Received 3 October 2017; Revised 17 January 2018; Accepted 26 February 2018.

Katarzyna Grzesik, Ph.D., Wroclaw University of Economics, Komandorska 118/120, 53-345 Wrocław, Poland, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Katarzyna Piwowar-Sulej, Dr hab., Wroclaw University of Economics, Komandorska 118/120, 53-345 Wrocław, Poland, e-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Abstract

The aim of the article is to present the issue of project manager competencies and project leadership styles which occur in different types of project-oriented organizations, i.e., the strictly project-oriented organizations (implementing projects for external clients) and organizations that manage projects for internal purposes. The subject literature studies and empirical research results conducted in 100 enterprises were used to accomplish the above-defined goal. The authors discussed the specific nature of project-oriented work and the specificity of project team management. A literature review on project manager competencies and project leadership styles was conducted. Three important competencies were identified that differentiate project managers between those working in strictly project-oriented organizations and those working in organizations which perform project-based management for internal purposes, i.e., achievement orientation, sensitivity teamwork and cooperation. The analysis of applied and desired leadership styles indicated a preference by project team members for a democratic leadership style, in particular during the project implementation phase, in both types of project-oriented organizations.

Keywords: project manager, competencies, leadership, project success.

INTRODUCTION

A thesis can be put forward that nowadays the attention of practitioners and management theorists is focused on the increasing dynamics of organizations’ functioning. In the tactics of “market players” repetitive and routine activities gradually lose importance in favor of unique and complex ventures – i.e., projects. A project is “an endeavour in which human, financial, and material resources are organized in a novel way to undertake a unique scope of work, of a given specification, within the constraints of cost and time, so as to achieve beneficial change defined by the quantitative and qualitative objectives” (Turner, 1993).

There is a growing interest in problems related to project management, also in the developing Polish economy. After systemic changes (the transition from socialism to a free market economy) the activities of organizations ceased to be predictable. Polish entrepreneurs started to take advantage of project management to accomplish various business goals. It is not surprising that the organization of work, in the form of projects, allows for the introduction of objective, transparent and standardized rules. These rules are, in turn, the source of structured and consistent information, fundamental for making proper business decisions. It is believed that predominantly classical project management methods are used in Poland, i.e., the ones based on the waterfall approach (Janasz & Wiśniewska, 2014). Furthermore, research on project maturity of Polish companies indicates a lower degree of maturity than in the case of foreign companies (Spałek & Karbownik, 2014).

Project management is the domain of project managers. They are responsible for the final result of the carried out project and have to be active in the course of all stages of the project. The job of a project manager has been included in the list of professions and specialties developed by the Polish Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy since 2014.

The theoretical concepts and research results on the competences of project managers can be found in the subject literature. The authors, discussing the analyzed problems, focus primarily on the specific types of projects or industries (Dvir et al., 2006; Müller & Turner, 2010; Dias et al., 2014). Project managers can manage various types of projects (construction, IT, organizational, etc.), which can influence the requirements regarding their knowledge and skills. They can also work in the strictly project-oriented organizations, i.e., those who implement projects ordered by an external customer (projects represent their core business) or organizations focused on repetitive activities, which manage projects for internal purposes. Based on literature studies, it was found that the problem of differences in the competencies of project managers, working in the aforementioned types of organizations, has not been studied as yet.

The publications on project management also analyze the impact of leadership style on project implementation, as well as offering tips on how to choose the right style for project team management (Müller & Turner, 2007). However, previous studies on project leadership styles have been conducted abroad. It was considered interesting to recognize and compare with the output of the management sciences, which styles of project team management are considered desirable in enterprises based in Poland.

On this basis, the purpose of the article was defined as the presentation of project manager competencies and project leadership styles which occur in different types of project-oriented organizations, i.e., the strictly project-oriented organizations (implementing projects for external clients) and organizations that manage projects for internal purposes. The following research questions have been posed:

Q1: What competency discrepancies occur between project managers working in the strictly project-oriented organizations (implementing projects for external clients) and organizations that manage projects for internal purposes?

Q2: What are the differences in the types of studied organizations in relation to the assessment of competencies regarding impacts on project manager effectiveness?

Q3: Do the applied and desired styles of project team management in the particular project phases meet the concept of Turner and Müller?

Subject-matter literature studies and empirical research results, carried out in the years 2014-2015 in 100 project-oriented organizations, were used to accomplish the above-defined goal. The intermediate stages along the set goal realization consisted of discussing the specific nature of project-oriented work and the specificity of project team management. A literature review on project manager competencies and project leadership styles was also conducted. Next, the methodology of empirical studies (in the context of a holistic research project and the content of this article) and their effects were discussed along with the resulting conclusions.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The specificity of work in a project and project team management

Project implementation involves three types of activities: operational (basic) activities, supporting (auxiliary) activities and managerial (directing) activities. The first type of activities, i.e., operational ones consist of transforming project input data into an expected result. These activities are directly related to the development of the project subject. They involve operational project-oriented activities consisting of preparing the description of the project subject (usually in the form of project documentation) and executive activities focused on material realization of the project subject. The second type of activities, i.e., the supportive ones serve as a backup for operational and managerial actions by creating adequate conditions for their efficient and effective implementation. They cover, e.g., the legal type of project execution support. The third type of activities refers to managerial tasks consisting of harmonizing operational and supporting activities. The latter is strictly connected with project team management. This team type is characterized by the following main features:

- it functions in a periodic mode;

- it can have a simple or a complex hierarchical structure;

- it is a sub-structure developed and based on the framework organizational structure of an enterprise.

It is worth mentioning that there are two dimensions of each project team functioning: the task dimension and the social dimension. The first one is related to the activities performed by the project team consisting of carrying out the project through its life cycle. The second one, in turn, involves developing substantive, interpersonal psychological and social relationships in a team. The task and social dimensions of a project team are interrelated. A change in one produces a change in the other. As Fujishin (2007) says, we do not really understand the subtle relationships between these dimensions, but we can be certain they do influence each other.

