Anup Chowdhury, Ph.D., Professor and Chairperson, Department of Business Administration, East West University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Nikhil Chandra Shil, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Business Administration, East West University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Email: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Abstract

This study is about the exploration of innovative management control systems in the context of New Public Management (NPM) initiatives. NPM initiatives created the changes to the structure and processes of public sector organizations with the objective of getting them to run better. A government department in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) has been selected as the field for investigation. This study draws on a single theoretical perspective, Giddens’s structuration theory to understand the management control systems evolved in the researched organization. Qualitative research methodology is applied to obtain a better understanding of the phenomena. Case-based research method is used in developing a complete understanding of the relative role of controls in the management of organizational performance. In this study, it is argued that the researched organization has adopted various management control tools to improve its performance and demonstrate transparency and accountability. Some of the control tools it has adopted are the innovations in the public sector. It appears from the case that these adopted management control tools forced the researched organization towards better performance supporting the rationale of adopting New Public Management practices.

Keywords: innovation, management control systems, New Public Management, public sector organization, structuration theory.

INTRODUCTION

The performance of public organizations in industrial economies in the 1980s has been the target of severe questioning and pressuring for government cost cutting. The main reason for such questioning was the comparison with private sector standards of returns on investment and it turned public sector organizations from a service orientation to a commercial orientation (Mascarenhas, 1996). In this context the practitioners started to adopt new management approaches as the basis for improving performance in the public sector (Metcalfe & Richards, 1992; Osborne & Gaebler, 1992; Hughes, 1995; Girishankar, 2001; Robbins, 2007; Christiaens & Rommel, 2008; Broadbent & Guthrie, 2008; Alam & Nandan, 2008; Dooren, Bouckaert, Halligan, 2010; Walker & Boyne, 2010; Hoque & Adams, 2011). This new management approach in the public sector creates the changes to the structures and processes of public sector organizations with the objective of getting them to run better (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004). More precisely this new approach is centred on New Public Management (NPM) ideals (Hood, 1991; Dunleavy & Hood, 1994; Hood, 1995).

The term ‘New Public Management’ is used to describe the changing style of governance and administration in the public sector. The most definitive characteristic of the NPM is the greater salience that is given to what has been referred to as the three ‘Es’- economy, efficiency and effectiveness (Barrett, 2004). The NPM movement has emphasised the value of market efficiency in the public sector and stimulated various managerial innovations (Moon, 2000; Tooley, 2001; Luke, 2008; Christiaens & Rommel, 2008). NPM has shown a remarkable degree of consensus among the political leadership and opinion makers of various countries like Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom and Austria about the desired nature of change (Maor, 1999). In the UK it was government’s modernization agenda and was based on ‘New Public Financial Management’ (Broadbent & Laughlin, 2005). In the USA the state governments had also enthusiastically embraced the idea of managing for results. It represented a victory of NPM policy ideas transported from New Zealand, The United Kingdom and Australia (Moynihan, 2006).

A management control system is a broad term that encompasses management accounting systems and also includes other controls such as personnel or clan controls. Chenhall (2003) mentioned that Management control systems not only focus on the provision of more formal, financially quantifiable information to assist managerial-decision making but also concentrate on external information related to markets, customers, competitors, non-financial information, a broad array of decision support mechanisms and informal personal and social controls. It has been observed worldwide that the public sector organizations have been encouraged to develop market based mechanisms of control which are financial or budgetary, performance indicators, performance based pay, competition through privatization and contracting out, and the introduction of internal market models (OECD, 1995). To establish these types of control in public sector organizations it is necessary to allocate human, physical, technological and financial resources in a better coordinated way. A well designed management control system can play a pivotal role in this regard. Groot and Budding (2008) pointed out a good number of New Public Management (NPM) reforms related to the improvement of Planning and Control of government entities. Jansen (2004) also argued that adoption of NPM implies that the emphasis in management control of governmental organizations needs to change from a focus on information concerning input to information on other elements of the transformation process.

In the public sector there has been a long tradition that the public organizations provide utilities and services to the fabric of society. A movement away from this situation has emerged and emphasis is put on efficiency, economy, effectiveness, and streamlining managerialism. The public sector copied some of these control tools from the private sector. Some of the control tools they have come up with have been implemented on a modified basis and some of the control tools are unique to the public sector, and these constitute the innovation in the public sector. Mulgan and Albury (2003) defined innovation in the public sector as the creation and implementation of new processes, products and services and methods of delivery, which result in significant improvements in the efficiency, effectiveness or quality of outcomes. In the public sector some innovations are transformational because it represents a substantial departure from the past. Other innovations are incremental in nature.

During the last 30 years the three tiers of Australian government (Commonwealth, State and Local) have implemented a series of financial and administrative reforms linked to the new public management. Since the early 1980s the Australian public sector have undergone major changes in its philosophy, structure, processes, and orientation and the main objectives of these changes were to establish formal rational management, necessity for clear goals, corporate plans, internal and external accounting systems with clear responsibility lines for output performance measurement (Parker & Guthrie, 1993). Over the last two decades, in Australia, the public sector has come under increasing pressure to improve performance and demonstrate transparency. As a consequence of these pressures in a changing environment, public sector organizations have adopted management techniques and control strategies. These innovative management control systems are now widely used in the Australian public sector. Against this background the wide-ranging reforms and NPM approach in the Australian public sector offer a context for the present study.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Many authors have defined management control systems in many ways and as a result different typologies of management control have evolved to define management behavior. For example, Anthony and Govindarajan (2007) mentioned that in all organizations, managers are engaged in two important activities. One is planning and the other is control. Merchant and Van der Stede (2012) mentioned that management control includes all the devices or systems that managers use to ensure that the behaviors and decisions of their employees are consistent with the organization’s objectives and strategies. Simons (1995) defined management control systems as the formal, information-based routines and procedures that managers use to maintain or alter patterns in organizational activities. It can be seen that management control systems are a broader concept which include different components and are used for varying purposes.

Berry, Coad, Harris, Otley and Stringer (2009) found that during the last two decades, the concept of ‘new organizational forms’ has gained currency and transformation is more prevalent in some sectors, especially in the public sector. The authors claimed that from the 1980s onwards, new public management reforms have introduced into public sector organizations managerial processes from the private sector. These reforms open the door to more dynamic, action research type activities to observe the consequences of management control systems design and its use over a period of time following a change. In the light of reforms in the Australian public sector over the last thirty years, this study is about the exploration of innovative management control tools adopted in the public sector in the context of New Public Management (NPM) initiatives. A government department, in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) has been adopted as a field for investigation for the purpose of this exploration. The study will seek answers to the following research questions:

- How has the researched organization adopted innovative management control tools within their organization?

