The search returned 358 papers. An exclusion filter was applied to select only documents that address AC in the context of entrepreneurship, on the basis of a thorough reading of titles and abstracts. In order to minimize bias in this filter parameter, the documents were reviewed in two rounds by the researchers. The final search process yielded 220 documents published between 2001 and 2018.

Data analysis

We performed bibliometric and statistical analyses to provide an overview of the literature, including the publications per year and the main journals. We also carried out a network analysis employing the VOSviewer 1.6.9 Software. The data was extracted directly from WOS, including all the information items (e.g., title, abstract, keywords, publication year, cited references, etc.). Then, we manually removed the non-related documents using Microsoft Excel. These data were exported to a text file (*txt) and imported to VOSviewer to create the co-occurrence and co-citation networks in order to identify the main theoretical references and central discussions. We used the default settings of the program, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Default settings of VOSviewer

|

Parameter |

Default settings |

|

Counting method |

Full counting |

|

Method of normalization |

Association strength |

|

Layout of attraction repulsion |

2 |

|

Layout of repulsion |

0 |

|

Clustering resolution |

1.00 |

|

Minimum size of clusters |

1 |

|

Merging small clusters |

Switched on |

Based on the all keywords co-occurrence network, we identified three clusters of lines of research: knowledge, innovation, and performance. Afterward, we proceeded to classify all the papers of our database into these three clusters using Microsoft Excel. After reading the documents, we selected the most relevant articles that matched the research goal and the clustering parameter as well. A total of 50 papers satisfied these parameters and are discussed in the content analysis. The documents were manually coded using the Mendeley Desktop 1.19 software and Microsoft Excel, considering the following aspects: 1) Authors, 2) Year of publication, 3) Journal, 4) Type of article, 5) Aim of research, 6) Relevance of absorptive capacity, 7) Methodology, sample, and variables, 8) Findings, and 9) Future research agenda. We provide a detailed explanation of the coding process in Appendix A (Knowledge cluster; Innovation cluster; Performance cluster.)

RESULTS

Bibliometric and descriptive analyses

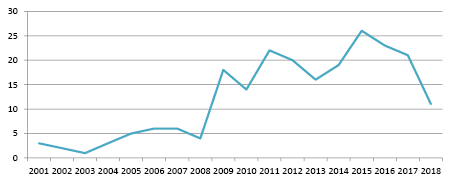

Figure 2 shows the evolution of publications over time. It is observed that the earliest paper in the sample was published in 2001; from 2009, there is an increase in the number of publications, reaching a peak in 2015 with 26 publications. The 220 articles are distributed over 77 journals. Table 2 shows the most representative journals accounting for about 60 percent of the sample.

Figure 2. Number of papers published on AC and Startups over time

Table 2. Most common outlet journals

|

Abbreviation |

Full Title |

Articles |

|

JBV |

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS VENTURING |

16 |

|

SEJ |

STRATEGIC ENTREPRENEURSHIP JOURNAL |

12 |

|

ET&P |

ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY AND PRACTICE |

11 |

|

JSBM |

JOURNAL OF SMALL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT |

11 |

|

IBR |

INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS REVIEW |

10 |

|

RP |

RESEARCH POLICY |

10 |

|

SBE |

SMALL BUSINESS ECONOMICS |

9 |

|

ERD |

ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT |

7 |

|

JWB |

JOURNAL OF WORLD BUSINESS |

7 |

|

JTT |

JOURNAL OF TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER |

6 |

|

R&DMANAGE |

R & D MANAGEMENT |

6 |

|

SMJ |

STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT JOURNAL |

6 |

|

IJTM |

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF TECHNOLOGY MANAGEMENT |

5 |

|

JMS |

JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES |

5 |

|

EMJ |

EUROPEAN MANAGEMENT JOURNAL |

4 |

|

IMM |

INDUSTRIAL MARKETING MANAGEMENT |

4 |

|

ISBJ |

INTERNATIONAL SMALL BUSINESS JOURNAL |

4 |

|

Total: |

133 |

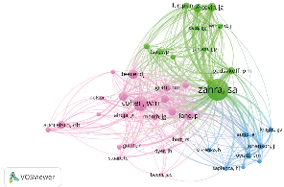

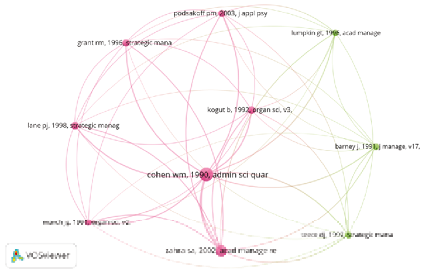

In order to identify the central authors, we performed a co-citation analysis based on cited authors. This analysis builds a network based on the citation link (where one item cites the other). We set this parameter to a minimum of “40 citations of an author,” resulting in 41 central authors, as seen in Figure 3.

The map shows the number of citation links (represented by the number of lines) and the link strength (represented by the distance between items), which refers to a similarity measure normalized by the association strength (van Eck & Waltman, 2010). Zahra S. is the author with the most citation links (412) and total link strength (6082) followed by Cohen W. with 233 and 3067, respectively. The number of links and total link strength of the central authors is displayed in Table 3.

Figure 3. Co-citation author network

Table 3. Citation link and link strength of the co-citation author network

|

Author |

Citation link |

Link strength |

Author |

Citation link |

Link strength |

|

Acs Z. |

58 |

841 |

Kogut B. |

97 |

1653 |

|

Ahuja G. |

67 |

1103 |

Lane P. |

121 |

1879 |

|

Audretsch D. |

101 |

1290 |

Lumpkin G. |

66 |

1261 |

|

Autio E. |

56 |

1100 |

March J. |

72 |

1214 |

|

Barney J. |

54 |

874 |

McDougall P. |

44 |

827 |

|

Baum J. |

40 |

605 |

Miller D. |

95 |

1747 |

|

Burt R. |

44 |

823 |

Nelson R. |

47 |

727 |

|

Chesbrough |

41 |

500 |

Nonaka I. |

69 |

1097 |

|

Cohen W. |

233 |

3067 |

Oviatt B. |

69 |

1366 |

|

Coviello N. |

40 |

829 |

Podsakoff P. |

87 |

1537 |

|

Covin J. |

105 |

2012 |

Rothaermel F. |

51 |

709 |

|

Dess G. |

42 |

771 |

Sapienza H. |

53 |

984 |

|

Dyer J. |

48 |

947 |

Shane S. |

116 |

1694 |

|

Eisenhardt K. |

99 |

1487 |

Shumpeter J. |

46 |

728 |

|

Grant R. |

86 |

1469 |

Stuart T. |

42 |

603 |

|

Gulati R. |

51 |

975 |

Teece D. |

123 |

1888 |

|

Helfat C. |

61 |

995 |

Tsai W. |

72 |

1278 |

|

Hitt M. |

58 |

1015 |

Wiklund J. |

58 |

1208 |

|

Jansen J. |

49 |

887 |

Yli-renko H. |

41 |

814 |

|

Johanson J. |

74 |

1444 |

Zahra S. |

412 |

6082 |

|

Knight G. |

47 |

914 |

Top 10 Co-citation references network

We also built another co-citation network but based on the analysis of cited references to find commonalities in the theoretical background. The resultant network, exhibited in Figure 4, contains the top ten cited references. We present a brief description of these publications below.