Even though projects can be implemented in a line unit by specialists representing one field of knowledge (e.g., the organization of an advertising campaign by a marketing team, where the department head is also the project manager), however, the interdisciplinarity requirement of contractors is more frequent in the definition of a project team or a project itself. In the functional structure, projects can be implemented by setting up a dedicated interdisciplinary project team. Such a team consists of line unit workers, delegated to work in the project on a temporary basis, or for the entire period of its implementation (full-time or part-time). The project manager is usually the line manager of this unit which takes the largest part in the project execution. In turn, the dominant type of organizational structure – according to Ansell (1993) – is the matrix structure.

Given the above, Table 1 shows the differences between work in interdisciplinary project teams and work in fixed enterprise structures (line unit). The information presented in the table identifies challenges faced by the project manager.

A project team is primarily a much more diverse team in terms of employees’ characteristics (specialization, terminology, work culture). This requires developing, for each individual project, the rules regarding the way of team work, the decision-making process, resolving conflicts, reporting on work progress and methods for making current administrative decisions (Wysocki, 2014).

Table 1. Differences between work in projects and work in a permanent, specialized unit in a given area of an organization

|

Comparative criterion |

Characteristics of work in projects |

Characteristics of work in a permanent unit of an organization |

|

Team type |

Interdisciplinary/heterogeneous |

Homogenous |

|

Team composition |

May vary in the course of project implementation |

Relatively stable – depending on an organization’s development needs or natural fluctuation |

|

Period of work execution |

Depends on project length or project stage |

Depending on the type of agreement and needs of an organization |

|

Overriding goal of work |

Introducing a change |

Efficient execution of certain activities |

|

Hierarchy |

Variable |

Fixed |

|

Risk/uncertainty level |

Higher |

Lower |

|

Variability of performed activities |

May be high – related to changes in project parameters |

Low – possibly related to the rotation in positions or permanent change of a position |

|

Direction of employee’s development |

Multitasking |

Specialization |

|

Performed roles |

May vary in various projects |

Relatively permanent – role change is associated with changing the position in the structure |

|

The required competencies easy to define |

Low |

High |

|

Knowledge management process easy to carry out |

Low |

High |

Source: authors’ compilation based on Piwowar-Sulej (2016) and Tyssen, Wald and Spieth (2014).

Depending on the complexity of the expected project outcomes the adequate project teams will vary in sizes. Both long-term, the so-called permanent enterprise staff, and the temporarily involved employees (e.g., within the framework of employee leasing) can take part in a project. The larger the team and the more diversified employment forms, the more difficult it is to find out about and to reconcile the expectations of its individual members.

In the project-oriented organization, an employee often plays a dual role: a line unit specialist and a project team member. He/she can also participate in several projects in parallel. Thus the problem of multiple subordination of a project team member occurs, as well as the related difference of interests between superiors (competing for employee’s competencies and time). This may result in difficulties with an employee’s work time organization and his/her efficiency in projects and in regular daily duties.

In the case of projects, it is difficult to develop a permanent list of activities and competencies required of team members. Projects represent a unique and one-off activity, which also makes it difficult to manage knowledge in such circumstances (accumulate it, apply it in subsequent projects - with different staff composition).

According to the opinion expressed by Melcher and Kayser (1970), leadership of a project group is difficult. A project manager is faced with two sets of problems. First, there is the problem of building a team that is directly under his control. Second, he must obtain the cooperation from other departments outside his authority. They are held responsible for the project but often with little or no formal authority over groups that provide essential information and services. The above-presented project work features and project management implications require from a project manager a set of specific competencies.

The competencies of a project manager

The competencies of a project manager constitute one of the success factors, as emphasized by e.g. Kendra and Taplin (2004), Cheng and Dainty (2005), Müller and Turner (2010), Madter, Bower and Aritua (2012), Gallagher, Mazur and Ashkanasy (2015), Maqbool, Sudong, Manzoor and Rashid (2017). The competencies of a project manager result directly from the performed functions and roles, as well as the implementation of tasks (Pettersen, 1991; Cobb, 2012; Anantatmula, 2010).

Competencies can be divided into different categories. The most common one is the basic division of competencies, taking into account hard competencies (referred to as technical, professional, vocational, substantive, functional), soft competencies (interpersonal, behavioral, social) and also conceptual (strategic) competencies. Hard competencies refer to skills in using the tools typical for a specific profession. They are needed to solve technical problems, to make decisions in specialized areas and also to train others. In turn, social competencies are based on the ability to cooperate with other people, to understand their needs and aspirations and to motivate them. Personality traits are the basis for developing such competencies. Conceptual competencies serve as a clamp binding the aforementioned two types of competencies. They represent the ability to coordinate and integrate all interests and directions of the carried out activities (Stoner & Wankel, 1986). In the past, the competencies deemed most important for effective project managers were of a more technical nature. However, it is now widely recognized that a mix of technical and people-oriented competencies are important for project managers success (Krahn & Hartman, 2004). What is more, the technical side of project management is well defined, so now attention is directed to the “soft” side, chiefly interpersonal competencies (Winter & Checkland, 2003; Dulaimi, 2005; Leybourne, 2007).

The detailed competencies of a project manager were the subject of research conducted by various researchers in different countries. For example, the research conducted by Geoghegan and Dulewicz (2008) points to 10 competencies (dimensions of leadership) which are critical for project success. Five of them are included in the group of so-called managerial competencies, four - in social competencies, and only one in intellectual competencies. Such competencies as resource management, delegating tasks, powers and entitlements (empowering), personnel development and motivation were listed among the most important ones for project success.

In another study, Gehring (2007) attempted to systematize the detailed competencies of a project manager. He distinguished the common competencies present on the lists of other authors investigating the analyzed subject matter and attributed to individual competencies the supporting personality types in line with Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator. It allowed the types of personalities supporting project realization through its consecutive phases to be identified. In turn, Dvir, Sadeh and Malch-Pines (2006) pointed out that project managers are more interested in participating in endeavors that match their personality. Some prefer to participate in imitation projects, whereas others prefer high-tech projects characterized by a high degree of uncertainty. It allows one to conclude that the personality traits of a project manager make him/her more or less competent for a particular project type, which has a direct impact on the success of a project. Hossein, Bakhsheshi and Rashidi Nejad (2011) identified which characteristics of a project manager are desirable depending on project types. The aforementioned authors also identified which characteristics of a project manager have the biggest impact on meeting the requirements related to, for example, time, cost, and quality of the project final outcome.

