Aleksandra Wąsowska, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, University of Warsaw, Faculty of Management, ul. Szturmowa 1/3, 02-678, Warsaw. E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

This paper explores the evolution of export barriers along the firm’s internationalization process. Based on a sample of 7,515 European SMEs, we investigate the differences perceived by different groups of firms: companies uninterested in exports, future exporters, pre-exporters, experimental exporters, involved exporters, active exporters, committed exporters and failed exporters. We study both external barriers (i.e. arising from the environment in home and foreign markets) and internal barriers (i.e. related to the company’s resource endowment, marketing and strategy). We find statistically significant differences between some of the studied groups, thus supporting the notion that the perception of internationalization barriers changes along the firm’s lifecycle.

Keywords: export barriers, internationalization process, SMEs, Europe.

INTRODUCTION

The perception of export barriers by a company’s decision-makers is one of the key factors shaping the internationalization behaviour of firms (Artega-Ortiz & Fernandez-Ortiz, 2010). More specifically, it has an influence on the decision to start exporting, increase commitment abroad or withdraw from a foreign market. Moreover, it has an impact on the overall internationalization path, delimitating ‘conventional’ internationalisers from international new ventures (Kahiya, 2013), that is, firms expanding abroad very early in their lifecycle (Oviatt & McDougall, 1994).

Extant research on barriers to internationalization yields a number of conclusive findings. First, internationalization barriers may be both internal (i.e. firm-specific) and external (i.e. environment-specific), and may relate both to home-country conditions and target-country context. These barriers may be classified in more details, with a number of possible classifications available (e.g., Artega-Ortiz & Fernando-Ortiz, 2010). Second, the perception of barriers varies across firms, depending on firms’ organisational characteristics, such as age (e.g., Leonidou, 1995b), as well as their country of origin (e.g., Cahen, Lahiri & Borini, 2016). Third, while export barriers hamper internationalization, they do not prevent it completely. Therefore, some non-exporters are able to overcome export barriers and enter the internationalization path. Some barriers are, however, residual in nature, and they continue to exist at subsequent stages of the internationalization process. Fourth, some authors indicate that the perception of export barriers varies at different stages of the internationalization process.

Although significant contributions to the literature on export barriers have been made, there are still important knowledge gaps. First, the majority of studies are based on relatively small samples from single countries, which limits the generalisability of findings (Kahiya, 2013). Second, while there are studies examining barriers along the internationalization process (e.g., Suarez-Ortega, 2003; Uner, Kocak, Cavusgil & Cavusgil, 2013), none of them includes the very specific stage: de-internationalization. Little is known about ‘failed exporters’, that is companies that tried to enter foreign markets or used to export, but withdrew from this activity. Moreover, there is a paucity of studies following the theoretical classification of export barriers into external and internal. Therefore, our understanding of the evolution of these two types of barriers over the internationalization process is limited.

In this paper we aim to fill the gaps identified in extant literature by investigating the evolution of internal and external export barriers over the internationalization process. Specifically, we formulate the following research question: do small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) at different stages of their internationalization process differ in their perception of internal and external export barriers? In conceptualising the internationalization process we follow the notion that both exporting and non-exporting are heterogeneous phases, and that different groups of non-exporters (e.g., future exporters and failed exporters) and exporters (e.g., experimental exporters, committed exporters) need to be treated separately. Thus, we compare 8 groups of firms, 4 of them non-exporters (uninterested in exporting, future exporters, pre-exporters, and failed exporters), and 4 of them exporters (experimental exporters, involved exporters, active exporters, and committed exporters). We focus on SMEs, following the notion that these companies are more affected by export barriers than their larger counterparts (Morgan & Katsikeas, 1997) and therefore the understanding of the perception of export barriers of SMEs is particularly relevant to both theory and practice (Artega-Ortiz & Fernandez-Ortiz, 2010).

The structure of the paper is as follows. We first present the review of literature on the internationalization process and barriers to internationalization, and we formulate our research hypotheses. We proceed with the overview of research methods applied in the paper. We then present the data analysis. We conclude the paper by providing implications for theory and practice of International Business (IB).

LITERATURE REVIEW

Internationalization process

Internationalization has been defined as ‘the process of increasing involvement in international operations’ (Welch & Luostarinen, 1988, p. 36) or ‘the process of adapting firm’s operations (strategy, structure, resources, etc.) to international environments’ (Calof & Beamish, 1995, p. 116). While the former definition is based on an assumption that firms increase their commitment to international markets, the latter permits a broader view in which commitment to foreign markets may be increased, decreased or even abandoned. Therefore, this definition encompasses not only international growth but also de-internationalization, which is ‘any voluntary or forced actions that reduce a company’s engagement in or exposure to current cross-border activities’ (Benito & Welch, 1997).

A number of internationalization models have been offered in the IB literature, depicting the ‘stages’ of the internationalization process. For example, Johanson and Wiedersheim-Paul (1975) propose a 3-stage model, including (1) no regular export activity/no resource commitment abroad, (2) exporting to psychologically close countries via independent reps/agents, (3) exporting to more psychologically distant markets/establishment of sales subsidiaries. Wiedersheim-Paul, Olson and Welch (1978) focus on non-exporters, dividing them into three groups, corresponding to their ‘internationalization stage’, i.e. (1) domestic oriented firms, with no willingness to start exporting, (2) passive non-exporters, exhibiting a moderate willingness to start exporting, (3) active non-exporters, very willing to start exporting. Cavusgil (1982) offers a 5-stage model, including pre-involvement (stage 1), reactive involvement (stage 2), limited, experimental involvement (stage 3), active involvement (stage 4) and committed involvement (stage 5). A number of other models have been reviewed by Leonidou and Katsikeas (1996) and Crick, Chaudhry and Batstone (2001). The underlying theoretical assumptions of the stage models have been outlined by the Uppsala scholars (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). They suggest that internationalization is gradual, since it is driven by experiential learning, needed to overcome the ‘liability of foreignness’ and the ‘psychic distance’ between the home market and the target country.