Figure 4. Top 10 Co-citation references network

Cohen and Levinthal (1990, p. 128) introduced the term AC to refer to the “ability of a firm to recognize the value of new, external information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends.” The authors argue that AC is critical to the firms’ innovative capabilities, and it requires prior related knowledge to evaluate and utilize the outside new knowledge. Similarly, March (1991, p. 83) suggested that knowledge “makes performance more reliable,” and learning and technological changes might improve competitive advantage. In this study, March popularized the idea that firms must enhance their technological explorative and exploitative abilities and look for a balance between them in order to ensure survival and achieve better performance. In this regard, Barney (1991), aiming for a more comprehensive understanding of sustained competitive advantage, proposed that some resources and characteristics (such as heterogeneity, valuable, rareness, or inimitableness) are crucial for a firm’s competitiveness, and they may vary over time.

To Kogut and Zander (1992), one central aspect of the competitive dimension is the ability to transfer knowledge within the firm. The authors drew on the perspective that organizations are repositories of tacit and explicit knowledge, skills, and social networks, which enable companies to learn new abilities by recombining their existent resources and capabilities. In this same vein, Grant (1996) explores how to integrate the specialized knowledge of individuals into firms. Drawing on the resource-based theory, Grant (1996, p. 110) conceptualizes the knowledge-based view as a new perspective to understand a company, placing knowledge as “the most strategically important of the firm’s resources.” Additionally, he identified the key characteristics of knowledge in order to create value: transferability (the capacity of transference across individuals), capacity of aggregation (the potential to add new knowledge to the existing one), and appropriability (the ability of the owner of a resource to receive a return).

Alternatively, Lumpkin and Dess (1996) explore the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and firm performance. The authors defined EO as the practices, processes, and decision-making activities that lead the firm to enter new or existing markets, and is characterized by the “propensity to act autonomously, a willingness to innovate and take risks, and a tendency to be aggressive toward competitors and proactive relative to marketplace opportunities” (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996, p. 137).

In order to address the question of how firms achieve sustained competitive advantage, Teece et al. (1997) proposed the dynamic capabilities concept. As discussed in section 2, this perspective “emphasizes the development of management capabilities, and difficult-to-imitate combinations of organizational, functional and technological skills” (Teece et al., 1997, p. 510). Similarly, from the basis that not all firms have equal chances to acquire knowledge, Lane and Lubatkin (1998) reconceptualized the construct of AC as a dyad-level construct and established some conditions for this interaction to occur: the specific type of knowledge, similarities in practices, logic and organizational structure, and familiarities between the firms. Zahra and George (2002) also reconceptualized AC as a dynamic capability related to knowledge creation and exploitation in order to gain sustained competitive advantage. Additionally, they proposed that AC is built upon two capacities: potential capacity (knowledge acquisition) and realized capacity (knowledge transformation and exploitation). Ending this top ten references network, Podsakoff et al. (2003) present an important methodological review about biases in behavioral research methods that are often employed and cited by AC researchers. The authors summarized the most common sources of method biases, their effects, and techniques to control them.

Content analysis

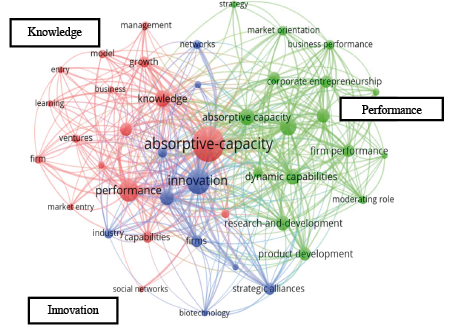

Finally, we created the co-occurrence map using all keywords as the unit of analysis, as presented in Figure 5. We used the default parameter of a minimum of 10 occurrences of a keyword (Eck & Waltman, 2018). According to Gomes et al. (2016), keywords maps are widely used by researchers and help to establish a general idea on a certain subject. From this map, three clusters of lines of research addressing AC in startups were identified: knowledge (26 articles), innovation (11 articles), and performance (13 articles). Based on these clusters, we performed our data analysis and identified the following codes: 1) Authors, 2) Year of publication, 3) Journal, 4) Type of article, 5) Aim of research, 6) Relevance of absorptive capacity, 7) Methodology, sample, and variables, 8) Findings, and 9) Future research agenda.

Figure 5. Co-occurrence map using all keywords

New knowledge is an essential input factor for innovation and new firm’s progress (Mueller, 2006; Prashantham & Young, 2011; Sullivan & Marvel, 2011; McKelvie, Wiklund, & Brattström, 2018; Bingham & Davis, 2012) by offering the possibility of renewing existent skills, technological paths, and developing innovative capabilities to improve competitive advantage and stimulate growth (Zahra, Filatotchev, & Wright, 2009; Agarwal, Audretsch, & Sarkar, 2010). Several authors recognize R&D as a major vehicle to acquire new knowledge (Acs, Braunerhjelm, Audretsch, & Carlsson, 2009; Mueller, 2006). However, very often, new and small firms do not have the resources to structure an R&D department; thus, partnerships with institutions such as universities or research laboratories are crucial to develop new knowledge (Hayton & Zahra, 2005; Hayter, 2013; Carayannis, Provance, & Grigoroudis, 2016; Dai, Goodale, Byun, & Ding, 2018). Sullivan and Marvel (2011) emphasize that technology and market knowledge is highly important to achieve positive results and enhance the innovative process. In any case, direct inter-personal contacts and proximity to the environment are useful to access knowledge (including tacit knowledge) faster and more successfully (Mueller, 2007, p. 356).