The most and the least, desirable personality traits of a project manager in certain types of projects are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Project type vs. desirable and undesirable personality traits of project managers

|

Project type |

Most desirable personality traits |

Least desirable personality traits |

|

Urgent |

integrity, meticulousness, intelligence |

self-control, emotional impulsiveness, impartiality, fairness |

|

Complex |

integrity, meticulousness, creativity |

impartiality, fairness, emotional impulse, enthusiasm, curiosity |

|

Innovative |

integrity, creativity, intelligence |

emotional impulsiveness, impartiality, fairness, self-control |

|

Standard |

integrity, persistence, meticulousness |

emotional impulsiveness, impartiality, fairness, enthusiasm, curiosity |

Source: Hossein, Bakhsheshi and Rashidi Nejad (2011).

Research on the competencies of a project manager, required for the implementation of different project types, was also carried out by Dias, Tereso, Braga and Fernandes (2014). The study applied a quantitative research approach for identifying key project managers’ competencies for different types of projects. The 46 competencies (technical, behavioral and contextual) provided by the IPMA (International Project Management Association) were surveyed through an online questionnaire. Three dimensions to distinguish project types were used: application area, innovation and complexity. The results showed that 13 key competencies (20%) were common to the majority of the projects. Most of these are behavioral competencies, such as ethics, reliability, engagement, openness, and leadership. A clear correlation was also observed between technical competencies and project complexity. Analysing projects with high complexity and, comparatively, with the other complexity levels, two technical competencies stand out: risk and opportunity, and team work.

Müller and Turner (2010) examined the leadership competency profiles of successful project managers in different types of projects. In order to develop leadership profiles of successful project managers in different types of projects, they adopted the assessment tool, the Leadership Development Questionnaire (LDQ), which has frequently been used in recent studies on leadership in project management. Four hundred responses to the Leadership Development Questionnaire (LDQ) were used to profile the intellectual, managerial and emotional competencies of project managers in successful projects. Differences by project type were accounted for through the categorization of projects by their application type (engineering & construction, information & telecommunication technology, organizational change), complexity, importance and contract type. This study used a worldwide, web-based questionnaire to identify the leadership competency profiles of successful project managers in projects of a different type. By focusing on the leadership profiles of successful managers only, Müller and Turner identified differences in the strength and presence of leadership competencies of managers in different types of projects. The results support the hypothesis that project manager leadership competency profiles differ in some project types in order to be successful. Results indicate high expressions of one IQ sub-dimension (i.e., critical thinking) and three EQ sub-dimensions (i.e., influence, motivation and conscientiousness) in successful managers in all types of projects. Expressions of other sub-dimensions differ by project type. The results support the previous research, which identified different profiles of leadership competence in organizational change projects of different complexity. The present study extends these findings to engineering & construction, information & telecommunication technology projects.

The above-mentioned tool Leadership Development Questionnaire (LDQ), which is used in studies on leadership in project management, was developed by Dulewicz and Higgs (2005). These researchers did an extensive review of existing theories and identified 15 leadership dimensions, which they then clustered under three competencies of intellectual, emotional and managerial (see Table 3). Using these 15 dimensions they identified three leadership profiles for organizational change projects, which they call goal-oriented, involving, and engaging; and which are appropriate depending on the level of change to be achieved within an organization. Engaging is a style based on empowerment and involvement in highly transformational context. This leadership style is focused on producing radical change through engagement and commitment. Involving is a style for transitional organizations which face significant, but not necessarily radical, change in their business model or way of work. Goal oriented is a style focused on delivery of clearly understood results in a relatively stable context.

The organizations promoting the domain of project management and developing project management methodologies prepared detailed lists of project manager’s competencies. One of the project manager’s competency models, recognized among professionals, is the Project Management Competency Development Framework (PMCD Framework), developed by the Project Management Institute.

Table 3. Fifteen leadership competencies and three styles of leadership as suggested by Dulewicz and Higgs

|

Group |

Competency |

Goal -oriented |

Involving |

Engaging |

|

Intellectual (IQ) |

Critical analysis and judgment Vision and imagination Strategic perspective |

High High High |

Medium High Medium |

Medium Medium Medium |

|

Managerial (MQ) |

Engaging communication Managing resources Empowering Developing Achieving |

Medium High Low Medium High |

Medium Medium Medium Medium Medium |

High Low High High Medium |

|

Emotional (EQ) |

Self-awareness Emotional resilience Motivation Sensitivity Influence Intuitiveness Conscientiousness |

Medium High High Medium Medium Medium High |

High High High Medium High Medium High |

High High High High High High High |

Source: Dulewicz and Higgs (2003).

The PMCD Framework is a comprehensive text defining project management competencies and provides the baseline list of competencies required for project success (Gehring, 2007). The competencies in the PMCD Framework are organized into six units of competence representing groups of distinguishing competencies (see table 4). Within each unit, the competencies relating to similar action or behavior are grouped to form the competency cluster.

Project team leadership style

The style of managing people refers to the relationship between superiors and subordinates. It is based on explicit or implicit influence exerted through management behaviors realized in the played organizational role. Based on individual experience, a supervisor develops patterns of his/her own desirable behavior and the desirable behavior of his/her subordinates. The patterns of a supervisor’s own behavior are related to the manner of executing managerial functions and powers, the set of accepted and applied methods and techniques used in managing people, as well as the manner of performing the organizational role. Three classical styles (Coghlan & Brannick, 2003) are the basis for describing and classifying different types of leadership styles, i.e., autocratic style, democratic style and laissez-faire style.