The ‘gradual’ models of internationalization have received a lot of criticism. A rich body of literature on ‘international new ventures’ (e.g., Oviatt & McDougall, 1994) and ‘born globals’ (e.g., Knight, 1996) questions the adequacy of ‘stage’ models to describe the behaviour of firms entering foreign markets at the early stage of their lifecycles and dynamically expanding abroad. Forsgren (2002) indicates numerous ways to overcome ‘psychic distance’, other than experiential learning (e.g., imitation, search, acquisition of foreign firms), which may allow faster internationalization. A wide body of IB literature grounded in the network-based view argues that business networks shape the firm’s internationalization process, offering a vehicle for accelerated internationalization (e.g., Chetty & Campbell-Hunt, 2003). This argument has been recognised by the Uppsala scholars who, in their revised model, acknowledge that the main theoretical barrier to internationalization is the ‘liability of outsidership’ rather than the ‘liability of foreignness’ (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009).

Cricks (2004) points at another limitation of the stage models, arising from the assumption that subsequent decisions made in this process lead to an increased commitment to foreign markets. Due to their forward-moving nature, these models do not take into account de-internationalization. As a consequence, such models overlook potential differences between different groups of non-exporters (e.g., companies not yet interested in foreign markets and companies which had entered foreign markets and failed). Ignoring the heterogeneities within the group of non-exporters undermines the understanding of export barriers perceived by companies at different stages of the internationalization process.

Barriers to internationalization

Export barriers, closely related to the concept of liability of foreignness (Kahiya, 2017), are typically defined as ‘any attitudinal, structural, operative or other obstacles that hinder or inhibit companies from taking the decision to start, develop or maintain international activity’ (Leonidou, 1995a, p. 31). The problem of export barriers, first indicated by Bilkey (1978), has been one of the key themes in IB literature ever since. Early studies on export barriers were conducted in the U.S. Rabino (1980) investigated the perception of export barriers by U.S. small high-technology firms. He revealed the importance of five major factors: paperwork, finding a distributor, non-tariff barriers, honouring letters of credit, communication with customers in the foreign markets. In a study on the U.S. paper industry, Bauerschmidt, Sullivan and Gillespie (1985) found four key categories of export barriers: strategic, informational, process-based and operational barriers.

Since the 1990s, a number of studies on export barriers have been conducted in more diverse country settings, including Finland, Greece, Brazil and Turkey. For example, Cahen et al. (2016) focus on barriers to internationalization perceived by Brazilian new-technology firms. Their study is based on a notion that barriers to internationalization are, to some extent, country-specific and that those perceived by emerging market firms are different from those faced by developed-market firms (Ojala & Tyrvainen, 2007). The study revealed that institutional barriers, organizational capability barriers and human resource barriers were crucial obstacles of internationalization (Cahen et al., 2016).

Leonidou (1995a) classified export barriers into two categories: internal (i.e. firm-specific, related to the company’s resource endowment and strategy) and external (i.e. environmental-specific, related to the home country context or conditions in the target market) (Leonidou, 1995a). Building on this broad typology, Artega-Ortiz and Fernandez-Ortiz (2010) proposed the following classification: knowledge barriers, resource barriers, procedure barriers, exogenous barriers. Leonidou (2004) provided a comprehensive analysis of export barriers faced by SMEs, based on a systematic review of empirical studies. Extending his previous classification, he identified major internal (i.e. informational, functional, marketing) and external (i.e. procedural, governmental, task, and environmental) barriers. An extensive overview of export barriers faced by SMEs, based on Leonidou’s classification, has been recently offered by Narayanan (2015).

Kahiya (2013) suggested that internal barriers arise from constraints relating to resources, management, marketing and knowledge. Resource-related constraints include limitations in short-term financing, shortages of labour skills, as well as insufficient production capacity. SMEs are particularly prone to resource-related constraints, due to the ‘liability of smallness’. Managerial-related constraints include lack of vision, fear of losing control (Hutchinson, Fleck & Lloyd-Reason, 2009), as well as a lack of ‘global mindset’ (Nummela, Saarenko & Puumalainen, 2004). Marketing-related constraints include both market entry barriers, such as an inadequate marketing budget, inadequate marketing information (Da Rocha, 2008) and lack of international reputation (Ratajczak-Mrozek, 2014) and marketing mix barriers, such as adaptation of products to the conditions of foreign markets. Knowledge-related constraints relate to insufficient knowledge of export procedures and foreign business practices (Kahiya, 2013), lack of information to locate and analyse foreign markets, as well as an overall lack of knowledge that would allow the identification of business opportunities (Mori & Munisi, 2012).

External barriers include constraints arising from the characteristics of the home market (e.g., remote location, lack of domestic infrastructure supporting internationalization), host-market (e.g., import duties, political risk) and industry (e.g., high level of competition) (Kahiya, 2013).

A large number of studies on export barriers focused on non-exporters. For example, Leonidou (1995b) found that for this group of firms, competition (both foreign and domestic) was the most important barrier to internationalization. However, while export barriers hamper internationalization, they do not have enough power to prevent it completely (Leonidou, 2004). Export barriers may be overcome by planning, gathering resources or entrepreneurial impetus. These measures may allow non-exporters to enter the internationalization path. However, some of the export barriers are residual and remain important even for firms that already pursue an internationalization path (Suarez-Ortega, 2003).