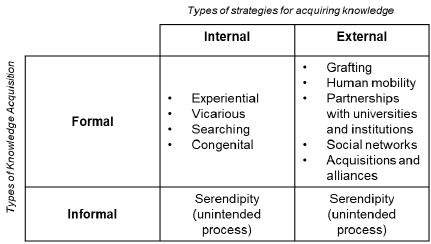

Based on Huber (1991), De Clercq et al. (2012) categorized knowledge acquisition (KA) into five types: experiential learning (learning from experience), vicarious learning (learning by observing others), searching (learning by searching for specific information), grafting (learning by incorporating entities that possess knowledge), and congenital learning (drawing on intrinsic knowledge gained from founders or personal experience). Differently, Carayannis, Provance, and Givens (2011) proposed to classify KA into two groups regarding the form of acquisition: (1) formal KA and arbitrage (referring to the intended ability to manage and apply knowledge for a specific purpose), and (2) informal KA and serendipity (referring to the unintended rewards of enabling knowledge from different sources).

Friesl (2012) identified four knowledge acquisition strategies: “low key” in which there are low levels of collaborative and internal learning and low performance as well; “mid-range,” where the emphasis is on collaborative and market-based learning but low levels of internal learning; “focus,” where the firms’ efforts concentrate on both collaborative and internal learning; and “explorer,” in which firms have high mean values for all knowledge acquisition categories (i.e., collaborative, internal, and market-based learning). In this latter group, firms have a particular interest in renewing their knowledge base in order to achieve the highest level of performance.

We identified three recurrent research topics in the present cluster: entrepreneurial internationalization (EI), spin-offs, and identification of opportunities. The first topic, EI, explores how new firms go about looking to expanding their activities into foreign markets (De Clercq et al., 2012; Bruneel, Yli-Renko, & Clarysse, 2010; Yu, Gilbert, & Oviatt, 2011). Considering that entering foreign markets might entail the obsolescence of existing knowledge and capabilities, to acquire new knowledge becomes crucial to successful internationalization (De Clercq et al., 2012; Prashantham & Young, 2011; Bruneel et al., 2010; Fernhaber, McDougall-Covin, & Shepherd, 2009; Tolstoy, 2009). Therefore, AC emerges as a cornerstone for new venture survival and a critical factor for growth (Mueller, 2007; Qian & Acs, 2013; Moon, 2011). Some studies point out that networks and alliances may enable and accelerate initial commercial activities in new markets (Bruneel et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2011; Sullivan & Marvel, 2011; Perez, Whitelock, & Florin, 2013), and support the absence of in-house translators of new knowledge as suggested in AC theory (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

The second topic of research studies is the creation of spin-offs as a vehicle to commercialize new knowledge developed in public research institutes, in large incumbent firms, or in universities (Knockaert, Ucbasaran, Wright, & Clarysse, 2011; Qian & Acs, 2013; Hayter, 2013; Patton, 2014). Qian and Acs (2013, p. 191) argued that the level of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship depends not only on the speed or level of knowledge creation, but also on entrepreneurial absorptive capacity (EAC), defined as the “ability of an entrepreneur to understand new knowledge, recognize its value, and subsequently commercialize it by creating a firm.” Different from Cohen and Levinthal’s AC concept, EAC focuses on the entrepreneur’s abilities –not on the firm’s abilities– and involves the capacity to build a new business.

The third and last topic considers AC as a means to identify opportunities and enhance the firm’s performance (McKelvie et al., 2018; Saemundsson & Candi, 2017). Due to the fact that existing knowledge base might become obsolete within a short period of time, new ventures must intensively promote the search for novel knowledge, primarily in market and customer knowledge (McKelvie et al., 2018). Regarding the principles of AC set by Cohen and Levinthal (1990), to absorb new knowledge requires certain existent abilities. This is probably a challenge for startups because, in many cases, they are building new markets and customers have not been identified at all. In this respect, McKelvie et al. (2018) suggest that new ventures may not over-rely on external knowledge acquisition, especially when the firm works in a highly dynamic sector. Furthermore, Saemundsson and Candi (2017, p. 43) proposed to divide potential AC into “problem absorptive capacity, i.e. the ability to identify and acquire knowledge of the goals, aspirations and needs of current and potential customers, and solution absorptive capacity, i.e. the ability to identify and acquire external knowledge of solutions to fulfill them.” The authors found out that changes in problem absorptive capacity are a stronger trigger for identification of new opportunities than changes in solution absorptive capacity.

Innovation cluster

According to Dushnitsky and Lenox (2005a, 2005b), Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) carry a potential innovative benefit. The authors suggest that the greater the firm’s AC, the greater the firm’s investment in entrepreneurial new ventures and, therefore, the firm’s innovation rate (Dushnitsky & Lenox, 2005b, 2005a). Nevertheless, the role of AC is not restricted to an enabler of innovation. In fact, access to new information provided by CVC can improve the AC of the firms (Wadhwa & Hall, 2005), although this strategy may limit the knowledge created. Similarly, Lee, Kim, and Jang (2015) argue that the firm’s knowledge diversity enables corporate investors to acquire and maximize useful knowledge.

On the other hand, Winkelbach and Walter (2015) found out that prior knowledge held by the firms has a non-significant effect on value creation. Knowledge creation and knowledge-related learning capabilities (which are moderated by AC) enable firms to deal with dynamic environments to create value and develop innovation. Scholars approach the pursuit of new knowledge by firms to promote innovation in different ways. For instance, human mobility across national borders may foster knowledge creation (Liu, Wright, Filatotchev, Dai, & Lu, 2010). The new knowledge may come from scientists and engineers that return from abroad to start up a new venture in their native countries (Liu et al., 2010). Regarding the type of source of new knowledge (i.e., internal or external), Kamuriwo, Baden-Fuller, and Zhang (2017) point out that external knowledge development is more associated with breakthrough innovations and with a faster time-to-market.

Nevertheless, existing literature suggests that there are some setbacks related to knowledge acquisition and innovation. Marvel (2012) pointed out that sometimes knowing less is better to create innovation. His findings suggest that acquiring the knowledge of ways to serve markets is “negatively associated with innovation radicalness” (Marvel, 2012, p. 464). Therefore, the less knowledge about existing offerings in the market and how they work, the greater the chances for developing breakthrough innovations.

Knowledge acquisition can also stem from universities in the form of academic entrepreneurship, technology transfer, and research commercialization. Using the AC perspective, two multiple case studies explored the Proof of Concept (PoC) process within a University Science Park Incubator (UK) and provided evidence that AC plays a crucial role in obtaining commercial outcomes (McAdam, McAdam, Galbraith, & Miller, 2010; McAdam, McAdam, & Brown, 2009).