One of the critical factors of project success is the leadership style (Belout & Gauvreau, 2004; Turner & Müller, 2005; Feger & Thomas, 2012).

Table 4. Project manager competencies identified by the Project Management Institute

|

Unit of competence |

Competency cluster |

|

Achievement and Action |

Achievement orientation Concern for order, quality, and accuracy Initiative Information seeking |

|

Helping and Human Service |

Customer service orientation Interpersonal understanding |

|

Impact and Influence |

Impact and influence Organizational awareness Relationship building |

|

Managerial |

Teamwork and cooperation Developing others Team leadership Directiveness: Assertiveness and use of positional power |

|

Cognitive |

Analytical thinking Conceptual thinking |

|

Personal Effectiveness |

Self-control Self-confidence Flexibility Organizational commitment |

Source: Project Management Institute (2002).

Research on relationships between leadership style and project success suggested that successful project managers need to employ flexibility in their leadership style. Flexibility allows them to adjust and to apply different leadership styles that will suit changes in situations or circumstances (Prabhakar, 2005; Müller & Turner, 2007). Choosing the right leadership style can turn out to be crucial for the project outcome. The decision on which style to use in a given situation depends, to a great extent, on the intuition of a project manager and his/her ability to assess the situation correctly, as well as on his/her personal predispositions, i.e., which style suits him/her best (Frame, 2003). Apart from personal factors, the choice of leadership style is also influenced by task-oriented and organizational factors (see Table 5).

It should also be emphasized that one style of management neither can nor should be used in the course of project implementation. Each project implementation phase is related to the specific tasks, so the manager’s approach should depend on the actual circumstances at a given moment. Turner and Müller assigned management styles to project lifecycle phases and also to the structure type of the project team and the specificity of the team (see Table 6).

Table 5. Factors influencing project leadership style

|

Task factors |

Personal factors |

Organizational factors |

|

tasks are limited in time, relatively well-defined and executed under time pressure tasks are extensive, often very complex and poorly structured tasks are characterized by a high level of innovation and pose a high risk for an enterprise |

project implementation requires the cooperation of experts from various specialties the requirements regarding the competencies of a manager are diverse depending on the institutional form of project implementation higher than average requirements regarding communication and cooperation skills, resistance to stress and variability of roles are expected from project participants |

diverse resources being at the disposal of different organizational units in an enterprise are taken advantage of within the framework of projects a project is characterized by instability of operation project implementation frequently imposes subordination at work project implementation is divided into phases and different phases are associated with various organizational problems employees’ motivation problems represent the significant component of project implementation |

Source: authors’ compilation based on Trocki, Grucza and Ogonek (2003).

Table 6. Leadership styles vs. project phases and types of project teams

|

Leadership style |

Project lifecycle phase |

Project team structure type |

Team specificity |

|

Laissez-faire |

Commencement |

Collective |

Experts sharing responsibility |

|

Democratic |

Planning |

Matrix |

Many specialists are involved in several tasks |

|

Autocratic |

Implementation |

Task-oriented |

An individual is involved in the implementation of one specific type |

|

Bureaucratic |

Completion |

Surgical |

Joint work on a single task |

Source: authors’ compilation based on Turner and Müller (2005).

Cunningham, Salomone and Wielgus (2015) looked at six popular project management leadership styles across three industries to discover if there is commonality in each industry as well as if the preferred methodology differs from industry to industry. The researched leadership styles were coaching, strategic, laissez-faire, bureaucratic, autocratic, and democratic. The three industries surveyed were healthcare, finance, and pharmaceuticals. Data from the survey showed that all three industries identify best with strategic and democratic leadership styles. The healthcare industry preferred strategic and coaching best, the finance industry preferred strategic and democratic, and pharmaceuticals preferred strategic, coaching, and democratic styles almost equally. Bureaucratic leadership was proven to be the least preferred style across all three industries.

Much of the current work on leadership, in specialist project management literature, stresses the importance of the so-called ‘transformational leadership. The relationship between the project team member and the project manager as a leader is likely to be different from the traditional leader-follower relationship in a functional hierarchy. Although the project manager is responsible for the day-to-day work of the team members, often for long periods of time, he or she often has an unclear role to play in the overall development, career plans and longer-term goals of the project team member. Project-based organizing, in particular, may undermine strong identification between leaders and followers, which is the core aspect of transformational leadership. The identification and trust-building processes involved in transformational leadership may thus be less likely to occur or less easy to achieve in such temporary, shifting relationships (Keegan & Den Hartog, 2004).

Yanga, Huang and Wu (2011) investigated the associations between the project manager’s leadership style and teamwork and the impact of teamwork on project performance. These analyses showed that the increase in leadership levels might enhance relationships among team members. More specifically, the results indicate that the project managers who adopt transactional and transformational leadership may improve team communication, team collaboration and team cohesiveness. In investigating the relationship between teamwork and project performance, teamwork is positively related to project performance. The findings suggest that project success in terms of schedule performance, cost performance, quality performance, and stakeholder satisfaction can be achieved with stronger team communication and collaboration, as well as greater team cohesiveness.

Martin and Edwards (2016) explored leadership style at different managerial levels. The democratic and transformational styles of leadership were the most efficient in achieving project success. An analysis of variance revealed there is no significant relationship between project success and leadership style, but there exists a strong association between management level and leadership style and a significant relationship between management level and project success. This suggests there is a maturity in leadership style as management level progresses, as a person should become more effective in guaranteeing project success based on how far they have progressed in the management structure of their organization.

Nauman (2012) has examined the relationship between social intelligence with leadership behavior in less virtual and more virtual teams. The findings of current research highlight the importance of social intelligence and concern for task in more virtual projects as compared to less virtual projects. The findings suggest that social intelligence does matter in the management of IT projects both less and more virtual in nature and it is imperative for more virtual projects. The results show that social awareness and relationship management are positively related to concern for task and concern for people and are found to be higher in more virtual than less virtual project team members.

RESEARCH METHODS

The research results presented in this paper are part of a holistic research project, carried out in the years 2014-2015, dedicated to managing people in project-oriented organizations. The research was “embedded” in an interpretative paradigm, which predominantly emphasizes pragmatism and coherence (for more see Smith, 1983).