While export barriers exist at every stage of the internationalization process, their nature tends to vary across different stages (Morgan, 1997). Thus, a number of studies have analysed how the perception of export barriers changes along the internationalization process. The majority of studies in this research stream investigated differences in the perception of export barriers by internationalised and domestic firms. For example, in their study on Portuguese SMEs, Pinho and Martins (2010) revealed that the main barriers for non-exporters were related to the lack of market knowledge, lack of qualified export personnel and other HR resources, lack of technical suitability, degree of industry competition and lack of financial assistance. For exporters, the main barriers were related to warehousing and control of the physical product flow. Thus, barriers perceived by non-exporters are ‘strategic’, i.e. related to the lack of resources and market structure, while barriers relevant to exporters are ‘operational’ in nature. Also, barriers indicated by non-exporters are purely based on perception of international activity, while barriers indicated by exporters are more ‘experiential’, that is, they result from first-hand experience in international markets (Pinho & Martins, 2010).

Other studies investigated differences in perception of barriers between sporadic and regular exporters (Kaleka & Katsikeas, 1995), in companies with different market experience (Katsikeas & Morgan, 1994) and companies with different levels of export intensity (Sharkey, Lim & Kim, 1989). For example, Sharkey et al. (1989) found that while marginal exporters did not differ from non-exporters, a significant difference existed between marginal exporters and active exporters. Shaw and Darroch (2004) compared non-exporters, likely exporters and exporters.

In a study of the Spanish wine industry, Suarez-Ortega (2003) compared four groups of companies: uninterested non-exporters, interested non-exporters, initial exporters and experienced exporters. She found that the more advanced the internationalization stage, the lower the perceived export barriers. Moreover, the study revealed that the importance of different types of export changes over time. For uninterested exporters, resource barriers were the most important. For interested exporters, knowledge barriers were the most significant. The most significant difference between initial exporters and experienced exporters was marked by procedural barriers.

Uner et al. (2013) explored differences in perception of export barriers among born globals and firms at different stages of internationalization (i.e. domestic marketing, pre-export, experimental involvement, active involvement, commitment involvement). They address the question of whether export barriers are stable over time, that is, whether they remain the same at different stages of the internationalization process. They conclude that these barriers differ mainly for born global, and firms at the first stage of internationalization (i.e. domestic marketing and pre-export stage).

Kahiya and Dean (2016), based on a sample of New Zealand SMEs, tested a set of hypotheses on the relationships between export stage and the influence on export barriers. They studied four types of internal barriers (i.e. managerial focus and commitment, resource factors, marketing barriers, knowledge and experience problems) and three types of external barriers (i.e. export-procedure barriers, economic obstacles, political-legal constraints). They found that resource constraints, marketing barriers, knowledge and experience barriers, and export procedure barriers were ‘export stage dependent’ (Kahiya & Dean, 2016, p. 75) and that differences existed only when comparing the early and the very advanced export stages.

Based on the findings of previous studies, we expect that the perception of export barriers differs in subsequent stages of the internationalization process. We argue that the evolution of perceived external and internal barriers needs to be studied separately, due to the different nature (i.e. environment-specific versus firm-specific) of these barriers. Moreover, we believe that it is essential to include into the analysis the ‘last’ stage of internationalization - withdrawal from foreign markets. We expect that, upon internationalization failure, perceived export barriers (both internal and internal) will be higher than during the ‘export’ stages.

Thus, we formulate the following set of hypotheses:

- H1. Companies at different stages of the internationalization process differ in their perception of external export barriers. More specifically:

- H1a. Failed exporters perceive external export barriers as significantly higher than all other group of companies.

- H1b. Uninterested exporters perceive external export barriers as significantly higher than future exporters, pre-exporters and all groups of exporters.

- H1c. Future exporters perceive external export barriers as significantly higher than pre-exporters and all groups of exporters.

- H1d. Pre-exporters perceive external export barriers as significantly higher than all groups of exporters.

- H1e. For exporters, the perceived external export barriers decrease in the subsequent stages of internationalization, resulting in significant differences in perceived external barriers between exporters at different stages of internationalization.

- H2. Companies at different stages of the internationalization process differ in their perception of internal export barriers. More specifically:

- H2a. Failed exporters perceive internal export barriers as significantly higher than all other group of companies.

- H2b. Uninterested exporters perceive internal export barriers as significantly higher than future exporters, pre-exporters and all groups of exporters.

- H2c. Future exporters perceive internal export barriers as significantly higher than pre-exporters and all groups of exporters.

- H2d. Pre-exporters perceive internal export barriers as significantly higher than all groups of exporters.

- H2e. For exporters, the perceived internal export barriers decrease in the subsequent stages of internationalization, resulting in significant differences in perceived internal barriers between exporters at different stages of internationalization.

RESEARCH METHODS

In this study we use data collected by the Flash Eurobarometer survey, focused on the internationalization of European SMEs (European Commission, 2015). The survey covered 14,513 SMEs from the 28 European Union (EU) countries and 6 non-EU countries. It was conducted in June 2015 by the research agency TNS Political & Social, with the use of a computer-assisted telephone interview. Top executives with decision-making responsibilities in the company (e.g., CEO, general manager, financial director) were eligible as respondents.