- In what ways are these innovative tools linked to the organizational actions of the researched organization?

- How have these tools contributed to and shaped new organizational culture within the researched organization?

RESEARCH METHOD, DATA COLLECTION AND DATA ANALYSIS

The organization investigated under this study is a government department in the Australian Capital Territory involved in service delivery. Fieldwork started in January 2008 and continued until June 2009. A follow-up period of fieldwork for the purposes of clarification took place from June 2010 to January 2011, in November and December 2011 and in February and March 2012. The method of data generation and collection adopted in this research was open-ended intensive field research using the interpretive tradition in qualitative research. The main data sources for this study were archival official documents and interviews. Direct observations of actors’ activities were also used in this study to supplement and complement the archival documents and interview data. In this case study, documentary evidence provided an important data source. The researchers were interested to explore people’s perceptions and these came out of interviews. The epistemological position also influenced the researchers to conduct interviews because it allows a legitimate or meaningful way to generate data by talking interactively with people, to ask them questions, to listen to them, to gain access to their accounts and articulations, or to analyse their use of language and construction of discourse (Mason, 2002). The interview method used in this study was unstructured and open-ended. Any research involving human and animal subjects requires ethical clearance from the relevant institution (Hoque, 2006). The present research, as it involved human subjects, was approved by the Committee for Ethics in Human research at the University of Canberra, Australia. At the very beginning of each of the interview sessions the researcher discussed the background issues with the participant in an informal way according to the respondents’ characteristics (say for example, job position). Before conducting the interviews one of the researchers listed the discussion issues. However, during the interview sessions, they were not followed up in a fixed order. The duration of these interviews were about an hour on average. The interview proceedings were recorded on a voice recorder with the consent of the participant. For safety reasons, back-up notes were also taken and checked and compared when the transcriptions were made. The interview tapes were transcribed later word for word. Key interview transcripts were fed back to the respective interviewees to establish the validity of the interview data.

Direct observation was also used in this study to supplement and corroborate the archival documents and interview data. In this study, observation data came from casual watching and attending a number of informal meetings and information sessions within the department. One of the researchers attended five morning tea sessions where he observed that staff were involved in discussing and debating organizational matters. It helped the researcher to gain first-hand information about the organization.

In qualitative research, data analysis requires that the researcher be comfortable with developing categories and making comparisons and contrasts (Creswell, 2007). In this study, the researcher analyzed data using the approach provided by Miles and Huberman (1994). In the first stage data reduction was done. In this research, the researchers organized the data first from the interview transcripts and then from field notes. Then the transcripts were printed and researcher marked the key points and made a summary. After that the data chunks were coded manually, focusing on themes from the research questions and the theoretical framework chosen for the study. The field notes taken during the observation were organized according to the themes. The documents collected during the field work were also organized at this stage. The second major flow of analysis activity was ‘data display’. At this stage the researchers displayed the interview transcripts and the field notes into broad groups. These groups were NPM, management control systems, innovative techniques. The purpose of the display was for an immediate access. It helped the researcher to see what happened in the researched organization. It also helped to find out the main direction and missing links of the analysis. The third stream of analysis activity was conclusion drawing and verification. It aided the analyst to interpret displayed data and to test the findings. At this stage, the researchers developed an in-depth understanding of the data and searched for other possible explanations for the data to make conclusions. Provisional conclusions were tested for verification purposes. In this study, the researchers tested the findings against the theoretical framework and reviewed understanding of the phenomena which they gathered from the organization against this theoretical framework.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE STUDY

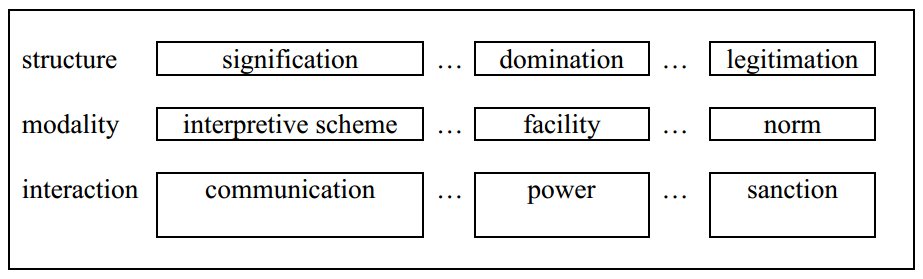

Some scholars argued that a prior theoretical stance may bias or limit the findings (Eisenhardt, 1989; Flinders, 1993; Layder 1995). The critics claimed that adopting a pre-determined theory in a research can be more robust because these theories have already been tested in previous research. However, supporters in favour of adopting a prior theoretical framework in research (for example Alam & Lawrence, 1994; Lodh & Gaffikin, 1997; Quattrone & Hopper, 2001; Baxter & Chua, 2003; Hoque, 2005; Gaffikin, 2007; Berry et al., 2009) argued that in conducting research on organizational practices, it is legitimate to use a wide range of theoretical approaches to explain such activities. In qualitative research, a useful theory helps to organize the data (Jorgensen, 1989; Lodh & Gaffikin, 1997; Llewelyn, 2003; Irvine & Gaffikin, 2006; Cooper, 2008; Maxwell, 2009; Jacobs, 2012). The view taken in the present research assumes that theory is a framework for viewing the social world in a way that is too general, too broad and too all-encompassing to be confirmed or refuted by empirical research (Cooper, 2008). It is also assumed in this research that when knowledge is gathered with the help of theory, there is a potential for data coherence and control, which prevent the researchers from collecting an unsystematic pile of accounts (Kaplan & Manners, 1986; Bogdan & Biklen, 1982). Over the last two decades it was observed that a series of alternative approaches has been used in qualitative research. One of these approaches is motivated by interpretive sociology (Schutz, 1967). Interpretive perspective epistemologically believes that social meaning is created during interaction and people’s interpretations of interactions (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2006; Cresswell, 2007; Gaffikin, 2008). Chua (1988) argued that interpretive sociology refers to an intellectual tradition which focuses on the constructive and interpretive action of people. The present study has adopted an interpretive approach and used Giddens’s structuration theory to understand how management control systems are implicated in social setting. The epistemological and ontological belief also inspired the researchers to adopt Giddens’ structuration theory in this study. The following Figure 1 shows Giddens’s structuration framework.