In the holistic research project, pilot studies were based on focus-group interviews carried out with people holding different positions (i.e., project managers, HR staff, project work executors). Such interviews are used, e.g., as an auxiliary tool for obtaining basic data needed to define the research problems and to construct a tool in the form of a questionnaire (for more see Merton, 1987). The interviews were organized with three mini-focus-groups. In turn, in the course of proper research, the structured interview method (PAPI - Paper and Pencil Interview) was used, conducted with the above-mentioned groups of respondents (3 respondents from each organization: 1 HR specialist, one project manager and one project work executor). The questions in questionnaires were divided according to thematic blocks. Both closed and open questions were used.

This article – taking into account its purpose (i.e., identification of the required and frequently used competencies and project leadership styles) – presents the results of structured interviews with project work executors, who were employed in the surveyed enterprises.

A medium or large enterprise was the basic sample unit, in which:

- Projects are implemented.

- Project manager position or function is introduced.

- There is an organizational structure in which two dimensions coexist - hierarchical (line units) and projects (interdisciplinary project teams).

- Methodical approach to project management is used.

The sample units were divided into two types characterized in Table 7.

Table 7. The characteristics of enterprise types covered by the research

|

Type name |

Enterprise characteristics |

Examples of industries |

|

A |

Strictly project-oriented organizations, in which projects are implemented mainly for external needs (projects constitute the core business here) |

Construction, contracted manufacturing, architecture, advertising, consulting, IT, research and development |

|

B |

Organizations in which projects are implemented primarily for internal needs |

Mass production, transport, telecommunications, trade and commerce, healthcare, finance |

The research included 100 organizations located in Poland. The research sample was balanced, i.e., covered an equal number of companies of all types (50 strictly project-oriented ones where projects constitute their core business and 50 carrying out mainly repetitive activities but managed by projects for their internal needs). When designing the research sample, it was taken into account that, while there is a certain number of first type enterprises in the market, it is difficult to identify the other organizations in which project-oriented management takes place. It is difficult to determine how big the general population is, which is why the number of organizations of these two types was balanced in the research sample. Also, within each group (A and B) a layered selection according to the examples of industries listed in table 7 (maintaining the proportions indicated in the classifications of The Main Statistical Office) was used. In the process of data collection and statistical analysis, cooperation with the Center for Research and Expertise of the University of Economics in Katowice and the Wrocław University of Science and Technology was initiated.

The identification of project managers’ competencies (Q1) was based on the PMCD Framework and leadership dimensions identified by Dulewicz and Higgs presented above. In the PMCD model there are 19 competences and in the Dulewicz and Higgs model, there are 15 competences. Because certain competences (12 competences) mentioned in the indicated models are repeated, a list covering 22 competences was adopted for research.

The respondents were asked whether, and to what extent, the project managers they cooperated with were characterized by the competencies indicated in the listed theoretical concepts. They could answer based on a five-point scale, where 1 indicated that the managers definitely do not have the particular competency, 2 - rather do not have it, 3 - I cannot say, 4 - they rather have it, and 5 - they definitely have it. Logistic regression was mainly used to determine whether there is a difference in managerial competencies between type A and B organizations.

The respondents were also asked to highlight three key competencies (Q2) which determine the effectiveness of project managers. The previously developed list of 22 competencies based on PMCD concepts and 15 leadership dimensions was referred to.

The research (Q3) also used the aforementioned concept by Turner and Mueller, presenting the desired leadership styles in subsequent phases of the project. The following categorization of leadership styles was used to analyze a particular leadership style:

- laissez-faire leadership style - team members identify themselves with the specific options/variants of activities and make decisions, the methods of functioning/working in a team are flexible;

- democratic leadership style - the manager engages/involves the team members in identifying specific options/variants of activities and makes decisions him/herself, the methods of functioning/working in a team are flexible;

- autocratic leadership style - the manager him/herself determines the possible methods/variants of activities and makes decisions him/herself, the methods of functioning/working in a team are flexible;

- bureaucratic leadership style - the manager him/herself determines the possible methods/variants of activities and makes decisions him/herself, the methods of functioning/working in a team follow specific rules.

The respondents were also able to answer that they cannot clearly indicate which leadership style is the dominant one in practice and which, in their opinion, is the desired one. The results of conducted empirical research, assigned to the previously defined research questions (Q1-Q3), are discussed in the next part of the article.

RESULTS ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

The research on the competences (Q1 and Q2) conducted in two types of project-oriented organizations showed some differences regarding the project manager competences.

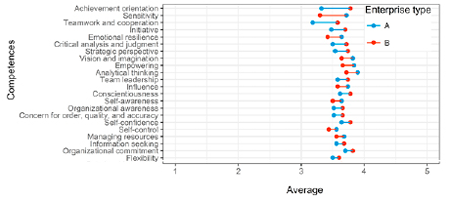

The variables for the model (Q1) were selected by comparing the differences between the mean values of manager competency assessments for the organizations of A and B type. The classified differences (higher regarding the absolute value that is higher or equal to 0.1) are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The differences in average project manager competency assessments by the type of organization

Further analysis covered these competencies for which the differences in assessments were higher than 0.2. This value was regarded as significant from a practical perspective. The variables (competences) meeting this criterion are as follows: achievement orientation, sensitivity, teamwork and cooperation, initiative, emotional resilience, critical analysis and judgment and also strategic perspective. The preliminary analysis based on the reverse elimination method combined with logistic regressions with one explanatory variable showed that three variables with the highest difference should be adopted for the model, i.e., achievement orientation (AO), sensitivity (S) and also teamwork and cooperation (TC). At this point, it is worth noticing that AO and TC competencies originate from the PMCD concept by PMI, whereas S concept comes from the concept of Dulewicz and Higgs. The form of the adopted statistical model is presented below:

Prob (organization type = b) = 1/(1+ exp(-Xß), where: Xß = a? + a1AO +a2S +a3TC

The initial assessment was to determine whether the suggested model was significantly different from the model with a constant only (i.e., there are no variables). Upon the test result based on the reliability function quotient (d.f.: 3, P-value: 3.6e-06) it should be observed that there is a statistically significant difference between the models - obviously in favor of the model with variables (low p-value < 0.05). Thus, at least some variables substantially explain the differences between the particular industries. In the next step, the focus was on the significance of each variable, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8. Parameters of the adopted statistical model

|

Competence |

Coef |

S.E. |

Wald Z |

p-value |

|

Intercept |

-3.071 |

1.74 |

-1.765 |

0.078 |

|

AO |

1.128 |

0.41 |

2.750 |

0.006 |

|

S |

-1.083 |

0.35 |

-3.091 |

0.002 |

|

TC |

0.844 |

0.33 |

2.557 |

0.011 |

Wald Z statistics and the corresponding p-values are lower than the adopted significance level (\alpha = 0.05 \). This suggests that the estimated coefficients are statistically significant. The statistical tests used so far allowed the assessment of whether there are relationships between the type of enterprise and other variables, and whether these relationships can be considered relevant. However, they do not explicitly answer the question about how useful the model is going to turn out to be in the classification process, i.e., whether the knowledge of competencies is sufficient to predict the type of industry represented by the manager. The predictive capacity of the model was additionally assessed on the basis of the so-called discriminatory indexes.

The estimated coefficients allow the relationships between B industry affiliation and the competences presented by managers to be interpreted. It turns out that the higher the assessment of AO competencies or TC competencies, the higher the probability that the project manager is working in a B-type organization. In turn, the higher the assessment of S competences, the higher the probability that the project manager is working in an A-type enterprise.

Sensitivity, which means awareness of, and taking account of, the needs and perceptions of others in arriving at decisions and proposing solutions to problems and challenges, is a part of emotional competencies in Dulewicz and Higgs dimensions. The specificity of project management creates the need for the project manager to present emotional intelligence and the related competencies. In the research focused on investigating relationships between the project manager’s competencies and the project success, Geoghegan and Dulewicz (2008) pointed to three competencies related to emotional dimensions, i.e., conscientiousness, self-awareness, and sensitivity as crucial for the project success. Also, in other studies, such emotional competencies as self-confidence and self-belief were presented as likely to play a significant part in the project manager’s ability to deliver a project successfully (Lee-Kelley & Leong Loong, 2003).

Thus, distinguishing S competence as distinctive for managers in A-type organizations may suggest the need for the project manager’s interaction with a more diverse group of project stakeholders than in the case of B-type organizations implementing projects for internal needs. Emotional competences mainly allow developing interpersonal relationships with the broadly approached project stakeholders. On the other hand, in the case of B-type organizations, the distinction of AO and TC competencies may indicate a focus on enterprise development, which is related to the implementation of internal projects in an enterprise.

There are also some differences in competencies which determine project manager effectiveness in A and B-types organizations. Competencies indicated by the highest number of respondents (more than 10 indications) in each of the identified types of organizations were adopted for the analysis. In A-type organizations the most frequently indicated competencies, which determine a project manager’s effectiveness are listed below:

- Development (D) - 36 indications – which is connected with impact and influence in which the intention is to teach or foster the development of one or several other people;

- Motivation (M) - 15 indications – which is connected with energy to achieve clear results and make an impact;

- Self-confidence (SC) - 12 indications – which means a person’s belief in one’s own capability to accomplish a task, and includes a person expressing confidence in dealing with increasingly challenging circumstances, in reaching decisions or forming opinions, and in handling failures constructively.

In B-type organizations – in the opinion of project work executors – the most important competencies, which decide about a project manager’s effectiveness, are as follows:

- Teamwork and cooperation (TC) – the number of indications: 39 – which is understood as a genuine intention to work cooperatively with others, to be part of a team, to work together as opposed to working separately or competitively;

- Vision and imagination (VI) – which means a clear vision of the future and the impact of changes on implementation issues and business realities, and Development (D) - the number of this competence indications: 18.

Regarding the responses given to Q1 and Q2, it should be observed that TC competence, considered important for identifying discrepancies between project managers in strictly project-oriented organizations and managers in organizations that manage projects for internal needs, was selected as the key competence determining a manager’s effectiveness in B-type organizations. Having analyzed the most important competencies determining the effectiveness of managers in the organizations implementing projects for their own needs, i.e., TC, VI (vision and imagination) and D (development), it can be concluded that these competences are focused on the internal relationships in an organization.

The analysis of the empirical research results conducted in 100 enterprises project-oriented organizations indicated that, in the surveyed organizations, applied and desired leadership styles are not in accordance with the Turner and Mueller concept (Q3).

The so-called Adjusted Rand Index was applied to investigate compatibility between the model style of management within a given project phase (i.e., in accordance with the Turner and Mueller concept) and the styles indicated by the respondents as used or desired. This index is often applied to assess the degree of classification correctness. It takes the highest value equal to 1 if there is full compatibility between the model and the styles in the questions about the actually applied and the desired leadership styles. The value equal to 0 or less means that there is no compliance.

Table 9 presents how many organizations use the defined (considered as dominant) style of project team management in relation to the styles indicated as model ones in the Turner and Mueller concept.

Table 9. The discrepancies between model and applied leadership styles

|

Model style Applied style |

Autocratic (project implementation phase) |

Bureaucratic (project completion phase) |

Democratic (project planning phase) |

Laissez-faire (project initiation phase) |

|

Autocratic |

25 |

40 |

28 |

41 |

|

Bureaucratic |

19 |

25 |

7 |

15 |

|

Democratic |

47 |

29 |

50 |

33 |

|

Laissez-faire |

5 |

3 |

8 |

7 |

The value of Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) for the question about the leadership style used by managers was 0.017, which is the value proving the absence of compliance with the model concept. Table 10 presents how many organizations prefer each type of leadership style in relation to the styles indicated as model ones in the Turner and Mueller concept.