The Flash Eurobarometer survey applies the general definition of SMEs used in official European statistics (e.g., Eurostat) (i.e. enterprises with less than 250 employees) (European Commission, 2015). In this study we apply an additional criterion, i.e. ownership structure (independence) (Coviello & McAuley, 1999), in order to account for the fact that dependent SMEs (i.e. those that are subsidiaries of larger corporations), ‘behave like large ones’ and are more open to international business than independent companies (Airaksinen, Luomaranta, Alajääskö & Roodhuijzen, 2015). Thus, from the Flash Eurobarometer database we select only independent SMEs. Moreover, we exclude companies from six non-EU countries covered by the survey. We exclude all the observations with missing data. Our final sample is composed of 7,515 independent SMEs from the EU-28.

The publicly available Flash Eurobarometer report (European Commission, 2015) presents distributions of answers to questions included in the survey, which are analysed at an aggregate level. For the purpose of the present study, we were granted access to raw, firm-level data collected within the project. We conducted our own operationalisation of variables and statistical analysis (using IBM SPSS), allowing us to answer our research question.

Following previous studies, we classify the studied companies into different categories, corresponding to their internationalization stage. First, following the arguments of Crick (2004), we account for the potential differences between various groups of non-exporters, differentiating between companies expressing no interest in exporting, companies planning international expansion in the future, companies currently trying to enter foreign markets and companies which have withdrawn from foreign markets. Thus, we use four categories of non-exporters: ‘uninterested’, ‘future exporters’, ‘pre-exporters’ and ‘failed exporters’. Second, we also categorize different groups of exporters, based on the foreign sales to total sales (FSTS) ratio, extensively used in the IB literature to indicate the export performance (Reid, 1982) and the overall importance of exports to a firm’s strategy (Lee & Yang, 1990).

In order to classify companies into different categories, we used the following questions from the Eurobarometer questionnaire: ‘Have you ever exported, tried to export or considered exporting your products, and/or services?’ (for non-exporters, i.e. companies which have not recorded any foreign sales) and ‘In 2014, approximately what percentage of your sales came from each of the following markets?’ (for exporters). Depending on the chosen answer, the classification was as follows: (1) uninterested (chosen answer: ‘You will probably never export.’), (2) future exporters (chosen answer: ‘You are considering it for the future’), (3) pre-exporters (chosen answer: ‘You are trying to do it now’), (4) experimental exporters (companies with FSTS below 25%), (5) involved exporters (FSTS ranging from 25% to 50%), (6) active exporters (FSTS ranging from 50% to 75%), (7) committed exporters (FSTS above 75%), (8) failed exporters (chosen answer: ‘You used to export but you stopped doing it.’ or ‘You tried, but you have given up.’). The characteristics of the studied sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

|

Frequency |

% of Total |

|

|

Industry |

||

|

Manufacturing (NACE category C) |

1825 |

24.3% |

|

Retail (NACE categories G) |

2431 |

32.3% |

|

Services (NACE categories H/I/J/K/L/M/N/Q/R/S) |

1918 |

25.5% |

|

Industry (NACE categories B/D/E/F) |

1341 |

17.8% |

|

Total |

7515 |

100% |

|

Size |

||

|

1-9 employees |

3264 |

43.4% |

|

10-49 employees |

2862 |

38.1% |

|

50-249 employees |

1389 |

18.5% |

|

Total |

7515 |

100% |

|

Internationalization stage |

||

|

Uninterested |

2507 |

33.4% |

|

Future exporter |

702 |

9.3% |

|

Pre-exporter |

213 |

2.8% |

|

Experimental exporter |

1971 |

26.2% |

|

Involved exporter |

576 |

7.7% |

|

Active exporter |

499 |

6.6% |

|

Committed exporter |

725 |

9.6% |

|

Failed exporter |

322 |

4.3% |

|

Total |

7515 |

100.0% |

Source: Own calculations based on raw data from Flash Eurobarometer (European Commission, 2015).

In order to measure export barriers, we used the following question from the Eurobarometer survey: ‘If your company were to export, tell me if each of the following difficulties would be a major problem, a minor problem or not a problem at all.’ Respondents were provided with a list of 12 potential export barriers. Following previous studies (e.g., Leonidou, 2004), for the purpose of this study we differentiate between internal barriers and external barriers. We define internal barriers as constraints relating to resources, management, marketing and knowledge (Kahiya, 2013). We define external barriers as constraints arising from the characteristics of the home market, host-market and industry (Kahiya, 2013).

Thus, both types of export barriers have been measured with six questions, assessed on a 3-point Likert scale. Internal barriers are measured with the following items: (1) The financial investment is too large, (2) Your company does not have specialised staff to deal with exports, (3) Your company does not know the rules which have to be followed (e.g., labelling), (4) Your company lacks the language skills to deal with foreign countries, (5) Your company does not know where to find information about the potential market, (6) Your company’s products and/or services are specific to your country’s market. (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.785). External barriers are measured with the following items: (1) Resolving cross-border complaints and disputes is too expensive, (2) The administrative procedures are too complicated, (3) Identifying business partners abroad is too difficult, (4) Delivery costs are too high, (5) Dealing with foreign taxation is too costly, (6) Payments from other countries are not secure enough. (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.806). Although export barriers are often measured on a 7-point Likert scale, for the present study, based on a large, international sample, we accept the 3-point scale. In doing so, we follow the findings of Jacoby & Mattell (1971) who compared scales with different number of scale points used for Likert-type items and found no statistically significant difference in reliability and validity across different rating formats. We therefore follow their conclusion that ‘three-point Likert scales are good enough’ (Jacoby & Mattell, 1971, p. 495).

In order to compare the effect of the internationalization stage on export barriers we use a one-way ANOVA. The details of this procedure are presented in the following section of the paper.