Source: Giddens (1984)

The third line of the Figure refers to the elements of interaction: communication, power and sanction. The second line represents modalities which refer to the mediation of interaction and structure in processes of social reproduction (Giddens, 1984). Here modalities are interpretive scheme, facility and norm. Those on the first line are characterizations of structure, signification, domination and legitimation. Signification refers to the communication of meaning in interaction. It is the cognitive dimension of social life which has interpretative schemes. Interpretive schemes are ‘standardized elements of stock of knowledge, applied by actors in the production of interaction’ (Giddens, 1984). In the signification structure, agents draw upon interpretative schemes in order to communicate with each other and at the same time reproduce them. In the domination structure the use of power in interaction involves the application of facilities. The facilities are both drawn from an order of domination and at the same time, as they are applied, reproduce that order of domination (Giddens, 1984). The final structure is that of legitimation which involves moral constitution of interaction, and the relevant modality here are the norms of a society or community which draw from a legitimate order, and yet by that very constitution reconstitute it (Giddens, 1976). These three structures constitute the shared set of values and ideals about what is important and should happen in social settings. Giddens (1976, 1979, and 1984) identified that actors are not simply social dupes governed by independent structures, but rather as existential beings that reflexively monitor their conduct and make choices in social settings.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

It has already been mentioned that the research site of this study was a governmental department in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). This department is involved in service delivery and was established in 2002. It has responsibility for a wide range of programs and policies which deliver essential services to individuals, families and the whole ACT community. The findings of the study indicate that the ACT Government has given the department wide responsibility to provide, or fund, human services for the Canberra community. In addition to these responsibilities, they have an obligation to implement formal agreements with other Australian governments and comply with laws passed by the ACT Legislative Assembly. The department works in partnership with community, private sector and government agencies in the delivery of the human services. Field study reveals that the department has three major wings. One of the wings is committed to increase the social, economic and cultural participation of all people in the ACT community. During the year 2010-2011 the major wing of the department administered $74 million worth of services (Disability Housing and Community Services [DHCS], 2010-2011). The second wing has its principal objective to provide people affected by housing stress and social and financial disadvantage with safe, affordable and appropriate housing that responds to their individual circumstances and needs. In the financial year 2010-2011, 23,245 people received affordable accommodation in public housing through 11,483 tenancies. The third wing works in partnership with the community to provide family and community support and care and protection services to children, young people and their families in the ACT. In 2010-2011 this wing dealt with $33 million (DHCS, 2010-2011).

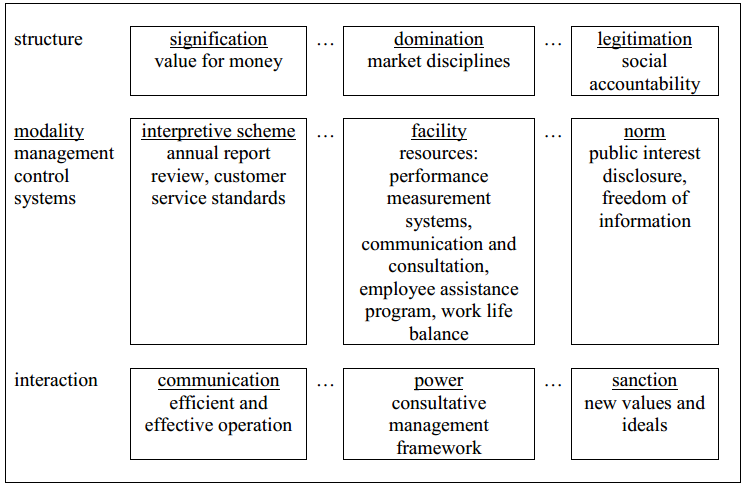

Observation from the field indicates that the researched organization has implemented a wide range of management control tools. Some of these are considered as the innovations in the public sector. These innovative management control techniques and tools are the results and action control mechanisms of the researched organization. For example; annual report reviews, performance measurement system, customer service standards, public interest disclosure, freedom of information, etc. Further, it has also been observed that there are some cultural control mechanisms in the researched organization, for example, communication and consultation, employee assistance program, work life balance, etc. These are considered as the innovative cultural control tools in the public sector.

The main objective of this research is to explore how the researched organization has adopted innovative management control tools within their organization and how these tools inspired the researched organization in their day to day administrative action. Observation from the field indicated that this reforms process shaped new organizational culture within the researched organization. A central element in the Australian public sector reform policy during the last thirty years is management for results. It has created a culture of clear and precise definition of program and organizational objectives for the Australian public sector financial managers. The objective to implement this control system in the researched organization is to inform the employees about the goals of the organization. The evidence from the field shows that the department has benefited enormously from adopting a results oriented approach to financial management. It has also helped probity and accountability for spending taxpayers’ money and at the same time ensured parliamentary scrutiny of the financial details of its operation. The main result oriented approaches were annual report review and performance measurement system.

Annual report review

The findings of the research demonstrate that annual report reviews in the public sector differ from the private sector. In the private sector, the annual report review is done at the shareholder’s annual general meeting, but in the public sector this review is open to public scrutiny. The researchers observed that every year after the publication of the annual report of the department, the Standing Committee on Community Services and Social Equity in the Legislative Assembly schedules annual report review hearings for the Department. It is one of the alternatives of market-based management control systems evaluation that take place in the private sector. It has created a new culture within the organization. It is also the formal accountability system that the department uses to inform the public about the management performance as a government agency in the implementation of government policy. This system helps the department in serving and contributing good governance. Organizational documents support that, in these hearings, the Standing Committee seeks evidence by asking the relevant government ministers and departmental officers to explain the issues and activities related to the Output Classes in the annual report. This annual report review brought a challenge to the signification structure of the researched organization and required the implementation of new interpretive schemes (Giddens, 1979, 1984). A change to the structure of meaning and new signification was seen in the department. According to Giddens (1979, 1984) in the department a competing interpretive scheme of signification became apparent. New public management brought a challenge to the signification structure of the department and required the implementation of these new interpretive schemes. It is evident that to meet the demands of the NPM initiatives, the department implemented annual report review devices as interpretive schemes in their organization. In the department, this new interpretive scheme is the management control system which mediates between the signification structure and social interaction (Giddens, 1979, 1984) in the form of communication between managers and employees.