It is worth mentioning once more, that the respondents could answer that they cannot clearly indicate which leadership style is the dominating one in practice and which, in their opinion, is the desired one. This is the reason, why there are some differences in total numbers presented in table 9 and 10.

This result is partly different from the actual situation in Polish organizations, as the research conducted in Polish enterprises suggests that the majority of entrepreneurs prefer an autocratic leadership style (decisions are made without the involvement of employees).

Table 10. Discrepancies between model and desired leadership styles by project work executors

|

Model style Applied style |

Autocratic (project implementation phase) |

Bureaucratic (project completion phase) |

Democratic (project planning phase) |

Laissez-faire (project initiation phase) |

|

Autocratic |

20 |

26 |

17 |

3 |

|

Bureaucratic |

10 |

16 |

6 |

5 |

|

Democratic |

61 |

47 |

68 |

33 |

|

Laissez-faire |

8 |

9 |

9 |

9 |

This may be due to the relatively widespread principle of limited confidence in employees, which results from the conviction that it is better to exercise control over an employee. However, one can also see the emerging tendency towards moving from an autocratic to a democratic leadership style (Mączyński, 2010).

On the other hand, while analysing the applied project team leadership styles, in the particular project implementation phases, two of the four examined leadership styles are the dominating ones, i.e. the autocratic style, which was most often indicated at the initial and final phase of the project and the democratic style most often pointed to in the planning and implementation phases of the project.

CONCLUSION

Within the group of the analyzed enterprises, the following three important competencies were identified, which differentiate project managers between those working in strictly project-oriented organizations and the organizations which perform project-based management for internal purposes: achievement orientation (AO), sensitivity (S) and also teamwork and cooperation (TC). Managerial competencies decide primarily about the effectiveness of project manager activities. The analysis of applied and desired leadership styles indicated project team members’ preference for a democratic leadership style in the particular project implementation phases. In turn, in terms of the actually applied leadership styles, the combination of democratic and autocratic styles prevails, however, the autocratic style is the dominating one in the initial and completion project phase, whereas the democratic style in the planning and implementation phase.

The empirical research results presented in this article are primarily of a cognitive nature. The main research limitation is the small research sample size, which does not allow the results to be generalized. In order to present the determinants influencing the picture obtained from the discussed competencies and leadership styles, it seems founded to carry out further exploratory research. The authors hope that the publication will remain an inspiration for further empirical research including a comparison between different countries.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from the National Science Centre in Poland (DEC--2013/09/D/HS4/00566).

References

Anantatmula, V.S. (2010). Project manager leadership role in improving project performance. Engineering Management Journal, 22(1), 13-22.

Ansell, T. (1993). Managing for Quality in the Financial Services Industry. London, England: Chapman&Hall.

Belout, A., & Gauvreau, C. (2004). Factors affecting project success: The impact of human resource management. International Journal of Project Management, 22(1), 1-12.

Cheng, M.I. & Dainty, A.R.J. (2005). What makes a good project manager?. Human Resources Management Journal, 15(1), 25-37.

Cobb, A.T. (2012). Leading Project Team. The Basics of Project Management and Team Leadership (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Coghlan, D., & Brannick, T. (2003). Kurt Lewin: The “practical theorist” for the 21st century. Irish Journal of Management, 24(2), 31.

Cunningham, J., Salomone, J., & Wielgus, N. (2015). Project management leadership style: A team member perspective. International Journal of Global Business, 8(2), 37-54.

Dias, M., Tereso, A., Braga, A.C., & Fernandes, A.G. (2014). The key project managers’ competencies for different types of projects, In Á. Rocha, A. Correia, F. Tan & K. Stroetmann (Eds.), New Perspectives in Information Systems and Technologies (Vol. 1, pp. 359-368). New York, NY: Springer International Publishing.

Dulaimi, M.F. (2005). The influence of academic education and formal training on the project manager’s behavior. Journal of Construction Research, 6(1), 179-193.

Dulewicz, V., & Higgs, M.J. (2005). Assessing leadership styles and organisational context. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(2), 105-123.

Dvir, D., Sadeh, A., & Malch-Pines, A. (2006). Projects and project managers: The relationship between project manager’s personality, project types and project success. Project Management Journal, 37(5), 36-48.

Feger, A. L., & Thomas, G.A. (2012). A framework of exploring the relationship between project manager leadership style and project success. The International Journal of Management, 1(1), 1–19.

Frame, J.D. (2003). Managing Projects in Organizations: How to Make the Best Use of Time, Techniques, and People (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Fujishin, R. (2007). Creating effective Groups. The art of small group communication (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc.

Gallagher, E.C., Mazur, A.K., & Ashkanasy, N.M. (2015). Rallying the troops or beating the horses? How project-related demands can lead to either high-performance or abusive supervision. Project Management Journal, 46(3), 10–24.

Gehring, D.R. (2007). Applying traits theory of leadership to project management. Project Management Journal, 38(1), 44-54.

Geoghegan, L., & Dulewicz V. (2008). Do project managers’ leadership competencies contribute to project success? Project Management Journal, 39(4), 58-67.

Hossein, A., Bakhsheshi, F., & Rashidi Nejad, S. (2011). Impact of project managers’ personalities on project success in four types of project. In 2nd International Conference on Construction and Project Management IPEDR (Vol. 15, pp. 181-186). Singapore: IACSIT Press.

Janasz, K., & Wiśniewska, J. (2014). Zarządzanie Projektami w Organizacji [Project management in an organization]. Warszawa, Poland: Difin.

Keegan, A.E., & Den Hartog, D.N. (2004). Transformational leadership in a project-based environment: a comparative study of the leadership styles of project managers and line managers. International Journal of Project Management, 22(8), 609–617.

Kendra, K., & Taplin, L.J. (2004). Project success: A cultural framework. Project Management Journal, 35(1), 30-45.

Krahn, J., & Hartman, F.T. (2004). Important leadership competencies for project managers: The fit between competencies and project characteristics. Paper presented at PMI® Research Conference: Innovations, London, England. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Lee-Kelley, L., & Leong Loong, K. (2003). Turner’s five functions of project-based management and situational leadership in IT services project. International Journal of Project Management, 21(8), 583-591.