ANALYSIS

First, we calculated descriptive statistics presenting both types of export barriers in different groups (see Table 2).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

|

External barriers |

Internal barriers |

||||

|

N |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

|

|

Uninterested |

2507 |

2.092 |

0.646 |

1.956 |

0.603 |

|

Future exporter |

702 |

2.006 |

0.538 |

1.775 |

0.494 |

|

Pre-exporter |

213 |

1.782 |

0.540 |

1.648 |

0.496 |

|

Experimental exporter |

1971 |

1.687 |

0.532 |

1.484 |

0.450 |

|

Involved exporter |

576 |

1.684 |

0.506 |

1.442 |

0.435 |

|

Active exporter |

499 |

1.685 |

0.494 |

1.415 |

0.392 |

|

Committed exporter |

725 |

1.633 |

0.516 |

1.348 |

0.367 |

|

Failed exporter |

322 |

1.930 |

0.600 |

1.684 |

0.480 |

|

Total |

7515 |

1.859 |

0.602 |

1.661 |

0.554 |

Source: Own calculations based on raw data from Flash Eurobarometer (European Commission, 2015).

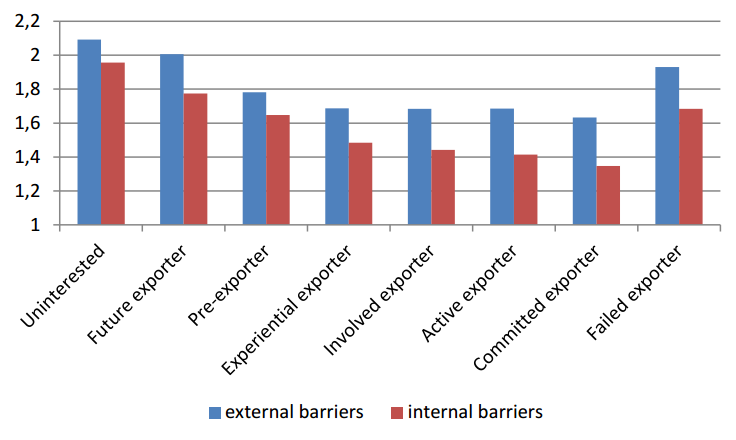

In order to enhance the understanding of the evolution of export barriers at different stages of the internationalization process, we drew the corresponding chart (see Figure 1). The analysis of descriptive statistics reveals that in all groups of companies external barriers are perceived as higher than internal barriers. Moreover, we observe a decline in perceived barriers (both external and internal) in subsequent stages of the internationalization process (with the exception of the last stage - barriers perceived by failed exporters are higher than for exporters). Also, the decline in perceived internal barriers over subsequent stages is more dynamic than the decline in perceived external barriers.

In order to test for the significance of differences between various groups, we then proceed to ANOVA analysis. We first used Levene’s test to verify the supposed homogeneity of variances across groups. Since the homogeneity assumption is not met, we use Welch’s F-test. Analysis of variance showed the main effect of a company’s internationalization stage on perception of both types of export barriers was significant: F(7.1596.578) = 119.297, p<0.001 for external barriers and F(7.1605.178) = 232.267, p<0.001 for internal barriers. Since the samples are of unequal size, in the post-hoc analyses we used the Games-Howell test (see Table 3).

Post-hoc analysis indicated that for failed exporters the perceived export barriers (both external and internal) were significantly lower than for uninterested companies. Moreover, there were no significant differences between failed exporters, future exporters and pre-exporters. However, failed exporters perceived external and internal barriers as significantly higher than all groups of exporters (experimental, involved, active and committed).

Table 3. Differences in export barriers perception - Games-Howell test

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

|

|

External barriers |

||||||||

|

(1) uninterested |

0.086** |

0.310*** |

0.405*** |

0.408*** |

0.407*** |

0.459*** |

0.162*** |

|

|

(2) future exporters |

-0.086** |

0.224*** |

0.319*** |

0.322*** |

0.322*** |

0.374*** |

0.076 |

|

|

(3) pre-exporters |

-0.310*** |

-0.224*** |

0.095 |

0.098 |

0.098 |

0.149** |

-0.148 |

|

|

(4) experimental exporters |

-0.405*** |

-0.319*** |

-0.095 |

0.003 |

0.003 |

0.054 |

-0.243*** |

|

|

(5) involved exporters |

-0.408*** |

-0.322*** |

-0.098 |

-0.003 |

-0.000 |

0.051 |

-0.246*** |

|

|

(6) active exporters |

-0.407*** |

-0.322*** |

-0.098 |

-0.003 |

0.000 |

0.052 |

-0.246*** |

|

|

(7) comitted exporters |

-0.459*** |

-0.374*** |

-0.149** |

-0.054 |

-0.051 |

-0.052 |

-0.298*** |

|

|

(8) failed exporters |

-0.162*** |

-0.077 |

0.148 |

0.243*** |

0.246*** |

0.246** |

0.298*** |

|

|

Internal barriers |

||||||||

|

(1) unintrested |

|

0.182*** |

0.308*** |

0.472*** |

0.514*** |

0.541*** |

0.608*** |

0.272*** |

|

(2) future exporters |

-0.182*** |

0.127* |

0.290*** |

0.333*** |

0.356*** |

0.427*** |

0.090 |

|

|

(3) pre-exporters |

-0.308*** |

-0.127* |

0.164* |

0.206** |

0.233** |

0.300** |

-0.036 |

|

|

(4) experimental exporters |

-0.472*** |

-0.290*** |

-0.164* |

0.042 |

0.069* |

0.136*** |

-0.200*** |

|

|

(5) involved exporters |

-0.514*** |

-0.333*** |

-0.206*** |

-0.042 |

0.027 |

0.094** |

-0.242*** |

|

|

(6) active exporters |

-0.541*** |

-0.359*** |

-0.233*** |

-0.069* |

-0.027 |

0.067 |

-0.269*** |

|

|

(7) comitted exporters |

-0.608*** |

-0.427*** |

-0.300*** |

-0.136*** |

-0.094** |

-0.067 |

-0.336*** |

|

|

(8) failed exporters |

-0.272*** |

-0.090 |

0.036 |

0.200*** |

0.242*** |

0.269*** |

0.336*** |

|

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Source: Own calculations based on raw data from Flash Eurobarometer (European Commission, 2015).