Finally, network market orientation is found to make a significant contribution to the development of AC in international new ventures. Monferrer, Blesa, and Ripollés (2015) showed that network market orientation facilitates the development of dynamic adaptive and absorptive capabilities, which influence their capacity to develop innovative, dynamic capabilities.

Performance cluster

AC might also moderate the firm’s performance (Nielsen, 2015; Zahra & Hayton, 2008). In our review, we found two perspectives of performance: addressed as a capability to innovate and as a financial output. Typically, firms engage in activities such as acquisitions, alliances and CVC when pursuing growth and profitability. Yet, it is not completely clear how these activities may influence the firm’s performance. To that end, Zahra and Hayton (2008) suggest that AC moderates this relationship. According to their findings, after studying 217 global manufacturing firms, the investments made for building AC positively influence the firm’s performance benefits derived from international venturing. Conversely, Benson and Ziedonis (2009, p. 330) argue that “internal technological capabilities remain a critical determinant of success in innovation-driven acquisitions.” A limit on CVC investment is imposed by the acquirer’s total R&D expenditures, and beyond this limit, the firm’s performance starts to improve at a diminishing rate. Wales, Parida, and Patel (2013) posit that the relationship between AC and financial performance is mediated by Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) referred to as the “strategy-making practices, management philosophies, and firm-level behaviors that are entrepreneurial in nature” (Anderson, Covin, & Slevin, 2009. p. 220).

Based on an individual perspective of AC, Nielsen (2015) proposes that individuals with higher levels of education have also higher absorptive and learning capacities that leverage the likelihood of firms’ survival and growth. Additionally, some authors (for instance, Rhee, 2008; Witt, 2004) claim that, in general, the social network represents the theoretical lenses used to investigate performance and startup success. Surprisingly, Rhee (2008) found that social networks of the startup’s team members do not help their ventures to reap superior performance. By comparing university and corporate spin-offs, Clarysse, Wright, and Van de Velde (2011) revealed that different characteristics in the technological knowledge base (e.g., specificity, newness, or tacitness) influence the spin-off’s performance and growth. According to Simsek and Heavey (2011), corporate entrepreneurship impacts positively the knowledge-based human, social, and organizational capital and is also positively associated with the firm’s performance (i.e., profitability and growth).

Considering international sales performance, Javalgi, Hall, and Cavusgil (2014) argue that AC has a positive relation with customer-oriented selling and performance in international B2B settings. Furthermore, Un and Montoro-Sanchez (2011) define performance as the development of new technological capabilities through investments in R&D. Their research uncovered that the prior capabilities enable the firm to develop new technological ones. In another approach, Zheng, Liu, and George (2010) suggest that a key performance indicator is the valuation or market value, which is influenced by the innovative capability and the network heterogeneity of the firms.

Dynamic and operating capabilities must interact to enable entrepreneurship (Newey & Zahra, 2009). AC may be a key knowledge-based mechanism, which connects learning at both product development and portfolio planning levels. Finally, Deeds (2001) suggests that there is a positive relationship between a high technology venture’s R&D intensity, technical capabilities, and AC and the amount of entrepreneurial wealth created by the venture.

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the issues raised in the previous section, we observed a relationship between the three clusters: firms employ and develop their AC in order to identify and transform new knowledge into innovation projects, which in turn leads to performance improvement and growth (see figure 6). This relationship is confirmed by authors such as Mueller (2006), who emphasizes the contribution of new knowledge and knowledge exploitation as valuable inputs for economic regional growth. Moreover, Zahra et al. (2009) reinforce the idea that for a startup to grow, it is necessary to revamp its skills, replace its dated capabilities, and build up new ones. In this regard, AC plays an important role as an enabler for integrating knowledge from different sources. Another approach that supports the relationship presented in Figure 6 is the innovation capability because this construct integrates the creation or appropriation of new knowledge, the transformation of that knowledge into new or improved products, and the firm’s progress or performance enhancement (Aas & Breunig, 2017).

Figure 6. Relationship between the three clusters

We identify that there are open discussions about different aspects. The first is the favorability of certain types of knowledge sources (i.e., internal or external) for developing innovations. McKelvie et al. (2018) argue that in highly dynamic environments, the payoff attributed to investments in externally acquired knowledge is not significant. In this same vein, Marvel (2012) found out that knowing less is better to create innovation; the less knowledge about existing offerings in the market, the greater the chances for developing breakthrough innovations. Conversely, Kamuriwo et al. (2017) claim that external knowledge development is more associated with breakthrough innovations and with a faster time-to-market. The second aspect is the role of prior knowledge. On the one hand, Winkelbach and Walter (2015) identify the sole reliance on prior knowledge may foster traps and hinder the ability to foresee opportunities. On the other hand, Un and Montoro-Sanchez (2011) argue that prior stock of knowledge and capabilities enable the development of new ones and thus ensure value creation. Finally, there are some mismatches related to the volume of new knowledge required for developing breakthrough innovations; in the discussion set out by Marvel (2012) it is not clear whether large amounts of knowledge are favorable or not in the development of radical innovation products.

There are three major reasons for companies to engage in knowledge renewal: to address the evolving character of environmental conditions and customer’s preferences for enabling growth (Marvel, 2012; Perez et al., 2013; Zahra et al., 2009), to enter into foreign markets (i.e., internationalization) (Prashantham & Young, 2011; Rhee, 2008; Tolstoy, 2009), and to identify entrepreneurial opportunities (McKelvie et al., 2018; Saemundsson & Candi, 2017). Regarding the types of strategies for knowledge acquisition, we identified two of the former: formal and informal (Carayannis et al., 2011), and two of the latter: internal and external (Friesl, 2012) (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Types and strategies of knowledge acquisition

Internal–formal strategies comprise four categories: experiential learning (learning from experience), vicarious learning (learning by observing others, for instance, customers or competitors), searching (learning by searching for specific information), and congenital learning (drawing on intrinsic knowledge gained from founders or personal experience) (De Clercq et al., 2012). On the other hand, external–formal strategies include grafting (learning by incorporating entities that possess knowledge) (De Clercq et al., 2012), human mobility (i.e., knowledge transfer from the exchange of experience as a result of human mobility across national borders) (Liu et al., 2010), partnerships with universities and technology institutions (Clarysse et al., 2011; Mueller, 2006), social networks (Newey & Zahra, 2009; Witt, 2004), and acquisitions and alliances (Dai et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2011; Zahra & Hayton, 2008). Both internal–informal and external–informal are based on the serendipity approach, which refers to the unintended rewards of enabling knowledge from different sources (Carayannis et al., 2011).