Leybourne, S. (2007). The changing bias of project management research: A consideration of the literature and an application of extant theory. Project Management Journal, 38(1), 61–73.

Martin, H., & Edwards, K. (2016). The interaction between leadership styles and management level, and their impact on project success, In H.H. Laun, F.E. Tang, C.K. Ng & A. Singh (Eds.), Integrated Solutions for Infrastructure Development. Fargo, ND: ISEC Press.

Madter, N., Bower, D.A., & Artua, B. (2012). Projects and personalities: A framework for individualising project management career development in the construction industry. International Journal of Project Management, 30(3), 273-281.

Maqbool, R., Sudong, Y., Manzoor, N., & Rashid, Y. (2017). The impact of emotional intelligence, project managers’ competencies, and transformational leadership on project success: An empirical perspective. Project Management Journal, 48(3), 58–75.

Mączyński, J. (2010). Dostosowanie stylu zarządzania polskich menedżerów do standardów Unii Europejskiej poprzez „Trening Partycypacji Decyzyjnej” [Adjustment of management styles of Polish managers to European Union standards through “decision participation training”]. Edukacja Dorosłych [Adult Education], 1(62), 159-174.

Melcher, A.J., & Kayser, T.A. (1970). Leadership without formal authority. The project department. California Management Review, 13(2), 57-64.

Müller, R., & Turner, J.R. (2007). Matching the project manager’s leadership style to project type. International Journal of Project Management, 25(1), 21-32.

Müller, R., & Turner, R. (2010). Leadership competency profiles of successful project managers. International Journal of Project Management, 28(5), 437–448.

Nauman, S. (2012). Patterns of social intelligence and leadership style for effective virtual project management. International Journal of Information Technology Project Management, 3(1), 49-63.

Pettersen, N. (1991). What do we know about the effective project manager? International Journal of Project Management, 9(2), 99-104.

Piwowar-Sulej, K. (2016). Postawy wobec pracy w projektach oraz ich determinanty [Attitudes towards work in projects and their determinants]. Edukacja Ekonomistów i Menedżerów [Education of Economists and Managers], 1(39), 173-185.

Prabhakar, G.P. (2005). Switch leadership in projects: An empirical study reflecting the importance of transformational leadership on project success across twenty eight nations. Project Management Journal, 36(4), 53-60.

Project Management Institute, (2002). Project Manager Competency Development Framework. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Smith, J.K. (1983). Quantitative versus qualitative research: An attempt to clarify the issue. Educational Researcher, 12(3), 6-13.

Spałek, S., & Karbownik, A. (2014). Rekomendacje dla zwiększenia stopnia dojrzałości w zarządzaniu projektami w przedsiębiorstwach przemysłu maszynowego w Polsce. Przegląd Organizacji, 9, 8-12.

Stoner, J.A.F., & Wankel, Ch. (1986). Management (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Trocki, M., Grucza, B. & Ogonek, K. (2003). Zarządzanie Projektami [Project management], Warszawa: PWE.

Turner, J.R., & Müller, R. (2005). The project manager’s leadership style as a success factor on projects: A literature review. Project Management Journal, 36(2), 49-61.

Turner, J.R. (1993). The Handbook of Project-based Management – Improving the Processes for Achieving Strategic Objectives. London, England: McGraw-Hill.

Tyssen, A.K., Wald, A., & Spieth, P. (2014). The challenge of transactional and transformational leadership in projects. International Journal of Project Management, 32(3), 365-375.

Winter, M., & Checkland, P. (2003). Soft system: A fresh perspective for project management. Proceeding of ICE – Civil Engineering, 156(4), 187-192.

Wysocki, R.K. (2014). Effective Project Management: Traditional, Agile, Extreme (7th ed.). Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley & Sons.

Yanga, L., Huang, Ch., & Wu, K. (2011). The association among project manager’s leadership style, teamwork and project success, International Journal of Project Management, 29(3), 258–267.

Abstrakt

Celem artykułu jest przedstawienie kompetencji kierownika projektu oraz stylów kierowania projektem występujących w różnych typach organizacji zorientowanych na projekty, tj. organizacjach stricte projektowych (realizujących projekty dla klientów zewnętrznych) oraz organizacjach zarządzających projektami na potrzeby wewnętrzne. Do osiągnięcia powyższego celu wykorzystano studia literatury przedmiotu oraz badania empiryczne przeprowadzone w 100 przedsiębiorstwach. Autorzy omówili specyfikę pracy projektowej i specyfikę zarządzania zespołem projektowym. Następnie przeprowadzono przegląd literatury dotyczący kompetencji kierownika projektu i stylów kierowania projektem. Zidentyfikowano trzy ważne kompetencje, które odróżniają kierowników projektu pracujących w organizacjach stricte projektowych od kierowników zarządzających projektami na potrzeby wewnętrzne organizacjach, tj. orientacja na osiągnięcie, wrażliwość, praca zespołowa i współpraca. Analiza stosowanych i pożądanych stylów kierowania wskazała, że członkowie zespołów projektowych w obu typach organizacji zorientowanych na projekty, preferują demokratyczny styl kierowania w poszczególnych fazach realizacji projektu.

Słowa kluczowe: zarządzanie projektami, kompetencje, kierownik projektu, sukces projektu.

Biographical notes

Katarzyna Grzesik – assistant professor at Wrocław University of Economics, Department of Economics and Organization of Enterprises. She holds a Ph.D. degree in management science. Her research interests are in the issues of leadership in an organization, manager’s work, human resource management, and decision making in an organization. She has written over 30 papers in these areas.

Katarzyna Piwowar-Sulej - Dr. hab., associate professor at Wroclaw University of Economics (Department of Labour and Capital). Her research interests focus on human resource management in project-oriented enterprises and the development of innovation-oriented work environments. She has experience in conducting HR projects (e.g., application of IT systems in HR processes) and managing HR departments. Author of more than 100 publications and active participant of more than 50 conferences.