Performance measurement systems

Observation data reveals that the main objective of the reforms in the researched organization is to promote a culture of performance in the public sector. These are very important for them, as one of the senior executives commented:

If the public are not happy with our service they can go to a politician and take the issue up and there is also the media scrutiny because of the focus of the political process. So there is a form of scrutiny and I think we are much more exposed than the corporate world.

It is evident that the department uses the bottom–up approach in decision making. In the context of public policy, plans are informed by community expectations. These community expectations are an innovation in the public sector which is different from the private sector. This is integral to the domination system (Giddens, 1979, 1984) for the department’s managers. In the researched organization, the managers are absolutely accountable for their performances.

Evidence from the field indicated that the researched organization uses financial and non-financial performance measures in their organization to develop individual and overall business improvement at the operational and strategic level. Financial performance evaluation and reporting have long been used to help evaluate the relative success of business activities (Alam, 2006). To obtain better results, the conventional language of accounting (performance standards) became part of the frame of meaning used to make sense of activities at the researched organization. Though it is in the initial stage, the department uses the performance measurement system as one of a number of tools that direct and support organizational change and performance. As one senior executive of the organization put it:

We have a reporting system to the government around key financial performance indicators. I think there are some challenges and some work to do in getting around and making it right. We have the beginning but some of these things, particularly in the service organization, are difficult to quantify. But, increasingly, as we are connected into the debate nationally with other jurisdictions, we are getting more unified views about the things.

In the public sector there has been a long tradition that public organizations provide utilities and services to the community and have been seen as the fabric of society. These organizations are funded by government budget allocation raised from taxation and provide supply services and utilities which is part of the infrastructure of society. No attempt has been taken to measure efficiency or effectiveness of government spending for a long time. This was the old structure of the traditional public organizations. To cope with the changing environment, and to meet the demands of the economic rationality of the new public management, the department implemented these performance measurement systems. The opinion expressed by another senior executive of the department confirmed this view:

In our department every single branch has financial performance indicators; they are published in the budget papers annually. There are targets and actual results and we have really adopted those things as an indicator. People in the department then have 12 months to try and reach the target.

Here, it can be argued that performance measurement systems provide bindings of social interactions in the organization across time and space and therefore, these control systems are considered as social practices. It acts as modalities of the structure. These modalities are the means by which structures are translated into actions. The modalities of performance measurement systems are interpretive schemes, and norms of the researched organization. These modalities explain how interaction is affected. According to Giddens (1979, 1984) these control systems are viewed as the modalities or procedures of structuration which mediates between the (virtual) structure and the (situated) interactions.

Modell (2004) argued that public sector organizations have come under increasing criticism for placing too much attention on financial control and suffering from excessive proliferation of performance indicators. Modell (2004) concluded that non-financial performance management indicators and goal-directed multidimensional models may gradually replace the myth that public service provision may be improved by a heavy reliance on financial control. The selected researched government department is not an exception in this regard. The department’s major priorities are: delivering the highest possible level of client services incorporating community, business and government as partners. It is evident from this research that the department has developed non-financial performance measures. These measures are related to accountability indicators for every output classification. These indicators show that the department uses targets, estimated outcomes and the subsequent year’s targets. The non-financial performance measurement system of the department is described by one of the junior staff in the department, as follows:

We have a number of financial indicators that are linked to an output based budget. There are four outputs to the department that are further broken up to output classes and they all have strategic indicators placed against them which are mostly non-financial.

The department evaluates their non-financial performance through a client satisfaction survey. This is done independently and which is not done in the private sector. There are different ways that the department conducts surveys and the different indicators used to determine how or what the department are doing. This was evidenced in comments by one of the mid-level executives of the Department:

Each of our agreements within the community sector has a performance measure and there is a quality assurance system in there. There are also performance issues in meeting the outputs we have purchased. There definitely needs a lot more work on measuring the qualitative attributes. We do those processes to ensure that there is accountability through our agreements. We do satisfaction surveys on our client. So if the clients are satisfied we can readily say our performance is good. These measures are reported annually in the annual report and we are accountable to government as well.

According to Giddens (1979, 1984), the domination dimension of social life includes facilities through which actors draw upon the structure in the exercise of power. In a broad sense power is considered as the ability to get things done, and in a narrower sense it simply implies domination (Busco, 2009). Macintosh and Scapens (1990) argued that resources facilitate the transformative capacity of human action (power in the broad sense), while at the same time providing the medium for domination (power in the narrow sense). In this sense, performance measurement systems are conceptualized as socially constructed resources, which can be drawn upon in the exercise of power in both senses. In the department, performance measurement systems are facilities that management, at all levels, uses to coordinate and control other participants. Management is able to use their power to legitimate the employment of the organization’s allocative resources in the interests of employees. These are the material phenomena which the department provides to its members to exercise power. In the researched organization, this performance measurement system acts as a modality of the structure. Therefore, a new domination structure of performance appeared in response to new public management initiatives, to challenge the traditional view of public sector.

It is also evident that in the department a number of administrative control systems have been introduced to guide the employees and to ensure the best interests of the organization. These control devices are customer service standards, public interest disclosure and freedom of information.

Customer service standards

The department has adopted Australian Capital Territory Government’s Customer Service Standards 1999 for its internal service delivery areas. These standards are different from the private sector. These standards focus on customer needs and have a link to organizational improvement mechanisms within the service delivery areas. These standards are adopted by the department to control the actions of its staff also. As a public organization, the department continuously concentrates on public needs and, in comparison to the private sector, it is difficult to follow the standards. These Customer Service Standards guide its staff in dealing with difficult customers. These customer service standards become integral to the signification systems (Giddens, 1979, 1984) for the department’s manager. Field study revealed that managers of the relevant areas regularly review the standards that have been set and determine where improvements are needed. The department also adopted best practice complaints handling standards. The department provides resources for complaints handling and arranges sufficient training and support to ensure that complaints are dealt with efficiently. They also monitor and review customer satisfaction and this improves customer and organizational outcomes. It is evident that customer service standards are the new signification system which is the rules or aspects of rules (Giddens, 1979). Evidence from the field shows that in the department, the new interpretive scheme (Giddens, 1979, 1984) is the customer service standards which mediate between the signification structure and social interaction in the form of communication between employees and citizens. It appears that in the department these interpretive schemes are the direct outcome of the new public management ideals and was implemented to establish the principle - value for money. Managers in the department use these interpretive schemes to interpret past results, take actions and make plans. Managers also use these control devices to communicate meaningfully with its employees and to influence the individual towards organizational goal achievement.