From the review, we highlight three recommendations for startups concerning absorptive capacity. First, considering the resource limitations of startups, developing partnerships with institutions such as universities or research laboratories could enhance the capacity for identifying and gathering new knowledge (Hayton & Zahra, 2005; Hayter, 2013). Second, networking, direct inter-personal contacts, and proximity to the environment are useful to access knowledge and become crucial to successful internationalization (De Clercq et al., 2012; Mueller, 2007). Finally, in order to improve the opportunities recognition, new firms should emphasize the problem absorptive capacity, in other words, in identifying and acquiring knowledge related to the aspirations and needs of current and potential customers, instead of on existent solutions (Saemundsson and Candi, 2017)

Additionally, some common issues among researchers were identified. First, there is wide adoption of the definition of AC proposed by Cohen and Levinthal (1990) as the mechanism through which firms identify, acquire, and exploit new knowledge in order to achieve more sustainable levels of growth. Second, internal capabilities enable the firm to transform new knowledge into value. Third, intellectual property rights may inhibit the openness to acquire external knowledge and limit the offers to receive venture capital.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH AGENDA

The purpose of this paper was to identify how the concept of AC has been addressed in the new venture context. We selected 220 documents and applied a systematic literature review method that evidenced three clusters of research: knowledge, innovation, and performance. We concluded that the AC construct first conceived by Cohen and Levinthal in 1990 still stands as an important theoretical lens. Several scholars used the concept in its original context, but others extended it to other research fields, such as the role of AC in universities and research institute spin-offs, corporate venture capital, entrepreneurs’ networks, and as a crucial factor to new venture performance.

Bibliometric analyses showed an increasing interest in AC in the context of new firms. In spite of the earliest paper being published in 2001, the main concepts (which currently prevail) were proposed during the decades of the 1990s (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Grant, 1996; Kogut & Zander, 1992; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996) and the early 2000s (Zahra & George, 2002). We identify three inter-related clusters of research regarding the importance of AC in the new venture context: knowledge, innovation, and performance. The relationship between the clusters reflects how firms employ and develop their AC in order to identify and transform new knowledge into innovation projects, which in turn leads to performance improvement and growth.

Content analysis revealed three main concerns related to knowledge obsolescence: growth and dynamic environment and markets, entrepreneurial opportunities, and internationalization. Firms can apply several strategies, internal or external, in order to acquire knowledge, and also might follow both formal and informal processes to address the strategies.

Regarding future research, we identify three avenues exhibit in Table 4. The first avenue contemplates AC from the individual perspective to follow the multilevel approach set by some management areas, which started with the firm level, business unity, project, and ended on an individual level (e.g., uncertainty management; Gomes et al., 2019). The second avenue centers on bibliometric analysis and literature reviews aiming to identify pivotal studies, which have changed or incorporated content into the AC literature. Finally, the third avenue is related to the strategies for knowledge acquisition in order to clarify the conflicting aspects identified in our content analysis.

Table 4. New avenues for future research

|

Potential research questions |

|

|

The individual perspective |

|

|

Bibliometric analysis and literature review |

|

|

Strategies for KA |

|

In addition, we identify some suggestions from the literature: empirical research for validating models or propositions, considering larger samples, longitudinal analysis, different sectors, cultures, and regions. Furthermore, the authors propose to conduct further studies analyzing the types of networks, the interdependencies between the innovation strategies, public policy on innovation, and incorporating different measures of AC.

We contribute to the innovation and entrepreneurship literature in different ways. First, we have connected the importance of AC and new venture creation, to provide a better understanding of how entrepreneurs could enhance their innovative processes. Second, we have established an overview of the existing literature on AC in startups, highlighting the main authors and drivers. Third, we have clustered the pertinent literature with distinct research themes regarding the entrepreneurial AC found in our systematic review and have also proposed a framework that differentiates knowledge acquisition strategies for new ventures. Finally, we have suggested future research opportunities on entrepreneurship and absorptive capacity.

The results also allow us to identify some practical implications. The analyzed literature suggests that there are certain strategies that entrepreneurs may adopt in order to acquire and absorb new knowledge. We categorize these strategies according to the knowledge source (i.e., internal or external) and the degree of intentionality (i.e., formal or informal). This effort is aimed at persuading entrepreneurs and practitioners to bear in mind a wide range of strategies that mediate between acquiring knowledge and achieving growth objectives and expansion into new markets.

Finally, some limitations must be considered regarding the systematic literature review method. First, concerning the sampling procedures, the keyword selection, which includes only articles published in English and databases from one specific scientific citation indexing service, can limit the resulting sample. In addition, there is some subjectivity involved in the selection of articles for analysis; this is mainly because it relies on the authors’ interpretations from reading titles and abstracts. Furthermore, the concept of startups is not very precise. We noticed that it still remains ambiguous and unclear since it is defined differently among the authors. Therefore, it can be difficult to filter the sample in order to restrict the analyses to one specific type of firm.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) Foundation (a Brazilian research agency) under scholarship grants.

References

Aas, T. H., & Breunig, K. J. (2017). Conceptualizing innovation capabilities: A contingency perspective. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 13(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.7341/20171311

Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9157-3

Agarwal, R., Audretsch, D., & Sarkar, M. (2010). Knowledge spillovers and strategic entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(4), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.96

Ambos, T. C., & Birkinshaw, J. (2010). How do new ventures evolve? An inductive study of archetype changes in science-based ventures. Organization Science, 21(6), 1125–1140. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0504

Anderson, B. S., Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (2009). Understanding the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and strategic learning capability: An empirical investigation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 3(3), 218–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej

Apriliyanti, I. D., & Alon, I. (2017). Bibliometric analysis of absorptive capacity. International Business Review, 26(5), 896–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.02.007

Arend, R. J. (2014). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: How firm age and size affect the “capability enhancement-SME performance” relationship. Small Business Economics, 42(1), 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9461-9

Arthurs, J. D., & Busenitz, L. W. (2006). Dynamic capabilities and venture performance: The effects of venture capitalists. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(2), 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.04.004

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Benson, D., & Ziedonis, R. H. (2009). Corporate venture capital as a window on new technologies: Implications for the performance of corporate investors when acquiring startups. Organization Science, 20(2), 329–351. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0386

Bergh, P., Thorgren, S., & Wincent, J. (2011). Entrepreneurs learning together: The importance of building trust for learning and exploiting business opportunities. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0120-9

Bingham, C. B., & Davis, J. P. (2012). Learning sequences: Their existence, effect, and evolution. Academy of Management Journal, 55(3), 611–641. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0331

Boccardelli, P., & Magnusson, M. G. (2006). Dynamic capabilities in early-phase entrepreneurship. Knowledge and Process Management, 13(3), 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.255

Boell, S. K., & Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. (2015). Debating systematic literature reviews (SLR) and their ramifications for IS: A rejoinder to Mike Chiasson, Briony Oates, Ulrike Schultze, and Richard Watson. Journal of Information Technology, 30(2), 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2015.15

Bower, J., & Christensen, C. (1995). Disruptive technologies: Catching the wave. Harvard Business Review, (February), 1–17.