Therefore, we find support for hypotheses H1a and H2a only in relation to differences between failed exporters and exporters. Conversely, we find no support for the notion that failed exporters perceive export barriers as significantly higher than other groups of non-exporters. Contrary to our expectations, failed exporters perceive export barriers as significantly lower than uninterested exporters. No statistically significant differences exist between failed exporters and the two remaining groups of non-exporters (i.e. future and pre-exporters).

Companies uninterested in exports significantly differed from other groups in their perception of export barriers. More specifically, they perceived both internal and external barriers as higher than other groups. Therefore, we find full support for research hypotheses H1b and H2b.

For future exporters, internal and external export barriers were perceived as lower than in the case of uninterested companies and higher than in the case of pre-exporters, experimental exporters, involved exporters, active exporters, and committed exporters. Therefore, we find full support for research hypotheses H1c and H2c.

No statistically significant difference was observed between pre-exporters and experimental, involved and active exporters in their perception of external barriers. Pre-exporters differed only from committed exporters and they perceived external barriers as significantly higher. Therefore, research hypothesis H1d was supported only in relation to the difference between pre-exporters and committed exporters.

As for the perception of internal barriers, significant differences between pre-exporters and all groups of exporters existed. More specifically, pre-exporters observed higher internal barriers than all groups of exporters. Therefore, we find full support for hypothesis H2d.

Four groups of exporters (experimental, involved, active, and committed) did not differ in their perception of external barriers. Therefore, we find no support for research hypothesis H1e.

Some significant differences existed in the perception of internal barriers, thus providing partial support for research hypothesis H2e. More specifically, experimental exporters perceived internal barriers as significantly higher than active and committed exporters. Also, for involved exporters, internal barriers were higher than for committed exporters.

DISCUSSION

Our analysis revealed that perceived export barriers change during the internationalization process. However, not all the differences between the subsequent internationalization stages turned out to be statistically significant. Our findings shed light on the nature of barriers hampering the international growth of firms, from one stage to another.

Our results reveal that one group of firms - companies uninterested in exports - significantly differed from all other groups in perception of both external and internal barriers. We conclude that uninterested exporters constitute a particular group of companies, which perceive extremely high external and internal export barriers and are unlikely to enter the internationalization path in the near future. These companies account for 33.4% of our research sample. Given the sampling frame used in the Flash Eurobarometer study, this number is probably representative for the population of European SMEs.

Future exporters (9.3% or our research sample) differed from all other groups (both in terms of external and internal export barriers), with the exception of failed exporters. They perceived export barriers as higher than exporters and as lower than uninterested exporters. Interestingly, the difference between uninterested exporters and future exporters is much higher for internal barriers than for external barriers. We may conclude that the decline in the perceived internal barriers (e.g., resulting from the accumulation of resources) is the key prerequisite for gaining interest in exports. Internal constraints (e.g., lack of managerial skills, liability of smallness) seem to constitute the most important mental barrier that prevents managers from considering international expansion. This finding may be illustrated by two contrasting cases of Polish SMEs. The CEO of a company offering safety audit services, declaring no interest in internationalization, pointed to the role of internal export barriers: ‘in order to enter a foreign market we would have to significantly increase our production capacity, invest in advertising, build an international reputation. We simply cannot afford it’. The CEO of a Polish born-global company offering beauty products, declared in turn that the lack of mental barriers constituted a pre-requisite for a rapid international expansion of the company: ‘together with my business partner, we consider ourselves global citizens and we knew from the beginning that we didn’t want to focus on Poland, we wanted to go global’2.

Pre-exporters (2.8% of our sample) differed from the companies at the precedent stage of the internationalization process, i.e. future exporters, in both external and internal barriers. However, the major difference was observed for external barriers. Therefore, we may conclude that the key challenge in the transition from ‘future exporters’ (i.e. thinking about exporting) to ‘pre-exporters’ (i.e. actually starting to export) is to overcome external barriers (i.e. deal with administrative procedures, foreign taxation).

The transition from pre-exporters to experimental exporters is marked by a significant decline in internal barriers, with no significant change in external barriers. In a similar vein, the perception of external barriers does not change in a significant way in the subsequent stages of exporting (experimental exporters - involved exporters - active exporters - committed exporters). Even the most ‘distant’ stages of exporting (experimental exporters versus committed exporters) do not differ significantly in terms of the perception of external barriers. This is in line with the findings of Kahiya and Dean (2016), who concluded that some of the barriers (e.g., economic obstacles and political and legal barriers) were not ‘export stage dependent’.

While the most ‘distant’ stages of exporting (experimental exporters versus committed exporters) do not differ in terms of the perception of external barriers, they do, however, differ in the perception of internal barriers: significant differences exist between experimental and active exporters, experimental and committed exporters, as well as involved exporters and committed exporters.