Public interest disclosure

The NPM approach forced public organizations to express the values and preferences of citizens, communities and societies (Bourgon, 2008). Public interest disclosure is an innovation in the accountability system of a public organization which is used in the public interest (Mulgan, 2000; Kinchin, 2007; Bourgon, 2008). Organizational documents suggests that the researched department implemented control mechanism for public interest and adapted the ACT government Public Interest Disclosure Act 1994 (ACT, 1994). It ensures that all disclosures made in the public interest are investigated thoroughly. Public interest disclosure of the researched organization has created a new structure of legitimation (Giddens, 1979, 1984) and attributed to everyday activity at the researched organization. The department receives complaints about the actions of the department, its officers or other persons employed by the department. These complaints are referred to Public Interest Disclosures. It is evident that this disclosure is directly related to the researched organization’s goals and objectives achievements. Drawing on the values, context and strategic themes, the department is accountable to the clients and provides opportunities for regular feedback on any aspect of their contact with their service. In this sense, public interest disclosure helps towards its outward accountability.

Freedom of information

In the public sector, citizens are entitled to access all information from the public organization. It is different from the private sector and acts as an outward accountability mechanism of the public sector. Freedom of Information (FOI) legislation may be used in this case (Mulgan, 2000). FOI laws have made inroads into the older conventions of secrecy in the governmental agencies (Corbett, 1996; Roberts, 2000; Piotrowski & Rosenbloom, 2002). At the Commonwealth level in Australia, the Freedom of Information Act was passed in 1981 and came into effect in December 1982. It was one of the reforms of the Federal government of that time. In the Australian Capital Territory this Act was passed in 1989. In the light of the economic rationality of the new public management the researched government department has adopted The ACT Freedom of Information ACT 1989. Roberts (2000) argued that the freedom of information law gives citizens the right of access to government information. The FOI Act provides the legal right to the public to see the documents held by ACT ministers and the department. It strengthens accountability to clients and to the law which is derived from the new public management. Freedom of information is not seen in private sector practice and it is the innovation of the public sector.

The legitimation structure (Giddens, 1979, 1984) in the department is the new moral obligation of the public service. Here, public interest disclosure and freedom of information are important and the department is accountable for acting in the public interest. This new public accountability is not providing information or answering questions. It includes setting goals, providing and reporting on results and the visible consequences for getting things right or wrong. The department developed these innovative control tools, which are designed to help employees make informed choices about their behavior and to communicate the department’s core values of honesty, respect, confidentiality, professionalism and fairness. Employees apply these new values in performing their duties. The department has adopted some innovative cultural and people control mechanisms. These are communication and consultation, employee assistance program and work life balance.

Communication and consultation

From the field it has been observed that the researched department has created a culture of effective consultation and employee participation in the decision process. Interviews and examination of the organizational documents supports that it has both communicative and constructive roles in the business. For example, every individual throughout the organization is given an opportunity to take part in the planning process. It helped to improve communication through a mutual exchange of ideas and experiences. This attitude is consistent with the findings of Maddock (2002), Farnham, Horton and White (2003) and Brown, Waterhouse and Flynn (2003), that public management and new forms of human resource management have produced involvement with individual elements in the decision-making process. Documentary evidence suggests that the researched organization provides relevant information to assist the employees and the unions to understand the reasons for the proposed changes, and the likely impact of these changes, so that the employees and the unions are able to contribute to the decision making process (DHCS, 2007). In the researched organization, communication and consultation is viewed as an authoritative resource in the hands of the senior executives, which facilitates the transformative capacity of action within the organization.

In the department, the communication and consultation system is involved in the relations of domination and power, and as power is the ability to get things done, management of the department uses its cultural control systems to provide facilities in the form of communication and consultation. Management of the department uses their power to legitimate the employment of the organization’s allocative resources in the interests of employees. These are the material phenomena which the department provides to its members to exercise power.

Employee assistance program

One of the reform initiatives in the Australian public sector is consistent with the requirement for industrial democracy in the workplace. In that provision a consultative structure is to be implemented in organizations. The major issue addressed under the new structure is that of stress in the workplace (Martin & Coventry, 1994). According to these initiatives, and in line with NPM, the researched organization has introduced the Employee Assistance Program. New public management introduced this new form of human resource management that operates as an early intervention program in the workplace. It provides independent, confidential and professional counseling services. In the researched organization, this program is designed to address and improve employees’ personal life and work performance which is adversely affected by personal or work-related problems. This finding is consistent with the results observed by Arthur (2000) that employee assistance programs increasingly provide benefits to reduce the effects of ‘stress’ on individuals and organizations; provide a ‘management tool’ to improve workplace performance and productivity; and respond to critical incidents.

The old bureaucratic tradition of public management dealt with a collective form of employee assistance. However, new public management led to a shift from collective assistance to individual needs (Farnham, Horton & White, 2003). The researched organization established a consultative structure that solves individual needs and this program includes communication and interpersonal problems, emotional, marital or family and relationship difficulties, alcohol or substance abuse, career planning and stress management and financial and lifestyle worries. In such situations the staff member could benefit from this counseling. In the department, the role played by actors and their interaction with the structure and social processes have been identified. The department has adopted and provided allocative resources through employee assistance program for the domination of the employees.

Work life balance

The researched government department developed a culture of flexible working arrangements which is helping employees changing their hours of work suited to their situations, job sharing and home based work. Organizational documents suggest that the department uses this control mechanism to recognize the needs of its staff to balance work, family and other personal commitments. It provides a framework to assist managers and staff with the negotiation, implementation and review of flexible work options (DHCS, 2006). This attitude supports the findings observed by Perrons (2003) that flexible working patterns and home working are compatible with a work-life balance and neither of which affected the volume of work. It is the allocative resources (Giddens, 1984) which the managers of the researched organization provide to its employees in the form of command over objects and use as a domination modality. Most of the employees interviewed believed that the researched organization has established a work-life balance culture to ensure a supportive workplace, along with a healthy and resilient work team, which contributes significantly to a productive work environment.