Bruneel, J., Yli-Renko, H., & Clarysse, B. (2010). Learning from experience and learning from others: How congenital and interorganizational learning substitute for experiential learning in young firm internationalization. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(2), 164–182. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.89

Carayannis, E. G., Provance, M., & Givens, N. (2011). Knowledge arbitrage, serendipity, and acquisition formality: Their effects on sustainable entrepreneurial activity in regions. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 58(3), 564–577. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2011.2109725

Carayannis, E. G., Provance, M., & Grigoroudis, E. (2016). Entrepreneurship ecosystems: An agent-based simulation approach. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(3), 631–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-016-9466-7

Clarysse, B., Wright, M., & Van de Velde, E. (2011). Entrepreneurial origin, technological knowledge, and the growth of spin-off companies. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6), 1420–1442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00991.x

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152.

Crossan, M. M., & Apaydin, M. (2010). A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1154–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00880.x

Dai, Y., Goodale, J. C., Byun, G., & Ding, F. (2018). Strategic flexibility in new high-technology ventures. Journal of Management Studies, 55(2), 265–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12288

De Clercq, D., Sapienza, H. J., Yavuz, R. I., & Zhou, L. (2012). Learning and knowledge in early internationalization research: Past accomplishments and future directions. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1), 143–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.09.003

Deeds, D. L. (2001). Role of R&D intensity, technical development and absorptive capacity in creating entrepreneurial wealth in high technology start-ups. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 18(1), 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0923-4748(00)00032-1

Denyer, D., & Neely, A. (2004). Introduction to special issue: Innovation and productivity performance in the UK. International Journal of Management Reviews, 5–6(3–4), 131–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-8545.2004.00100.x

Dushnitsky, G., & Lenox, M. J. (2005a). When do firms undertake R&D by investing in new ventures? Strategic Management Journal, 26(10), 947–965. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.488

Dushnitsky, G., & Lenox, M. J. (2005b). When do incumbents learn from entrepreneurial ventures?: Corporate venture capital and investing firm innovation rates. Research Policy, 34(5), 615–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.017

Eck, N. J. Van, & Waltman, L. (2018). VOSviewer Manual for VOSviewer version 1.6.9. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3402/jac.v8.30072

Edison, H., Smørsgård, N. M., Wang, X., & Abrahamsson, P. (2018). Lean internal startups for software product innovation in large companies: Enablers and inhibitors. Journal of Systems and Software, 135, 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2017.09.034

Eggers, J. P. (2012). Falling flat: Failed technologies and investment under uncertainty. Administrative Science Quarterly, 57(1), 47–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839212447181

Engelen, A., Kube, H., Schmidt, S., & Flatten, T. C. (2014). Entrepreneurial orientation in turbulent environments: The moderating role of absorptive capacity. Research Policy, 43(8), 1353–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.03.002

Fernhaber, S. A., McDougall-Covin, P. P., & Shepherd, D. A. (2009). International entrepreneurship: Leveraging internal and external knowledge sources. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 3(4), 297–320. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.76

Friesl, M. (2012). Knowledge acquisition strategies and company performance in young high technology companies. British Journal of Management, 23(3), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00742.x

Giardino, C., Unterkalmsteiner, M., Paternoster, N., Gorschek, T., & Abrahamsson, P. (2014). What do we know about software development in startups? IEEE Software, 31(5), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2014.129

Gomes, L. A. de V., Brasil, V. C., Reis de Paula, R. A. S., Facin, A. L. F., Gomes, F. C. de V., & Salerno, M. S. (2019). Proposing a multilevel approach for the management of uncertainties in exploratory projects. Project Management Journal, 50(5), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756972819870064

Gomes, L. A. de V., Facin, A. L. F., Salerno, M. S., & Ikenami, R. K. (2018). Unpacking the innovation ecosystem construct: Evolution, gaps and trends. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 136, 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.009

Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge based theory of frim. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 109–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/2486994

Hayter, C. S. (2013). Conceptualizing knowledge-based entrepreneurship networks: Perspectives from the literature. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 899–911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9512-x

Hayton, J. C., & Zahra, S. A. (2005). Venture team human capital and absorptive capacity in high technology new ventures. International Journal of Technology Management, 31(3/4), 256–274. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2005.006634

Helfat, C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2015). Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 36(6), 831–850. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2247

Javalgi, R. G., Hall, K. D., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2014). Corporate entrepreneurship, customer-oriented selling, absorptive capacity, and international sales performance in the international B2B setting: Conceptual framework and research propositions. International Business Review, 23(6), 1193–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.04.003

Kamuriwo, D. S., Baden-Fuller, C., & Zhang, J. (2017). Knowledge development approaches and breakthrough innovations in technology-based new firms. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 34(4), 492–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12393

Knockaert, M., Ucbasaran, D., Wright, M., & Clarysse, B. (2011). The relationship between knowledge transfer, top management team composition, and performance: The case of science-based entrepreneurial firms. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 35(4), 777–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00405.x

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3(3), 383–397.

Lane, P. J., & Lubatkin, M. (1998). Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning. Strategic Management Journal, 19(5), 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199805)19:5<461::AID-SMJ953>3.3.CO;2-C

Lane, P., Koka, B., & Pathak, S. (2006). The reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 833–863. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.22527456

Lee, Sang M; Kim, Taewan; Jang, S. H. (2015). Inter-organizational knowledge transfer through corporate venture capital investment. Management Decision, 53(7). https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/MRR-09-2015-0216

Lis, A., & Sudolska, A. (2015). Absorptive capacity and its role for the company growth and competitive advantage: The case of Frauenthal Automotive Toruń Company. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 11(4), 63–91. https://doi.org/10.7341/20151143

Liu, X., Wright, M., Filatotchev, I., Dai, O., & Lu, J. (2010). Human mobility and international knowledge spillovers: Evidence from high-tech small and medium enterprises in an emerging market. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 4(4), 340–355. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.100

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. The Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172. https://doi.org/10.2307/258632

March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71

Marvel, M. (2012). Knowledge acquisition asymmetries and innovation radicalness. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(3), 447–468.