Our findings reveal that companies which have decided to withdraw from export activity perceive export barriers (both internal and external) as significantly higher than current exporters. Interestingly, contrary to our expectations, failed exporters do not differ in their perception of export barriers from pre-exporters and future exporters. They are, however, significantly different from uninterested companies. Contrary to our expectations, for this group of companies internal and external export barriers are significantly lower than for uninterested exporters. We conclude that, although ‘failed exporters’ perceive export barriers as significantly higher than exporters, their attitude towards export activity may still be more favourable than for some non-exporters (i.e. uninterested companies). Considering the fact that their perceived export barriers are not higher than for future exporters and pre-exporters, we may conclude that ‘failed exporters’ may be prone to re-initiate export activity in the future. This conclusion is in line with the notion that some companies withdraw from foreign operations and, after a certain period of ‘time-out’, re-enter foreign markets (Welch & Welch, 2009). For example, in 2001, CVO Group, an online recruitment company from Estonia, temporarily suspended its operations in Russia, Bulgaria and Romania, only to re-enter these markets in the following three years (Visaak, 2006).

CONCLUSION

In this paper we investigated the evolution of internal and external export barriers during the internationalization process. We asked whether SMEs at different stages of their internationalization process differed in their perception of internal and external export barriers. We found significant differences between some of the studied groups, thus supporting the notion that the perception of export barriers evolves along the internationalization process. Our findings allow us to draw three important conclusions.

First, similar to Suarez-Ortega (2003), we observe a general decline of export barriers from one stage to another, with the exception of the ‘ultimate’ stage (i.e. export withdrawal), when perceived export barriers rise again. Thus, we conclude that the perception of export barriers is in fact an important factor differentiating one group from another.

Second, we conclude that the relative importance of different types of export barriers (i.e. internal versus external) changes along the internationalization process. At the very early stages of this process, internal barriers (e.g., lack of knowledge, financial shortages, and lack of qualified staff) play a major role, as they constitute a mental barrier preventing managers from considering international expansion. In the subsequent stage, external barriers become more important. The transition from ‘future exporters’ (i.e. companies considering expansion in the future) to ‘pre-exporters’ (i.e. companies actually undertaking efforts to enter foreign markets) depends mostly on overcoming perceived external barriers (i.e. finding a foreign partner). In the following stages of the internationalization process, internal barriers again become a crucial factor differentiating one group from another. A significant decline in perceived internal constraints along the internationalization process may be explained by the effects of learning and accumulation of resources (e.g., market knowledge, internationalization knowledge, and specialised staff).

Third, we observe that non-exporters are a heterogeneous group, encompassing firms uninterested in exporting, companies considering internationalization in the future, companies preparing to start exporting and companies that have already withdrawn from export activity. These sub-groups face different internationalization barriers, as well as a different set of incentives to undertake export activity. This observation should be taken into consideration by researchers who, contrary to common practice, should not treat ‘non-exporters’ as a homogeneous group. Also, public policy makers should be careful in designing public support programs for internationalization. Due to the heterogeneity among non-exporters; the significant role of mental barriers in initiating exporting; as well as the changing nature of export barriers along the internationalization process in the subsequent stages; the effectiveness of such programs may be very limited.

References

- Airaksinen, A., Luomaranta, H., Alajääskö,P., & Roodhuijzen, A. (2015). Statistics on small and medium-sized enterprises. Dependent and independent SMEs and large enterprises. Eurostat. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained

- Artega-Ortiz, J., & Fernandez-Ortiz, R. (2010). Why don’t we use the same export barrier measurement scale? An empirical analysis in small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(3), 395-420.

- Bauerschmidt, A., Sullivan, D., & Gillespie, K. (1985). Common factors underlying barriers to export: A comparative study in the US paper industry. Journal of International Business Studies, 16(3), 111-123.

- Benito, G., & Welch, L.S., (1997). De-internationalization. Management International Review, 37(2), 7-25.

- Bilkey, W.J. (1978). An attempted integration of the literature on the export behavior of firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 9(1), 33-46.

- Cahen, F.R., Lahiri, S., & Borini, F.M. (2016). Managerial perceptions of barriers to internationalization: An examination of Brazil’s new technology-based firms. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 1973-1979.

- Calof, J., & Beamish, P. (1995). Adapting to foreign markets: Explaining internationalization. International Business Review, 4(2), 115-131.

- Cavusgil, T.S., (1982). Some observations on the relevance of critical variables for internationalization stages. In M. Czinkota, & G. Tesar (Eds.), Export Management (pp. 276-286). New York: Praeger.

- Chetty, S., & Campbell-Hunt, C. (2003). Explosive international growth and problems of success among small to medium-sized firms. International Small Business Journal, 21(1), 5-27.

- Coviello, N.E., & McAuley, A. (1999). Internationalization and the smaller firm: A review of contemporary empirical research. Management International Review, 39(3), 223-256.

- Crick, D. (2004). U.K. SME decision to discontinue exporting: An exploratory investigation of practices within the clothing industry. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(4), 567-581.

- Crick, D., Chaudhry, S., & Batstone, S., (2001). An investigation into the overseas expansion of Asian-owned SMEs in the U.K. clothing industry. Small Business Economics, 16(2), 75–94.

- Da Rocha, A., Freitas, Y., & Silva, J. (2008). Do perceived barriers change over time? A longitudinal study of Brazilian exporters of manufactured goods. Latin American Business Review, 9(1), 102-108.

- European Commission (2015). Internationalization of small and medium sized enterprises. Flash Eurobarometer 421.

- Forsgren, M. (2002). The concept of learning in the Uppsala internationalization process model: A critical review. International Business Review, 11(3), 257-277.

- Hutchinson, K., Fleck, E., & Lloyd-Reason, L. (2009). An investigation into the initial barriers to internationalization: Evidence from small UK retailers. Journal of Small Business Development, 16(4), 544-568.

- Jacoby, J., & Mattell, M.S. (1971). Three-point Liker scales are good enough. Journal of Marketing Research, 8(4), 495-500.