In the department, communication and consultation, an employee assistance program and work life balance, act as a modality of structuration. The cultural control system identifies a new set of values and ideals about approve and disapprove behavior. These ideals are the new ethos derived from the public sector reforms. The cultural control system in the researched organization acts as a modality of structuration. The department has developed this morality through the sharing of common meanings, values, norms and rituals by implementing new public management ideals within the organization.

Giddens’s Structuration Theory is used in this study to understand the innovative management control systems in the selected government department as part of their reform. This theory provided an understanding of the relationship between management control systems and the actions of the employees in the department. Public sector reforms brought a challenge to the signification structure of the department and required the implementation of new interpretive schemes. To meet the demands of the NPM initiatives, the department implemented control devices as interpretive schemes in their organization. In the department, the elements of the new interpretive schemes for significations are annual report review and customer services standards. According to Giddens (1979, 1984), the domination dimension of social life includes facilities through which actors draw upon the structure in the exercise of power. In a broad sense, power is considered as the ability to get things done and in a narrower sense, it simply implies domination. In the department, management control systems are facilities that management at all levels uses to coordinate and control other participants.

In the department the elements of domination dimensions are performance measurement systems, communication and consultation, an employee assistance program and work life balance. In the department, a new legitimation structure appeared in response to the new public management initiatives to challenge the traditional view. The legitimation structure in the department is the new moral obligation of the public service. Here, new public accountability is important and the department is accountable for acting in the public interest. The legitimation structure in the department consists of the normative rules and moral obligations of the social system. These are public interest disclosure and freedom of information. These ideals are the new ethos derived from the public sector reforms. Field study data reveals that the department developed new values and ideals which are designed to help employees make informed choices about their behavior and to communicate the department’s core values of honesty, respect, confidentiality, professionalism and fairness. Employees of the department apply these values in performing their duties. This behavior became integral to the legitimation system of the department (Giddens, 1979, 1984).

In the department, it is evident that management control systems are modalities of structuration in the three dimensions of signification, domination and legitimation. It shows how managers and employees make sense of organizational events and activities.

Giddens’ structuration theory is concerned with the relationship between the actions of agents and the structuring of social systems in the production, reproduction and regulation of social order. In the department, the role played by actors and their interaction with the structure and social processes have been identified. In the department, it is evident that these innovative management control systems are modalities of structuration in the three dimensions of signification, domination and legitimation. It shows how managers and employees make sense of organizational events and activities. These control devices are both the medium and the outcome of interaction because, in the organizational setting, these control devices are constituted by human agency and, at the same time, are also guided by them. Therefore, duality of structure is evident in the department.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The study is limited to the practice of management control systems in a government department in Australia. The characteristics of the government sector generally differ from the private sector in terms of profit motives, proprietary versus political interests, users and resource allocation process, external scrutiny, employee characteristics and legal constraints etc. However, it is evident from the study that the NPM initiatives forced the researched organization to promote innovative management control tools.

Another limitation of the present research is that it is a single case study and the findings cannot be generalized to a wider population. However, in this research, the single case study was the preferred method because the study was an attempt to understand, in-depth, how innovative management control systems were implicated in their wider organizational setting. It was not the objective to express a general overview of other organizations. As Stake (1995) argued, case study research is not a sampling research. He pointed out that a case study is expected to catch the complexity of a single case. Yin (2009) mentioned that the choice of designing single or multiple sites depends on the research question. In the present research, the researchers were interested to use a single site because it fits with the research questions. For another reason, multiple sites were not the option taken, as a multiple case study approach is used for a cross-site comparison (Eckstein, 1975; George, 1979; Hussain & Hoque, 2002) which was not the objective of this research.

Direction for future research

There are several implications of this study for future research. The financial and administrative reforms implemented in the public sector provide a key opportunity to study several issues. The present research explored how innovative management control technologies were implicated in a new public management environment. The insight that was gained is that there are not enough in-depth studies that have addressed and focused on these issues. Hence, there are many research possibilities in this area which will strengthen our knowledge and understanding.

The major strength of the present study is that it is an in-depth case study. However, it has been argued that in a single case study, findings cannot be generalized to a wider population. An interpretive study could be done incorporating another three or four Government Departments. A comparison of experiences of reforms on those government departments who have responded to various new public management initiatives could prove useful for policy makers.

This study has argued that the researched organization adopted innovative management control systems and changed their structures and behaviors to implement managerial reforms. A comparative case study of the management control systems of a private company and a reformed government department could be an interesting area for future research. It could considerably extend the stock of knowledge in this area.

The present research adopted a particular theoretical framework to analyze and understand data. This framework was used to explore and gain understanding of the control process that evolved in the researched organization. Similar studies could be conducted adopting other social or political theories and would undoubtedly enhance our current understanding of the theoretical and methodological perspectives in the context of new public management.

The study was focused on a developed country. A similar study could be conducted adopting a single case in a developing country and would increase our understanding about the factors that play a vital role in designing management control systems in a developing world’s public sector organization. In addition to that, a comparative study could also be done to explore the role of management control systems in the context of new public management initiatives in both developing and developed countries. It might also be fruitful to compare management control systems in changing public sector environments worldwide as this would provide an opportunity to disseminate information in this area.

CONCLUSION

Empirical evidence collected on the organization suggests that implementing these innovative control devices in the researched organization were a response to pressures from NPM initiatives in Australia. This study also showed that the researched department implemented a wide range of management control mechanisms to attain the economic rationality of the NPM. In the researched organization the driving imperative for innovation is the need to respond effectively to new and changing government and community expectations. It has been observed that the innovations in the organizations involve consultation, negotiation, cooperation and agreement across and within Federal departments, territory departments and the private sector. These innovative control mechanisms have brought economic logic into the researched organization and established a new type of management within the organization. These control devices are both the medium and the outcome of interaction because in the organizational setting these control devices are constituted by human agency and at the same time are also guided by them. The findings from this study reveal that the researched organization has been operating within the context of a range of reformed government policies, strategies and laws, as well as Commonwealth-State/Territory Multilateral and Bilateral agreements. Therefore, the primary catalyst in implementing these control tools in the researched organization is a number of government regulatory policies. These policies forced the selected government department to adopt a new culture which has more managerial elements in its nature.

References

- ACT Government. (1994). The Public Interest Disclosure Act. Australia: ACT.

- Alam, M., & Lawrence, S. (1994). A new era in costing and budgeting: Implications of health sector reform in New Zealand. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 7(6), 41-51.