McAdam, M., McAdam, R., Galbraith, B., & Miller, K. (2010). An exploratory study of principal investigator roles in UK university proof-of-concept processes: An absorptive capacity perspective. R and D Management, 40(5), 455–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2010.00619.x

McAdam, R., McAdam, M., & Brown, V. (2009). Proof of concept processes in UK university technology transfer: An absorptive capacity perspective. R and D Management, 39(2), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2008.00549.x

McGrath, R. G. (2001). Exploratory learning, innovative capacity, and managerial oversight. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 118–131. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069340

McKelvie, A., Wiklund, J., & Brattström, A. (2018). Externally acquired or internally generated? Knowledge development and perceived environmental dynamism in new venture innovation. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 42(1), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258717747056

Monferrer, D., Blesa, A., & Ripollés, M. (2015). Catching dynamic capabilities through market-oriented networks. European J. of International Management, 9(3), 384. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2015.069134

Moon, S. (2011). What determines the openness of a firm to external knowledge? Evidence from the Korean service sector. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 19(2), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/19761597.2011.630502

Mueller, P. (2006). Exploring the knowledge filter: How entrepreneurship and university-industry relationships drive economic growth. Research Policy, 35(10), 1499–1508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.09.023

Mueller, P. (2007). Exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities: The impact of entrepreneurship on growth. Small Business Economics, 28(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-006-9035-9

Newbert, S. L. (2005). New firm formation a dynamic capability perspective. Journal of Small Business Management 2005, 43(1), 55–77.

Newey, L. R., & Zahra, S. A. (2009). The evolving firm: How dynamic and operating capabilities interact to enable entrepreneurship. British Journal of Management, 20(SUPP. 1), S81–S100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00614.x

Nielsen, K. (2015). Human capital and new venture performance: The industry choice and performance of academic entrepreneurs. Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(3), 453–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-014-9345-z

Patterson, W., & Ambrosini, V. (2015). Configuring absorptive capacity as a key process for research intensive firms. Technovation, 36, 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2014.10.003

Patton, D. (2014). Realising potential: The impact of business incubation on the absorptive capacity of new technology-based firms. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 32(8), 897–917. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613482134

Perez, L., Whitelock, J., & Florin, J. (2013). Learning about customers: Managing B2B alliances between small technology startups and industry leaders. European Journal of Marketing, 47(3), 431–462. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561311297409

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Prashantham, S., & Young, S. (2011). Post-entry speed of international new ventures. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 35(2), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00360.x

Qian, H., & Acs, Z. J. (2013). An absorptive capacity theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9368-x

Rhee, J. H. (2008). International expansion strategies of Korean venture firms: Entry mode choice and performance. Asian Business & Management, 7(1), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.abm.9200246

Saemundsson, R. J., & Candi, M. (2017). Absorptive capacity and the identification of opportunities in new technology-based firms. Technovation, 64–65(June), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2017.06.001

Simsek, Z., & Heavey, C. (2011). The mediating role of knowledge-based capital for corporate entrepreneurship effects on performance: A study of small- to medium-sized firms. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 5(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.108

Sirén, C., Hakala, H., Wincent, J., & Grichnik, D. (2017). Breaking the routines: Entrepreneurial orientation, strategic learning, firm size, and age. Long Range Planning, 50(2), 145–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2016.09.005

Spencer, A. S., & Kirchhoff, B. A. (2006). Schumpeter and new technology based firms: Towards a framework for how NTBFs cause creative destruction. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 2(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-006-8681-3

Sullivan, D. M., & Marvel, M. R. (2011). Knowledge acquisition, network reliance, and early-stage technology venture outcomes. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6), 1169–1193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00998.x

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

Teece, D. J. (2012a). Dynamic capabilities: Routines versus entrepreneurial action. Journal of Management Studies, 49(8), 1395–1401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01080.x

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-7088-3.50009-7

Tolstoy, D. (2009). Knowledge combination and knowledge creation in a foreign-market network. Journal of Small Business Management, 47(2), 202–220.

Un, C. A., & Montoro-Sanchez, A. (2011). R&D investment and entrepreneurial technological capabilities: Existing capabilities as determinants of new capabilities. International Journal of Technology Management, 54(1), 29–52. https://doi.org/10.5114/pg.2018.74563

van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Volberda, H. W., Foss, N. J., & Lyles, M. A. (2010). Absorbing the concept of absorptive capacity: How to realize its potential in the organization field. Organization Science, 21(4), 931–951. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0503

Wadhwa, A., & Hall, M. (2005). Knowledge creation through external venturing: Evidence from the telecommunication. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 819–835. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159800

Wales, W. J., Parida, V., & Patel, P. C. (2013). Too much of a good thing? Absorptive capacity, firm performance, and the moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 34(5), 622–633. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2026

Winkelbach, A., & Walter, A. (2015). Complex technological knowledge and value creation in science-to-industry technology transfer projects: The moderating effect of absorptive capacity. Industrial Marketing Management, 47, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.02.035

Witt, P. (2004). Entrepreneurs’ networks and the success of start-ups. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 16(5), 391–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/0898562042000188423

Yu, J., Gilbert, B. A., & Oviatt, B. M. (2011). Effects of alliances, time, and network cohesion on the initiation of foreign sales by new ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 32(4), 424–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.884

Zahra, S. A., Filatotchev, I., & Wright, M. (2009). How do threshold firms sustain corporate entrepreneurship? The role of boards and absorptive capacity. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(3), 248–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.09.001

Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 185–203. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2002.6587995

Zahra, S. A., & Hayton, J. C. (2008). The effect of international venturing on firm performance: The moderating influence of absorptive capacity. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(2), 195–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2007.01.001

Zahra, S. A., Sapienza, H. J., & Davidsson, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 917–955.