- Johanson J., & Vahlne J.E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm: A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23-32.

- Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J-E. (2009). The Uppsala Internationalization Process Model revisited - from liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9), 1411-1431

- Johanson, J., & Wiedersheim-Paul, F. (1975). The internationalization of the firm: Four Swedish cases. Journal of Management Studies, 12(3), 305–322.

- Kahiya, E.T. (2013). Export barriers and path to internationalization: A comparison of conventional enterprises and international new ventures. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 3-29.

- Kahiya, E.T. (2016). Export stages and export barriers: Revisiting traditional export development. Thunderbird International Business Review, 58(1), 75-89.

- Kahiya, E.T. (2017). Export barriers as liabilities: Near perfect substitutes. European Business Review, 29(1), 61-102.

- Kaleka, A., & Katsikeas, C.S. (1995). Exporting problems: The relevance of export development. Journal of Marketing Management, 11(5), 499-515.

- Katsikeas, C.S., & Morgan, R.E. (1994). Differences in perception of exporting problems based on firm size and export market experience. European Journal of Marketing, 28(5), 17-35.

- Knight, G. (1996). Born global. Wiley International Encyclopaedia of Marketing. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781444316568.wiem06052/full

- Lee, C.S., & Yang, Y.S (1990). Impact of export market expansion strategy on export performance. International Marketing Review, 7(4), 41-51.

- Leonidou, L.C. (1995a). Empirical research on export barriers: Review, assessment, and synthesis. Journal of International Management, 3(1), 29-43.

- Leonidou, L.C. (1995b). Export barriers: Non-exporters perception. International Marketing Review, 12(1), 4-25.

- Leonidou, L.C. (2004). An analysis of the barriers hindering small business export development. Journal of Small Business Management, 42(3), 279-302.

- Leonidou, L.C., & Katsikeas, C.S. (1996). The export development process: An integrative review of empirical models. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(3), 517–551.

- Morgan, R.E. (1997). Export stimuli and export barriers: Evidence from empirical research studies. European Business Review, 97(2), 68-79.

- Morgan, R.E., & Katsikeas, C.S. (1997). Obstacles to export initiation and expansion. The International Journal of Management Science, 25(6), 677-693.

- Mori, N., & Munisi, G. (2002). the role of the internet in overcoming information barriers: Implications for exporting SMEs of the East African community. Journal of Entrepreneurship Management and Innovation, 8(2), 60-77.

- Narayanan, V. (2015). Export barriers for small and medium-sized enterprises: A literature review based on Leonidou’s Model. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 3(2), 105-123.

- Nummela, N., Saarenko, S., & Puumalainen, K. (2004). Global mindset - a prerequisite for successful internationalization? Canadian Journal of Administrative Science, 21(1), 51-64.

- Ojala, A., & Tyrvainen, P. (2007). Entry barriers of small and medium-sized software firms in the Japanese market. Thunderbird International Business Review, 49(6), 689-705.

- Oviatt, B. M., & McDougall, P. P. (1994). Toward a theory of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(1), 45–64.

- Pinho, J.C., & Martins, L. (2010). Exporting barriers: Insights from Portuguese small- and medium-sized exporters and non-exporters. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 8(3), 254-272.

- Rabino, S. (1980). An examination of barriers to exporting encountered by small manufacturing companies. Management International Review, 20(1), 67-73.

- Ratajczak-Mrozek, M. (2014). The importance of locally embedded personal relationships for SME internationalization processes - from opportunity recognition to company growth. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 10(3), 89-108.

- Reid, S. (1982). The impact of size on export behavior of small firms. In M. Czinkota, & G. Tesar (Eds.), Export Management (pp. 18-38). New York: Praeger.

- Sharkey, T., Lim, J., & Kim, K. (1989). Export development and perceived export barriers: An empirical analysis of small firms. Management International Review, 29(2), 33-40.

- Shaw, V., & Darroch, J. (2004). Barriers to internationalization: A study of entrepreneurial new ventures in New Zealand. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 2(4), 327-343.

- Suarez-Ortega, S. (2003). Export barriers: Insight from small and medium-sized firms. International Small Business Journal, 21(4), 403-420.

- Uner, M.M., Kocak, A., Cavusgil, E., & Cavusgil, S.T. (2013). Do barriers to export vary for born globals and across stages of internationalization? An empirical inquiry in the emerging market of Turkey. International Business Review, 22(5), 800-813.

- Vissak, T. (2006). Re-internationalization: A Conceptual Framework and Some Evidence from Estonia. University of Tartu: Faculty of Economic and Business Administration.

- Welch, C., & Welch, L. (2009). Re-internationalization: Exploration and conceptualisation. International Business Review, 18(6), 567–577.

- Welch, L.S., & Luostarinen, R. (1988). Internationalization: evolution of a concept. Journal of General Management, 14(2), 34-55.

- Wiedersheim-Paul, F., Olson, H. C., & Welch, L. S., (1978). Pre-Export activity: The first step in internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 9(1), 47-58.

Biographical note

Aleksandra Wąsowska is Assistant Professor of Strategic and International Management at the University of Warsaw. Her research interests include international entrepreneurship, strategies of emerging market multinationals, decision-making in the internationalization process and cross-cultural management. She graduated from the Faculty of Management (2005) and Faculty of Modern Languages (2006) at University of Warsaw and the Faculty of Psychology (2015) at SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities. In 2011 she defended her Ph.D. dissertation on ‘Resource-based determinants of internationalization of Polish listed companies’. She is a member of international academic associations (Academy of International Business, EIBA) and has worked as a business consultant in Poland, France and Portugal.