- Alam, M. (2006). Stakeholder Theory. In Z. Hoque (Ed.), Methodological Issues in Accounting Research: Theories and Methods (pp. 207-222). UK: Spiramus Press Ltd.

- Alam, M., & Nandan, R. (2008). Management control systems and public sector reform: A Fijian case study. Accounting, Accountability and Performance,14(1), 1-28.

- Anthony, R. N., & Govindarajan, V. (2007). Management Control Systems. McGraw Hill Irwin, Boston Mass.

- Arthur, A. R. (2000). Employee assistance programmes: The emperor’s new clothes of stress management. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 28(4), 549-559.

- Barrett, P. (2004). Financial management in the public sector- how accrual accounting and budgeting enhances governance and accountability. Address to the Challenge of Change: Driving Governance and Accountability, CPA Forum 2004, Australian National Audit Office.

- Baxter, J., & Chua, W. F. (2003). Alternative management accounting research - whence and whither. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(2-3), 97-126.

- Berry, A. J., Coad, A. F., Harris, E. P., Otley, D. T., & Stringer, C. (2009). Emerging themes in management control: A review of recent literature. British Accounting Review, 41, 2- 20.

- Bogdan, R. & Biklen, S. (1982). Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. USA: Allyn and Bacon, Boston.

- Bourgon, J. (2008). The future of public service: A search for a new balance. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 67, 390-404.

- Broadbent, J., & Laughlin, R. (2005). The role of PFI in the UK government’s

- modernisation agenda. Financial Accountability and Management, 21(1), 75-97.

- Broadbent, J., & Guthrie, J. (2008). Public sector to public services: 20 years of contextual accounting research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(2), 129-169.

- Brown, K., Waterhouse, J., & Flynn, C. (2003). Change management practices- is a hybrid model a better alternative for public sector agencies? The International Journal of Public Sector Management, 16(3), 230-241.

- Busco, C. (2009). Giddens’ structuration theory and its implications for management accounting research. Journal of Management and Governance, 13(3), 249-260.

- Chenhall, R. H. (2003). Management control systems design within its organizational context: Findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28, 127-168.

- Christiaens, J. & Rommel, J. (2008). Accrual accounting reforms: Only for businesslike (Parts of) governments. Financial Accountability & Management, 24(31), 59-75.

- Chua, W. F. (1988). Interpretive sociology and management accounting research – A critical review. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 1(2), 59- 79.

- Cooper, G. (2008). Conceptualising social life. In N. Gilbert (Ed), Researching Social Life (pp. 5- 20). London: Sage Publications.

- Corbett, D. (1996). Australian Public Sector Management. NSW: Allen & Unwin.

- Cresswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. California: Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- DHCS (2006). Work Life Balance: Staff Guidelines. ACT, Australia.

- DHCS (2007). Union Collective Agreement 2007-2010. ACT, Australia.

- DHCS (2010-2011). Budget Paper No. 4. ACT, Australia.

- Dooren, W. V. Bouckaert, W.G., & Halligan, J. (2010). Performance Management in the Public Sector, London: Routledge.

- Dunleavy, P. & Hood, C. (1994). From Old Public Administration to New Public Management. Public Money & Management, 9-16.

- Eckstein, H. (1975). Case study and theory in political science. In F. I. Greenstein & N. W. Polsby (Eds.), Strategies of inquiry (pp. 79-137). Addison-Wesley.

- Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532-550.

- Farnham, D., Horton, S., & White, G. (2003). Organizational change and staff participation and involvement in Britain’s public services. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 16(6), 434-445.

- Flinders, D. J. (1993). From Theory and Concepts to Educational Connoisseurship. In D. J. Flinders and G. E. Mills (Eds.), Theory and Concepts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives from the Field (pp. 117-140), Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Gaffkin, M. (2007). Accounting research and theory: The age of neo-empiricism. Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal, 1(1), 1-19.

- Gaffkin, M. (2008). Accounting Theory: Research, Regulation and Accounting Practice. NSW: Pearson Education, Frenchs Forest.

- George, A. L. (1979). Case studies and theory development: The method of structured, focused comparison. In P. G. Lauren (Ed.), Diplomacy: New approaches in history, theory, and policy (pp. 43-68), New York: Free Press.

- Giddens, A. (1976). New Rules of Sociological Method: A Positive Critique of Interpretative Sociologies. New York: Basic Books, Inc.

- Giddens, A. (1979). Central Problems in Social Theory. London: The Macmillan Press Ltd.

- Giddens, A. (1984). The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Girishankar, N. (2001). Evaluating Public Sector Reform: Guidelines for Assessing Country-Level impact of Structural Reform and Capacity Building in the Public Sector. World Bank Operation Evaluation Department, The World Bank, Washington.

- Groot, T., & Budding, T. (2008). New public management’s current issues and future Prospects. Financial Accountability & Management, 24(1), 1-13.

- Hesse-Biber, S. N., & Leavy, P. (2006). The Practice of Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications.

- Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons. Public Administration, 69, 3-19.

- Hood, C. (1995). The new public management in the 1980’s: variations on a theme. Accounting, organizations and Society, 20(2/3), 93-109.

- Hoque, Z. (2005). Securing institutional legitimacy or organizational effectiveness? A case examining the impact of public sector reform initiatives in an Australian local authority. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 18(4), 367-382.

- Hoque, Z. (2006). Dealing with human ethical issues in research: Some advice. In Z. Hoque (Ed.), Methodological Issues in Accounting Research: Theories and Methods (pp. 487-497), UK: Spiramus Press Ltd.

- Hoque, Z., & Adams, C. (2011). The rise and use of balanced scorecard measures in Australian government departments. Financial Accountability and Management, 27, 308-334.

- Hughes, O. (1995). The new public sector management: A focus on performance. In J. Guthrie (Ed.), Making the Australian Public Sector Count in the 1990s (pp. 140-143), NSW: IIR Conferences Pty Ltd.

- Hussain, M. M., & Hoque, Z. (2002). Understanding non-financial performance measurement practices in Japanese banks: A new institutional sociology perspective. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 15(2), 162-183.

- Irvine, H., & Gaffikin, M. (2006). Methodological insights: Getting in, getting on and getting out: Reflections on a qualitative research project. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 19(1), 115-145.

- Jacobs, K. (2012). Making sense of social practice: theoretical pluralism in public sector accounting research. Financial Accountability & Management, 28(1), 1- 25.