Zheng, Y., Liu, J., & George, G. (2010). The dynamic impact of innovative capability and inter-firm network on firm valuation: A longitudinal study of biotechnology start-ups. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(6), 593–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.02.001

Zuzul, T., & Tripsas, M. (2019). Start-up Inertia versus flexibility: The role of founder identity in a nascent industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839219843486

Appendix A. Coding process of the three clusters of research guidelines

Knowledge cluster

|

AUTHORS |

YEAR |

JOURNAL |

TYPE |

AIM OF RESEARCH |

RELEVANCE OF AC |

METHODOLOGY |

SAMPLE |

VARIABLES |

FINDINGS |

FUTURE RESEARCH AGENDA |

|

AUTHORS |

YEAR |

JOURNAL |

TYPE |

AIM OF RESEARCH |

RELEVANCE OF AC |

METHODOLOGY |

SAMPLE |

VARIABLES |

FINDINGS |

FUTURE RESEARCH AGENDA |

|

Mueller |

2006 |

RESEARCH POLICY |

Empirical article |

To understand the role of entrepreneurship and university-industry relations to acquire new knowledge to contribute to regional economic growth. |

To identify, capture, and exploit new knowledge. |

Cobb-Douglas production function. Panel data cross-sectional time series. |

West German region (institutions, universities, new ventures, and firms). |

Dependent: Knowledge related entrepreneurship (startups). University-industry relations (grants, spillovers, spinoffs) |

There is a positive relationship between a well-developed regional knowledge stock and regional economic performance. Regions with a higher level of entrepreneurship (especially in innovative industries) experience greater economic performance. Universities are a source of innovation. |

Research visibility of universities’ relevance to regional growth. Studies on public policy on innovation |

|

Zahra et al. |

2009 |

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS VENTURING |

Conceptual article |

How threshold companies (the intermediate stage between startup and established companies) develop new capabilities to improve performance. |

AC has two major functions: wealth creation and protection of shareholders’ interests. AC allows threshold companies to convert their knowledge into products, goods, and services that create wealth. |

Literature review |

_ |

_ |

To develop AC requires sustained investments in human resources, infrastructure, and research programs. Managerial accountability and AC can sometimes substitute for each other while being complementary. |

Follow-up with empirical research to validate the propositions proposed, incorporating measures of managers’ skills and environmental conditions. To examine the potential interactions between managerial accountability and absorptive capacity at different thresholds of firms’ evolution. |

|

De Clercq et al. |

2012 |

JOURNAL OF BUSINESS VENTURING |

Conceptual article |

To provide an evaluative overview and evaluation of published research on the roles of learning and knowledge in early new ventures internationalization. |

To capture new knowledge based on the preexisting knowledge in outcomes of early internationalization. |

Systematic Literature review |

48 relevant articles published between 1994 and 2010. |

_ |

Vicarious and congenital learning appear to play a central role in the internationalization process. Search is probably the leading KA type to enhance the post-entry performance. A new venture may be better able to absorb new foreign knowledge when it possesses an extensive knowledge base. |

Further studies regarding the individual learning level, center on explaining how a venture realizes learning advantages when internationalizing. |

|

Acs et al. |

2009 |

SMALL BUSINESS ECONOMICS |

Empirical article |

To develop a knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship to improve the microeconomic foundations of endogenous growth models. |

To acquire new knowledge. |

Longitudinal panel study. F-test, regression techniques, fixed effect panels. |

Startups data from World Bank across 1997-2004 from 19 countries. |

Dependent: Entrepreneurship |

Entrepreneurial activity does not involve only the creation and the management of opportunities, but also the exploitation of knowledge not capitalized by incumbent firms. |

Expand the explanation about where opportunities come from, how intra-temporal knowledge spillovers occur, and the dynamics of occupational choice leading to the new firm formation. |

|

Prashantham and Young |

2011 |

ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY AND PRACTICE |

Conceptual article |

To answer what explains differential internationalization speed among international new ventures, after their initial entry into international markets? |

AC allows knowledge creation and utilization that enhances a firm’s ability to gain and sustain a competitive advantage. |

Literature review |

_ |

_ |

The pace of internationalization varies according to new ventures’ capabilities in accumulating and utilizing knowledge through exploitative learning. Social capital could facilitate AC. |

Empirical research in order to validate the propositions suggested incorporating moderators and contingencies such as knowledge-intensity of the industry and firm, firm-specific factors, and home country effects. |

|

Bruneel et al. |

2010 |

STRATEGIC ENTREPRENEURSHIP JOURNAL |

Empirical article |

To address how firms can accumulate the knowledge and skills required for successful international expansion and how young firms may compensate for their lack of firm-level international experience by utilizing other sources of knowledge. |

Facilitates future learning of new and related knowledge. |

Survey, multiple regression, and sensitivity analyses. |

114 young, technology-based firms in Flanders, Belgium. |

Dependent: Extent of internationalization. |

The firm’s experience in a determined international market negatively moderates the effects of congenital and inter-organizational learning. The lower the startup’s experiential learning, the more the effects of the team’s prior international knowledge base and skills obtained by key partners. |

To conduct other empirical researches with larger samples in other regions and industries, and also longitudinal studies to analyze the dynamics of learning and internationalization. |

|

Fernhaber et al. |

2009 |

STRATEGIC ENTREPRENEURSHIP JOURNAL |

Empirical article |

To develop a knowledge-based model of internationalization to investigate the role of external sources of international knowledge |

AC is recognized as an organizational mechanism for integrating internal and external sources of knowledge. |

Longitudinal panel study. Interval regressions and correlations. |

206 U.S. high technology new ventures between 1996-2000. |

Dependent: New venture internationalization |

External sources are positively associated with a startup’s level of internationalization. The nature of external sources of international knowledge depended on the international knowledge of the new venture’s team. |

Additional tests using other samples, and comparing new and mature firms to analyze the differences. To include the international entry year as a control variable. And to examine how external sources of knowledge impact a new venture’s country location decision, taking into consideration country differences. |

|

Yu et al. |

2011 |

STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT JOURNAL |

Empirical article |

To examine the role of networks in accelerating new venture sales into foreign markets |

To help young ventures to learn new knowledge in foreign markets |

Longitudinal panel study. Cox proportional hazard models, regressions, and correlations. Kaplan-Meier analysis. |

Longitudinal dataset of 118 new ventures in the U.S (1990-2000). |

Dependent: Venture initiation of foreign sales. |

Knowledge derived from ventures’ technology and marketing alliances increases the likelihood that startups exploit opportunities in international markets. The probability of a startup initiating foreign sales may be altered by the technological and marketing relationships and by the time required for process knowledge and to exploit international opportunities |

New empirical studies considering other high-tech industries, environments, and characteristics. To study how a venture’s alliance network influences its degree and scope of internationalization through longitudinal analyses. |

|

Bingham, and Davis |

2012 |

ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL |

Conceptual article |