- Jansen, E. P. (2004). Performance measurement in governmental organizations: A contingent approach to measurement and management control. Managerial Finance, 30(8), 54-68.

- Jorgensen, D. L. (1989). Participant Observation: A Methodology for Human Studies. London: Sage Publications.

- Kaplan, D., & Manners, R. (1986). Culture Theory. USA: Waveland Press Prospect Heights, IL.

- Kinchin, N. (2007). More than writing on a wall: Evaluating the role that codes of ethics play securing accountability of public sector decision-makers. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 66, 112-120.

- Layder, D. (1995). New Strategies in Social Research: An Introduction and Guide. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Llewelyn, S. (2003). Methodological issues - what counts as “theory” in qualitative management and accounting research? Introducing five levels of theorizing. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 16(4), 662-708.

- Lodh, S. C., & Gaffkin, M. J. R. (1997). Critical studies in accounting research, rationality and habermas: A methodological reflection. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 8(5), 433-474.

- Luke, B. G. (2008). Financial returns from new public management: A New Zealand perspective. Pacific Accounting Review, 20(1), 29-48.

- Macintosh, N. B., &Scapens, R. W.(1990). Structuration theory in management accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15(5), 455-477.

- Maddock, S. (2002). Making modernisation work: new narratives, change strategies and people management in the public sector. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 15(1), 13-43.

- Maor, M. (1999). The paradox of managerialism. Public Administration Review, 59(1), 5-18.

- Martin, J., & Coventry, H. (1994). Human resource management: From structural change to managerial challenge. In J. Stewart (Ed.), From Hawke to Keating- Australian Commonwealth Administration 1990-1993 (pp. 69-83), Centre for Research in Public Sector Management, University of Canberra & Royal Institute of Public Administration Australia.

- Mascarenhas, R. C. (1996). The evolution of public enterprise organization: A critique. In J. Halligan (Ed.), Public Administration Under Scrutiny: Essays in Honour of Roger Wettenhall (pp. 59-76), Centre for Research in Public Sector Management, University of Canberra and Institute of Public Administration, Australia.

- Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative Researching, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Maxwell, J. A. (2009). Designing a qualitative study. In L. Bickman and D. J. Rog (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods (pp. 214- 253), London: Sage Publications.

- Merchant, K. A., & Van der Stede, W. A. (2012). Management Control Systems. Pearson Education Limited.

- Metcalfe, L., & Richards, S. (1992). Improving Public Management. London: Sage Publications.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. London: Sage Publications.

- Modell, S. (2004). Performance measurement myths in the public sector: A research note. Financial Accountability & Management, 20(1), pp. 39-55.

- Moon, J. M. (2000). Organizational commitment revisited in new public management. Public Performance & Management Review, 24(2), 177-194.

- Moynihan, D. P. (2006). Managing for results in state government: Evaluating a decade of reform. Public Administration and Review, 66(1), 77-80.

- Mulgan, R. (2000). Comparing accountability in the public and private sectors. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 59(1), 87-97.

- Mulgan, G. & Albury, D. (2003). Innovations in the public sector. Cabinet Office Strategy Unit, United Kingdom Cabinet Office.

- OECD. (1995). Governance in Transition: Public Management Reforms in OECD Countries. OECD, Paris.

- Osborne, D., & Gaebler, T. (1992). Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit Is Transforming the Public Sector, Addison- Wesley, Reading, MA.

- Parker, L. D., & Guthrie, J. (1993). The Australian public sector in the 1990s: New accountability regimes in motion. Journal of International Accounting Auditing & Taxation, 2(1), 59-81.

- Perrons, D. (2003). The new economy and the work-life balance: Conceptual explorations and a case study of new media. Gender, Work & Organization, 10, 65-93.

- Piotrowski, S. J., & Rosenbloom, D. H. (2002). Nonmission-based values in results-oriented public management: The case of freedom of information. Public Administration Review, 62, 643-657.

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2004). Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Quattrone, P., & Hopper, T. (2001). What does organizational change mean? Speculations on a taken for granted category. Management Accounting Research, 12(4), 403-435.

- Robbins, G. (2007). Obstacles to implementation of new public management in an Irish hospital. Financial Accountability & Management, 23(1), 55-71.

- Roberts, A. S. (2000). Less government, more secrecy: reinvention and the weakening of freedom of information law. Public Administration Review, 60, 308-320.

- Schutz, A. (1967). Collected Papers. Monton.

- Simons, R. (1995). Levers of control: how managers use innovative control systems to drive strategic renewal. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts.

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The Art of Case Study Research. London: SAGE Publications.

- Tooley, S. (2001). Observations on the imposition of new public management in the New Zealand state education system. In L. R. Jones, J. Guthrie, & P. Steane (Eds.), Research in Public Policy Analysis and Management. Learning from International Public Management Reform (pp. 233-255), 11-A Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, Oxford.

- Walker, R. M., & Boyne, G. A. (2010). Introduction: determinants of performance in public organizations. Public Administration, 87(3), 433-439.

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. California: Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

Biographical notes

Anup Chowdhury, PhD, is currently working as a Professor and Chairperson of the Department of Business Administration, East West University, Bangladesh. He completed his B.Com (Hons) and M.Com in Accounting at the Faculty of Business Studies, University of Dhaka. He received his PhD from the University of Canberra, Australia on Management Control Systems. He has many years of teaching experience and has a number of publications in reputed international journals. His research interests cover a wide range of topics including; qualitative research in accounting and management control systems; accounting issues in the public sector and not for profit organizations; governance; accountability and performance measurement systems in the public sector; the role of accounting technologies in organizational change; the financial, administrative, and cultural aspects of management control systems.

Nikhil Chandra Shil, PhD, is currently working as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Business Administration, East West University, Bangladesh. He completed his BBA and MBA with concentration in Accounting Information Systems in the Department of Accounting Information Systems, Faculty of Business Studies, at the University of Dhaka. He received his PhD from the University of Dhaka on Management Accounting Practices. He is a fellow member of the Institute of Cost and Management Accountants of Bangladesh, associate member of the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA) UK, a Chartered Global Management Accountant and a Chartered Public Finance Accountant of the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy. He has a wide range of publications in reputed international journals. His research interests are; the diffusion of management accounting practices; management accounting change and innovation; behavioral management accounting; governance; tax; and public finance management.